China is the first country to retrieve rocks from the far side of the moon

June 28, 2024: This article has been updated with details about the lunar sample that were announced after the original publication date.

China brought a capsule full of lunar soil from the far side of the moon to Earth on Tuesday. This makes it a new success in an ambitious plan to explore the moon and other parts of the solar system.

The sample, retrieved by the China National Space Administration’s Chang’e-6 lander after a 53-day mission, highlights China’s growing capabilities in space and marks another victory in a series of lunar missions that began in 2007 and have been accomplished almost without fail.

“Chang’e-6 is the first mission in human history to bring back samples from the far side of the moon,” Long Xiao, a planetary geologist at China University of Geosciences, wrote in an email. “This is an important event for scientists worldwide,” he added, and “a reason to celebrate for all humanity.”

Such sentiments and the prospects of international exchanges of lunar samples highlighted hopes that China’s robotic missions to the moon and Mars will serve to advance scientific understanding of the solar system. These possibilities contrast with views in Washington and elsewhere that Tuesday’s achievement is the latest milestone in a 21st-century space race with geopolitical overtones.

In February, a privately owned American spacecraft landed on the moon. NASA is also continuing its Artemis campaign to return Americans to the lunar surface, although its next mission, a lunar flight of astronauts, has been postponed due to technical problems.

China also wants to expand its presence on the moon by sending more robots and eventually human astronauts to the moon in the coming years.

To achieve that goal, it has taken a slow and steady approach, implementing a robotic lunar exploration program that it devised decades in advance. Named after the Chinese moon goddess Chang’e (pronounced “chong-uh”), the program’s first two missions revolved around the moon to photograph and map its surface. Then came Chang’e-3, which landed on the near side of the moon in 2013 and deployed a rover, Yutu-1. This was followed in 2019 by Chang’e-4, which became the first vehicle to visit the far side of the moon and landed the Yutu-2 rover on the surface.

A year later, Chang’e-5 landed, sending nearly four pounds of lunar regolith back to Earth. The feat made China only the third country—after the United States and the Soviet Union—to pull off the complex orbital choreography of collecting a sample from the moon.

According to Yuqi Qian, a lunar geologist at the University of Hong Kong, the maneuvers of Chang’e-5 and Chang’e-6 are both tests for future Chinese manned missions to the moon. Those missions, like the Apollo missions of the 1960s and 1970s, would first land humans on the moon and then launch them from the moon.

As China strives to land astronauts on the moon, China’s long-term strategy provides scientific benefits for understanding the solar system.

The Chang’e-5 sample was younger than the lunar material collected by the Americans or Soviets in the 1960s and 1970s. It is composed mainly of basalt, or cooled lava from ancient volcanic eruptions.

Two Chinese-led research teams concluded That The basalt was about two billion years old, suggesting that volcanic activity on the Moon lasted at least a billion years longer than the time frame inferred from the U.S. Apollo and Soviet Luna samples.

Other studies of the material ruled out theories about how the moon’s interior could have heated up enough to generate volcanic activity. One research group found it that the amounts of radioactive elements in the moon’s interior, which could decay and produce heat, were not high enough to cause the eruptions. Another result ruled out water in the mantle as a potential source of interior melting leading to volcanism.

Chang’e-6 launched on May 3 with even bigger science ambitions: bringing back material from the far side of the moon. The near side of the moon is dominated by wide, dark plains where ancient lava once flowed. But the far side has fewer of those plains. It also has more craters and a thicker crust.

And because that half never faces Earth, it’s impossible to communicate directly with landers on the far side of the moon, making it difficult to reach them successfully. The Chinese space agency relied on two satellites it had previously launched into lunar orbit, Queqiao and Queqiao-2, to maintain contact with Chang’e-6 during its visit.

The spacecraft used the same technique as Chang’e-5 to reach the Moon and then return its sample to Earth.

After a few weeks in lunar orbit, Chang’e-6 descended to a site on the edge of the South Pole-Aitken Basin, the oldest and deepest impact crater on the moon. Equipped with a mechanical scoop and a drill, the lander spent two days collecting lunar rocks and dust from the moon’s environment and subsurface.

The materials were then stowed away. The mission deployed a miniature rover that took a picture of the lander with a small Chinese flag aloft. Then, on June 3, the sample bus was slung back into lunar orbit by a rocket. The materials were reunited on June 6 with a spacecraft that had remained in orbit and was preparing to return to Earth.

The sample container reentered Earth’s atmosphere at 1:41 p.m. local time, traveling at about 25,000 miles per hour. according to Xinhuaa Chinese state news agency. The parachute opened about ten kilometers above the ground.

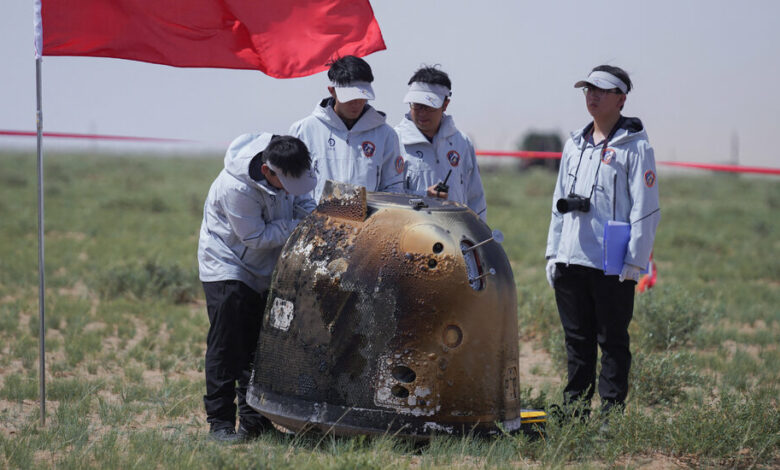

The capsule, scorched from its passage through the atmosphere, landed in the Siziwang Banner area of Inner Mongolia at 2:07 pm local time. A Chinese flag planted near the capsule fluttered in the wind as ground crews worked to recover the equipment.

The monster weighed more than four pounds, based on preliminary measurementsA mission spokesman told Xinhua on Friday that the soil appeared more viscous and lumpy, compared to material taken from the moon’s near side in the past.

Qiong Wang, deputy chief designer of Chang’e-6 at the China National Space Administration, told Xinhua earlier this week that part of the sample will be stored permanently. The rest will be distributed to researchers in China and abroad, he said.

When scientists acquire the far-side soils, they will compare the composition of the newly mined basalts with those from the near side of the moon. That could help them infer how the moon’s volcanic activity caused the two halves to evolve differently.

“New samples will inevitably lead to new discoveries,” Wei Yang, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, told Xinhua. “Chinese scientists are eagerly looking forward to the opportunity to contribute to lunar science.”

The mission team will also look for material in surrounding areas that has been blown away from their original locations by impacts from comets and asteroids. If these collisions are strong enough, they may have stripped material from the moon’s lower crust and upper mantle, Dr. Qian said. That could lead to insights into the structure and composition of the moon’s interior.

Molten rock from those impacts could also provide clues about the age of the South Pole-Aitken Basin and the epoch in which it formed, when scientists believe a barrage of asteroids and comets bombarded the inner solar system.

This period “completely changed the geological history of the moon,” said Dr. Qian, and was also “a critical time for Earth’s evolution.”

Clive Neal, a planetary geologist at the University of Notre Dame, called the goals lofty, but he’s looking forward to the discoveries that will follow the sample’s return. Referring to China’s success on the moon so far, “It’s outstanding,” he said. “More power to them.”

However, tense political relations will make it challenging for American scientists to work with Chinese researchers to study the samples on the other side of the Earth.

The Wolf Amendment, passed in 2011, prohibits NASA from using federal funds for bilateral cooperation with the Chinese government. Federal officials recently granted the space agency a waiver, allowing NASA-funded researchers to apply for access to the near-side sample obtained by Chang’e-5. But another bill passed the U.S. House of Representatives in June would ban universities with research ties to Chinese institutions did not receive funding from the US Department of Defense.

Looking ahead, China has its eyes on the moon’s south pole, where Chang’e-7 and 8 will explore the area and search for water and other resources. It hopes to send manned missions to the moon by 2030. Ultimately, China plans to build an international base at the South Pole.

NASA’s Artemis campaign also shoots at the moon’s south pole. Bill Nelson, the space agency’s administrator, previously called the parallel programs a race between the United States and China.

Many scientists reject that framing. Funds for studying the moon declined after American astronauts defeated the Soviets on the moon’s surface in 1969, said Dr. Neal. “I don’t like international space races because they are not sustainable,” he said. “A race has to be won. Once you win it, what then?”

He added: “I think it’s important to see space as something that brings us together, rather than tearing us apart.”

Several countries contributed payloads that flew on the Chang’e-6 mission, including France and Pakistan. Chinese researchers saw this as a good sign for the future.

“Moon exploration is a shared effort for all humanity,” said Dr. Xiao, adding that he hopes for more international cooperation, “especially between major spacefaring countries like China and the United States.”

Joy Dong contributed reporting from Hong Kong.