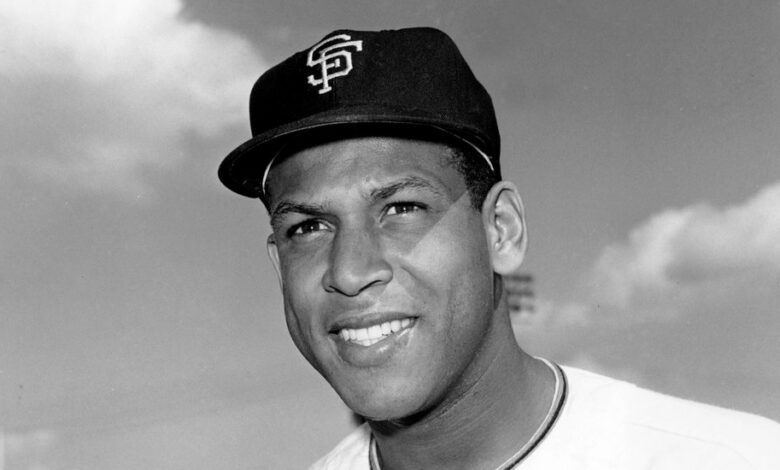

Orlando Cepeda, baseball player known as the Baby Bull, dies at 86

Orlando Cepeda, the second Puerto Rico native to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame and one of the best sluggers of his era, from the late 1950s to the early 1970s, died Friday. He was 86.

His death was announced by the San Francisco GiantsThe organization did not say where he died.

Cepeda played 17 seasons in the Major League, mainly at first base but also in the outfield and at the end of his career as a designated hitter. He hit 379 home runs, had 2,351 hits, drove in 1,365 runs and had a batting average of .297.

He was unanimously selected as the Giants’ National League Rookie of the Year in 1958, their first season in San Francisco. He was also unanimously voted the league’s most valuable player in 1967, the year he helped lead the St. Louis Cardinals to a World Series championship. He hit at least .300 in nine seasons and played in nine All-Star Games.

Cepeda’s father, Pedro, known as the Bull because of his strength, was a professional baseball player, primarily a shortstop, who was called the Babe Ruth of Puerto Rico. Orlando Cepeda, a muscular 6-foot-2-inch, 210-pound right-handed power hitter, became known as the Baby Bull.

While pitching in the Giants’ farm system, Juan Marichalthe future Hall of Famer from the Dominican Republic, was inspired by Cepeda and his fellow Latino players on the Giants.

“I would see Orlando Cepeda, Filipe Alou and Ruben Gomez on television,” Marichal once told The Associated Press. “I started learning what the big leagues were all about, and I hoped that one day I could be one of them.”

Marichal, who joined the Giants in 1960, said Cepeda was “the type of player who had no fear, the type of player you wanted behind you.”

But Cepeda’s reputation was tarnished a year after his playing days ended.

In December 1975, he was arrested in San Juan for his role in smuggling marijuana from Colombia and spent 10 months in a federal prison.

The Baseball Writers Association of America, presumably taking his prison sentence into account, snubbed him for the Hall of Fame in 15 years of voting. It wasn’t until 1999, and a vote by the Veterans Committee, Cepeda reached Cooperstown.

Cepeda was almost as revered in Puerto Rico as Roberto Clemente, the Pittsburgh Pirates right fielder and the Commonwealth’s first player. Hall of Famerwho died in a plane crash in 1972 while delivering earthquake relief supplies to Nicaragua.

But Cepeda’s drug conviction, in contrast to Clemente’s altruism, made him something of a pariah at home after his release from prison.

“When you play baseball, you have a name and money and you feel bulletproof,” Cepeda told Sports Illustrated as he was about to enter the Hall of Fame. “You forget who you are. Especially in a Latin country, they make you feel like you are God. I learned that one mistake, in two seconds, can cause a disaster that seems to last forever.”

Orlando Cepeda was born in Ponce, PR, on September 17, 1937. His father, although a baseball hero in Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the Caribbean, was a victim of the major leagues’ color barrier. He died in 1955, just before his son played his first game in the Giants’ farm system.

Cepeda hit .312 with 25 home runs for the 1958 Giants, winning Rookie of the Year honors. Three years later, he led the league in home runs, with 46, and runs batted in, with 142, as part of a slugging lineup that also included Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Felipe Alou. Cepeda helped the Giants to their first pennant in San Francisco in 1962, but they were defeated by the Yankees in the World Series.

Plagued by knee injuries, Cepeda was traded to the Cardinals for pitcher Ray Sadecki early in the 1966 season. The following year, he hit a career-high .325 and led the National League in runs batted in, with 111, and captured MVP honors. The Cardinals defeated the Boston Red Sox in the World Series.

Cepeda played on the 1968 pennant-winning Cardinals team, and later with the Atlanta Braves, the Oakland Athletics and the Red Sox. He retired in 1974 after one season with the Kansas City Royals.

He moved to Southern California in the mid-1980s and subsequently embraced Buddhism as he sought a return to baseball. “From the moment I stepped into the temple, it changed my life,” he told The AP in 1993. “It taught me to take responsibility for my actions, not to blame others.”

Cepeda returned to the San Francisco area in 1987. In 1988, he became a scout for the Giants and then joined their community relations department. Over the years he spoke to young people about drug and alcohol abuse.

But trouble arose again in May 2007, when Cepeda was stopped for speeding in Solano County, north of San Francisco. Police reported finding cocaine, marijuana and syringes in his car, but he was dismissed from the charge of possession of less than an ounce of marijuana and fined $100.

District Attorney David Paulson fired the prosecutor handling the case hours before the prosecutor was set to resign, saying the decision to drop the cocaine charge indicated Cepeda had received favorable treatment because of his celebrity status.

At the time of his death, Cepeda was still a community ambassador within the Giant organization. Information about survivors was not immediately available.

After years of being shunned in Puerto Rico, Cepeda won redemption when he was elected to the Hall of Fame. The Puerto Rican government brought him back for a parade in his honor. It began at the San Juan airport, where he had been arrested 24 years earlier, and wound through Old San Juan along streets filled with crowds of people.

The Giants retired Cepeda’s number 30 two weeks before his induction into the Hall of Fame. In September 2008, they honored him with a bronze statue outside their stadium, AT&T Park (now Oracle Park). It stands next to statues honoring Mays, McCovey, Marichal and pitcher Gaylord Perry. After all his trials, Cepeda was extremely satisfied.

“When things like this happen to you,” he told The San Francisco Chronicle at the unveiling of his statue, “I say to myself, ‘Orlando, you are a very lucky person.’”