Residents of America’s cancer-cursed state demand answers as rates of disease mysteriously soar

Across Iowa, people have known for a long time what data is only now beginning to confirm — cancer incidence in the state is outstandingly high.

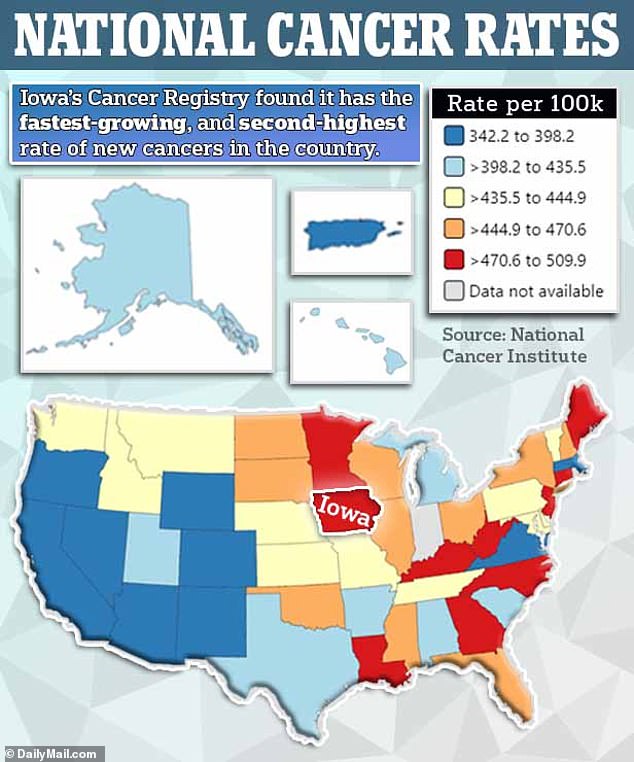

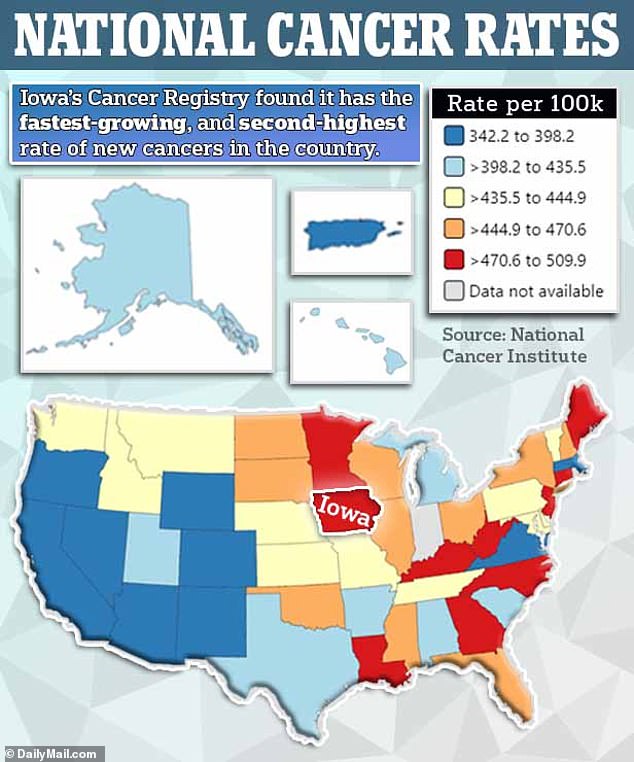

Iowa became the focus of national attention earlier this year when data showed it had the fastest growing rate of new cancers of any state in America.

That’s more than the Rust Belt states, where lifelong factory work, smoking rates and lack of healthcare puts locals at a higher risk for developing the disease. And more than southern states where rates of obesity, alcohol use and poverty make them more prone to the disease.

A complex web of factors is thought to be at play – Iowa is a farming powerhouse and uses more potentially carcinogenic pesticides than anywhere else. It’s also sitting on a hotbed of radioactive gas, called radon, which can leech into homes undetected and cause lung cancer.

Residents are unwilling to accept being sickened by their home and are demanding state leaders do something about the crisis.

The Dunns raised their three boys in a suburb of Davenport, Iowa, which sits near the eastern border of the state

Sharon Kendall-Dunn, 56, and Dave Dunn, 63, live in the eastern part of the state, in a suburban town called Davenport, Iowa.

They’ve lived in the area their whole lives and raised their three sons, who are all in their twenties, there.

Mr Dunn was diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in early 2014. Ms Kendall-Dunn was diagnosed with a rare form of bone marrow cancer, called chronic myeloid leukemia, in November 2022.

As with many cancer cases, there was no clear cause of the disease for the Dunns – they barely drink, they don’t smoke and are active people.

Mr Dunn has a family history of Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but oncologists don’t usually consider it a disease that’s heritable.

When Mr Dunn asked his doctor what could’ve caused his disease, the doctor said simply: ‘You live in Iowa.’

In response, the Dunn’s have become hypervigilant about testing the water they consume. They are particularly concerned about the presence of agricultural chemicals – pesticides, herbicides and byproducts of fertilizer – in their water.

They want more efforts by their city, county and state to test, report and treat their water for chemicals like pesticides, herbicides, and byproducts of fertilizers called nitrates.

They also want national standards for the amount of these chemicals allowed into the water supply to be re-evaluated.

They are among many people who DailyMail.com spoke to about the 2024 Cancer in Iowa report, who wanted more attention paid to the state’s use of agricultural chemicals.

The report found there would be 486 new cancers per 100,000 people in Iowa higher than the US rate of 444 new cases per 100,000. It’s estimated 21,000 new cancers will be diagnosed in 2024 – and 6,100 people will die.

The Iowa Cancer Registry, which ran the report, focuses on a different cancer risk factor each year. This year, they highlighted alcohol as a contributor to the problem – noting that Iowa had the fourth highest binge drinking rate in the nation in 2022.

This led to a widespread sentiment that public officials were pinning the blame for the cancer crisis on alcohol alone. Officials said this was a misunderstanding.

Linus Solberg has lived his entire life in Iowa, growing up on farms. He’s lost a dozen neighbors to cancer

Palo Alto county, nestled in the northwestern Iowa, is largely rural and agricultural. It’s home to corn, soy and pig farms as well as ethanol manufacturing plants and wind farms

The Iowa Cancer Registry ran a community profile specifically for Palo Alto County in hopes of explaining why its cancer trends were outsized multiple years in a row, but health officials said it’s begun leveling off

Linus Solberg, a Palo Alto County supervisor and farmer, told DailyMail.com he was frustrated to see people blaming alcohol for the cancer rates in the state, because none of the dozen cancer victims he knew drank regularly.

Mr Solberg lost his wife to lung cancer ten years ago. She didn’t smoke, didn’t drink and didn’t have a family history of lung cancer.

He lost his mom to ovarian cancer when she was in her sixties.

He knows of at least a dozen neighbors who have died from multiple types of cancer – including lung and breast.

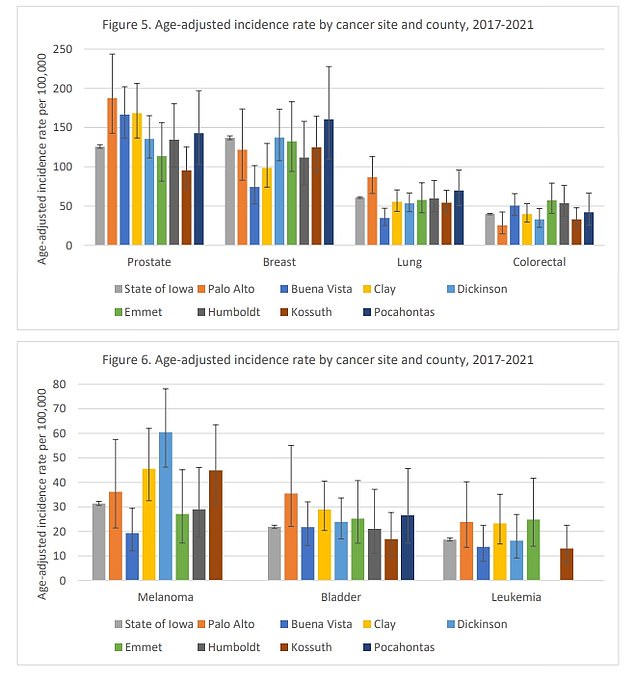

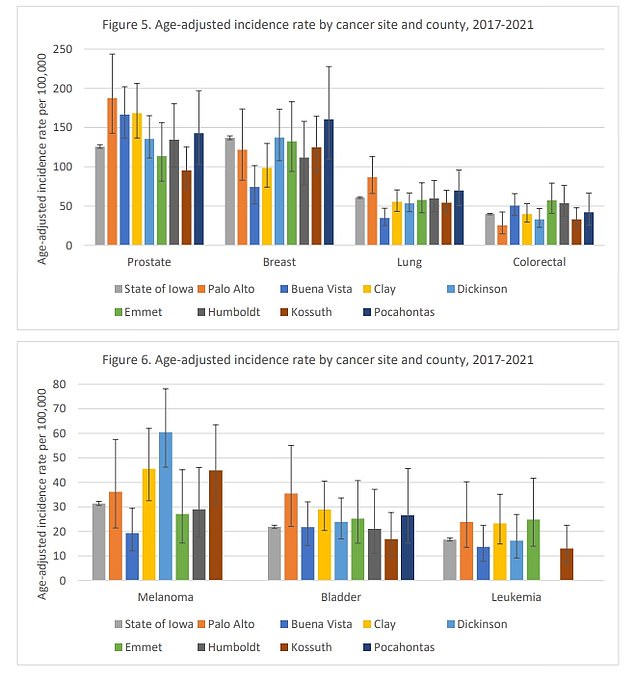

The most common types of cancer in the state are lung, breast, prostate and melanoma.

In Palo Alto county, prostate, lung, bladder, blood and skin cancers outpace state averages, according to a community profile the Iowa Cancer Registry ran in 2024.

Until recently, the county, home to roughly 8,700 people in Northern Iowa, had the highest cancer rate in the state and the second highest of any county across the US.

Mr Solberg has lived here his whole life and said cancer wasn’t as prevalent when he was younger.

It’s a rural county – as of the 2017 census, 1,213 people made their living growing corn, soybeans or pigs.

He suspects the agricultural nature of his county could have something to do with the cancer rate, though he doesn’t think it’s the corn alone.

Radon is a naturally-occurring radioactive gas that gets released as bedrock weathers over time. It’s colorless, odorless and virtually undetectable, and can seep into homes, affecting the lungs of residents who breathe it in.

It’s the number one cause of lung cancer in non-smokers – and in Iowa, radon levels are six times higher than the national average, affecting an estimated 72 percent of homes.

Mr Solberg told DailyMail.com he believes a combination of radon, waste from farms and agricultural chemicals is behind the cancer epidemic.

He said: ‘We have radon in our houses. We have arsenic in our wells. And we use a lot of chemicals on our crops.’

The trend is clear, he said, and it’s good that people have brought attention to it, but there’s been little done about it.

‘What has me the most upset probably, is that nobody’s actually trying to do anything about it,’ he said.

Previous public health efforts in the area – like a push to use tax dollars to expand mental health services during the pandemic – have been successful in the county.

As he see’s it, there have been little efforts from the government to address the cancer issues. He wants more research to be performed in the area to get to the bottom of it.

But Mr Solberg said he’s willing to take time and money to fund and participate in research and public health initiatives in the county, and suspects his neighbors, who’ve also lost loved ones to cancer, will have a desire to do the same.

Sarah Strohman, RN, BSN, the director of Community Health at Palo Alto County Health System told DailyMail.com said that the Iowa Cancer Registry, which is funded through the National Cancer Institute, has dispatched specialists to study the area.

In July, the organization released a report that said that cancer rates in Palo Alto had begun to level off in all areas except for lung – suggesting a need for greater awareness about radon testing.

Downtown Davenport, Iowa was empty because a series of floods had passed through earlier that week

Sharon Kendall-Dunn and David Dunn live in Davenport, near the Mississippi river and the state border with Iowa. There was substantial flooding in the area in 2024

About 290 miles away from Palo Alto County, in Davenport, the Dunn’s are dealing with the harrowing effects of cancer daily.

Mr Dunn had to undergo multiple rounds of chemotherapy, experimental drugs, and multiple stem cell transplants, which led to an excruciating condition known as graft versus host disease.

This is a condition where the implanted stem cells begin attacking the person they were transplanted into. It can attack any part of the body, but common symptoms include rash, nausea, jaundice, diarrhea, fatigue, muscle weakness and hair loss.

As a result of the many treatments, Mr Dunn has lost about 70 percent of his kidney function.

He estimates he’s taken at least 160 trips to the Mayo Clinic, which is about 230 miles away, for treatment in the past ten years.

The ongoing care would cost cost the couple roughly $400,000 annually without insurance, but Mr Dunn has been able to stave off the majority of those costs with his company’s plan.

Ms Kendall-Dunn takes chemotherapy pills designed to fight her specific mutation every day. They’re effective, but they’ve deprived her of her energy and cause severe stomach pain and nausea.

Mr Dunn has finally gone into remission but Ms Kendall-Dunn never will. She said her disease is managed by her medication.

In the years that they’ve fought cancer together, the couple has had a long time to consider what could’ve contributed to their diagnoses. They’ve come to believe the answer lies in their environment.

Pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and byproducts of fertilizer called nitrates, can get into water supply after being applied to fields to help produce an even crop yield.

Downstream effects of agricultural chemicals have been seen as far away as the Gulf of Mexico – leading to a wave of environmental efforts in the past decades.

There are many different kinds of pesticides approved by use for the Environmental Protection Agency – they maintain that all have been through a strict approval process.

Some of these bug, weed or fungus killers have been linked by scientists to cancer, particularly to blood and lymph cancers, like Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Some of these chemicals are banned in other countries.

The health effects of nitrates, which are byproducts of fertilizers and manure, are a bit more widely accepted.

Nitrates have been linked to colon, kidney, stomach, thyroid and ovarian cancer, and can also cause fatal disease in newborns, according to the National Cancer Institute.

There are ways to treat water for nitrates and pesticides, but in order to treat the water for those substances, one first has to test the water and determine that those chemicals are in there.

Since Mr Dunn’s diagnosis, the couple has moved to put filters on their shower, garden hose and sinks, and have bought the same equipment for their sons’ homes.

They only drink water that has been filtered, and they test their water for nitrates semi-regularly.

Ms Kendall-Dunn told DailyMail.com: ‘I think the public has a right to clean water. And I’m not saying it is the water. But I’m also saying not saying it’s not. I don’t know where this chemical exposure came from.’

They want more efforts by their city, county and state to test, report and treat their water for things like nitrates and pesticides.

In addition, they want official guidelines for the amount of nitrates allowed in water, which is currently 10 milligrams per liter of water, to be re-evaluated.

Wayne Brimeyer initially went to the doctor because he was experiencing stomach pain after testing for his second-degree black belt in Taekwondo

Mr Brimeyer lives in a rural part of Illinois but works in Iowa every day. The Mississippi river (pictured) marks the border between the states, which Mr Brimeyer crosses to get to work

Through the years, the Dunns have taken to leaning on organizations like Gildas club for community support.

Wayne Brimeyer, 55, is a member of Gilda’s Club who was diagnosed with incurable stage four pancreatic cancer in June 2021.

He lives with his wife and three children just over the bridge from Davenport, in a small rural town in Illinois.

He considers himself a ‘country person’, but works in town in Iowa for a welding supply company and has worked there for years.

He doesn’t drink the water in town, because there are too many chemicals and it tastes bad, and instead opts to drink water from a private well on his property.

Since his diagnosis in 2021, he’s been undergoing chemo through an IV every two weeks- though he recently had to discontinue the treatment because of some new developments.

He suffers with intense fatigue and nausea as a result and has lost feeling in the bottoms of his feet – a common side effect of chemotherapy drugs.

In addition, he had surgery to remove two thirds of his pancreas – putting him at risk for developing diabetes.

But what struck him more than anything in his cancer diagnosis is how alone and scared he felt. The resulting pain and depression were nearly unbearable.

When he found Gilda’s Club, the burden was suddenly lifted.

‘There is a relationship between cancer people, a connection, that someone without cancer really doesn’t get,’ he said.

Because he can’t change the fact that he has cancer, all he wants to do is enjoy what time he has left, and make his home a better place for other people dealing with the disease by raising awareness for groups like Gilda’s club.

Until then, he said, ‘Will the cancer kill me? Maybe someday, but not today. Today I’ve got cribbage club with my kids.