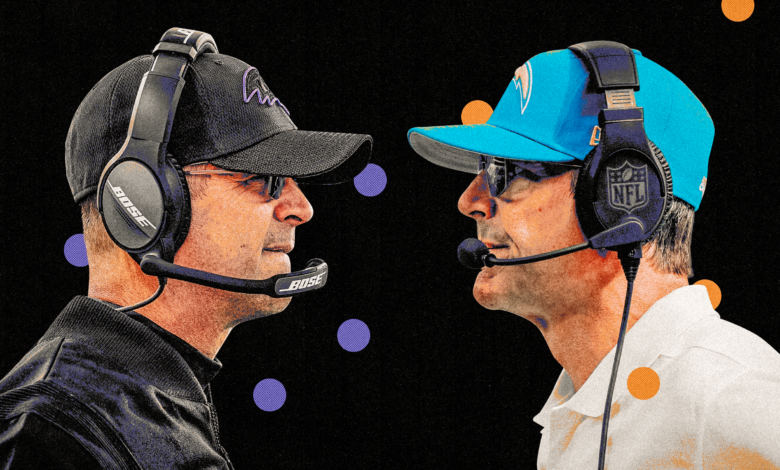

After a decade apart, John and Jim Harbaugh resume NFL’s most fascinating rivalry

On Nov. 25, the brothers Harbaugh will meet in the middle of a football field with squared shoulders and clenched jaws. It will be the first time Jim and John have opposed one another in 12 years.

That doesn’t include four hours of floating table tennis in a pool on a recent vacation — diving for shots, intentionally making waves and splashing the table for an advantage. Or the Thanksgiving gathering when they staged a “wives’ wingspan competition,” using a tape measure to determine which of the family wives had the best wingspan-to-height ratio. It also doesn’t include their fishing competitions. Who would get the first bite? Who would reel in the biggest fish? Who would catch the most in an hour?

When they last met on a football field, John was so out of sorts about trying to best his brother in Super Bowl XLVII that he came out for pregame warmups without his ballcap. He always wears one at games, as does Jim, because their father, Jack, did. Without it, John felt lost.

He walked across the field and stood near Jim, waiting for a nod or smile, but was ignored. So John talked to 49ers kicker David Akers, whom he had coached in Philadelphia.

“You trying to get in my kicker’s head?” Jim shouted, not very fraternally.

“Well, he’ll talk to me,” John said. “You won’t talk to me.”

They came together and stood near the middle of the field at the center of the NFL universe, the best of friends and fiercest of foes entirely unsure of how to act, and managed a few words that conveyed nothing.

Then they went at, with John’s Baltimore Ravens taking a 28-6 lead in the third quarter before Jim’s San Francisco 49ers scored 26 of the next 29 points to get within three with less than three minutes remaining. John’s Ravens held on to win 34-31, and the emotions of the head coaches were conflicted in a way they never were before.

The wrinkles and wisdom have deepened since then, but neither has stopped feeling the elation of that greatest victory or the deflation of that most devastating defeat. That game and that season belonged to the Harbaughs.

Now, with John in his 17th season leading the Ravens and Jim coaching the Los Angeles Chargers after nine years at the University of Michigan and fresh off a national championship, their collective forces will undoubtedly shake and shape the NFL once more. And as they stand in the other’s way for command of the AFC, the sport has no more fascinating rivalry.

The last time the Harbaugh brothers faced each other in the NFL, John’s Ravens edged Jim’s 49ers to win Super Bowl XLVII. (Ezra Shaw / Getty Images)

As children, they shared a bedroom. But it was separated by a line of adhesive tape on the floor. John, 15 months older, told Jim to stay on his side.

John was the measuring stick for Jim. He wanted to be — no, needed to be — better than John at everything. It was John’s approval that mattered most.

The big brother was magnanimous, always including Jim in games with his friends. Whenever John was a team captain, he always picked Jim for his side. They were usually a package deal when it came to organized football, baseball and hockey.

Though John was the big brother, he wasn’t always the bigger brother. Sometimes, Jim’s growth spurts evened things up or made Jim the larger of the two. At 6-foot-3, Jim ended up three inches taller than John.

“He was always chasing the pencil mark on the doorframe, so he drank a gallon of milk a day to help his bones grow,” John says. “He thinks he’s taller than me because he wanted to be.”

Being bigger mattered when boys would be boys. During the years John had a size advantage, Jim developed a wrestling technique he called the “crab.”

“When it all went bad and I knew he was the stronger guy, I’d get on my back and stick my legs up and block him with my legs, then block his hands with my hands,” Jim says. “And he’d get mad at me for getting into the crab.”

But when Jim got bigger, John used the crab against him.

“Having a younger brother bigger than you in a wrestling match, that’s tough,” John says. “You gotta fight for your life. You can’t let him pin you down.”

As the quarterback at Michigan, Jim set the school’s passing record and was named Big Ten Player of the Year. The Bears chose him in the first round of the 1987 draft, and he played 15 NFL seasons, leading the league in passer rating one season, winning Comeback Player of the Year another and earning a place in the Colts Ring of Honor. He had no truer fan than John, who makes a case for his brother as the most underrated quarterback in NFL history.

GO DEEPER

Jim Harbaugh on the Michigan title and moving to the Chargers

John had designs on changing the world as a politician when he was a defensive back at Miami of Ohio. Then, spending a year as a volunteer assistant on his father’s coaching staff at Western Michigan helped him discover another way to impact lives. While Jim was cashing NFL checks, John scraped by as a coaching grunt at five colleges, catching his break when Ray Rhodes hired him to lead the special teams with the Eagles.

When Jim retired from playing and expressed an interest in coaching, John recommended him to Mike Lombardi, whom he had worked with in Philadelphia and had become a trusted adviser to Al Davis in Oakland. Jim didn’t know how to turn on a computer, but he became a Raiders offensive assistant.

Jim was named head coach at Stanford five years later and offered his defensive coordinator job to John. But John decided to stay in Philadelphia to coach defensive backs under first-year head coach Andy Reid. The following year, John became the head coach of the Ravens.

The way they became head coaches is reflected in their styles.

“Jim was a quarterback, so he brings a quarterback approach to things,” says quarterback Josh Johnson, who played for Jim at the University of San Diego, was on Jim’s 49ers team twice and is on his second stint with John’s Ravens. “John, he’s always been a coach, and he takes more of a head coach approach.”

While they took different paths, they ended up in the same place philosophically.

“I think that we see the game almost exactly the same way,” John says.

Jim’s son, Jay, has worked for both and says the transition from John’s Ravens to Jim’s Michigan team was seamless.

“They both take a common-sense approach to football — block, tackle, run the ball, stop the run, turnovers, emphasis on fundamentals and technique,” says Jay, now the special teams coach for the Seahawks. “And it’s all about what’s best for the team and not any particular player, coach or unit.”

Jay Harbaugh, left, Jim’s son, has followed his dad, Uncle John and Grandpa Jack into coaching. (Courtesy of Ingrid Harbaugh)

The Harbaughs understand toughness as the elemental quality in the sport they teach. You can see it in their game tape. And you can see it in their interactions. Neither is conflict-averse.

Jim had to be separated from then-Lions coach Jim Schwartz during a 2011 postgame “handshake.” Before a game against the Titans in 2020, John marched out to midfield to chase Titans cornerback Malcolm Butler off the Ravens logo.

“As a player, you appreciate that because they are ready to go to battle with you,” Johnson says.

Jack, a 41-year coaching veteran, taught them that confrontation, when channeled correctly, can be productive. When they stepped out of line as kids, they knew their father would not look the other way. They called his outbursts “50-megatonners,” which sometimes resulted in Jack knocking their foreheads together.

“You know, get the foreheads to boink,” John says.

John, 61, and Jim, 60, idolize Jack. He and their mother, Jackie, will commemorate 63 years of marriage on Nov. 25 — the day the Ravens play the Chargers. Jim and John hold firm to lessons from their childhood dinner table, assured in their hearts they are life’s truths. There, they learned how to “attack each day with an enthusiasm unknown to mankind” — Jack’s favorite phrase — and how to attack an odd defensive front or a quarterback with wheels.

At 85, Jack still watches tapes of his sons’ games and practices. He counsels both with considerable pride. His sons are undeniably the most accomplished coaching brothers in the history of their sport. John’s 160 victories are 20th most all time. Jim’s .695 NFL winning percentage is the fifth-highest ever. Their combined record as head coaches, including Jim’s years at the University of San Diego, Stanford and Michigan, is 351-170-1, a winning percentage of .672.

The family’s shared wisdom has been pooled in a new endeavor that could spread the Harbaugh gospel for generations. The Harbaugh Coaching Academy — which includes contributions from former college basketball coach Tom Crean, the husband of John and Jim’s sister Joani — seeks to develop coaches, educators and parents. In one video, John and former NFL quarterback Matt Hasselbeck discuss what “sports parents” should talk about with their kids after games. In another, traumatic brain injury expert Dr. Geoffrey Ling weighs in on when kids should start playing football.

Free, daily NFL updates direct to your inbox.

Free, daily NFL updates direct to your inbox.

The family’s footprint on the game is enormous and keeps expanding. New Seahawks head coach Mike Macdonald is a disciple of both, having served as the defensive coordinator for John with the Ravens and Jim at Michigan. Five of Jim’s Michigan assistants are college head coaches, including successor Sherrone Moore at Michigan and Jedd Fisch at Washington.

When Jim became head coach of the Chargers, he hired Greg Roman as his offensive coordinator. Roman was John’s offensive coordinator for five years after working for Jim in San Francisco. Others who have answered to both Harbaughs include Chargers defensive coordinator Jesse Minter, Chargers run game coordinator Andy Bischoff, Chargers senior offensive assistant Marc Trestman, Ravens running backs coach Willie Taggart, Ravens secondary coach Doug Mallory and Eagles defensive coordinator Vic Fangio.

They have advised one another about many aspects of the game. When Jim was the coach of the 49ers, he gave John intel on NFC West opponents before the Ravens prepared to play them. John reciprocated with information on AFC North teams.

They have compared notes on how to most effectively deliver a message in a press conference and how to get a point across in a meeting with assistants. Jim has asked John to look at a speech, and John suggested edits. John leans on Jim for motivational tips. When John has questions about what an offensive opponent sees, he may ask Jim.

“There is nobody’s recommendation that I trust more than my brother’s, nobody even at the same level,” says Jim, who wanted former Ravens player personnel director Joe Hortiz as his general manager after hearing John’s sales pitch. “It’s not because he’s my brother, but because he is one of the best coaches in the history of football.”

“They bounce a lot of ideas off one another,” Jay says. “It’s kind of neat to see the way they sharpen each other.”

John was a sounding board for Jim last year when the NCAA, Big Ten and his own university held him responsible for recruiting violations and stealing signs. John called what happened pure comedy and supported Jim publicly as well as privately.

“He told us what was going on behind the scenes,” John says. “It was interesting to learn the details and the deals that were made between the NCAA, the Big Ten and Michigan at Jim’s expense.”

The Harbaughs celebrate Michigan’s national championship — brother-in-law Tom Crean, left, Jim, John and sister Joani. (Courtesy of Ingrid Harbaugh)

Jim was suspended for six of Michigan’s 15 games, including a November game at Maryland, which he and his wife, Sarah, watched with John and Ingrid at their suburban Baltimore house.

After the Michigan victory, Jim left to meet the team at the airport for the flight home while John and Ingrid went to mass. During the service, John received a text. Did he know where Jim’s phone was? John and Ingrid left the church, found Jim’s phone on their stairs and dashed to the airport, where security awaited. Once Jim had it, he called John and put him on speaker so he could deliver a victory speech.

“It was a very Jim thing to do,” John says.

Now that they are more direct competitors, they are more measured about the football information they share. They say they don’t mind because there are many other topics they can connect about.

They text and talk on the phone regularly, but their primary source of communication is a Wordle group chat. Seventeen Harbaughs compete in the game daily, along with Connections and the Mini Crossword. In the chat, they share what’s happening in their lives and sometimes post photos.

While Jim says brothers-in-law John Feuerborn and Tom Crean are the best at word games, he gushes about John as a leader, communicator and strategist.

“Nobody could ever ask for a better brother in every way,” he says. “I sometimes think about if he were a Bible character, which one he would be? He’d be up there with some of the greats in my mind.”

Both are transparently Christian. John has quoted scripture in postgame news conferences. Jim, who has served as a missionary, spoke at the March For Life in Washington, D.C., in January and said his Michigan team last year was on a spiritual mission after 70 of his players were baptized.

“If someone says ‘Allahu Akbar,’ you know, ‘God is great,’ that’s fine with us,” John says. “But if we offend you by saying the word ‘Jesus’ or talking about our faith, I’ll live with that and so will Jim.”

Jim likes to say, “Just be yourself.” John says Jim embraces that mindset more than anyone he’s ever known.

“They both have tremendous conviction in who they are and a very, very low regard for other people’s opinions of them,” Jay says. “They have no interest in looking good or looking smart, even though they are both like geniuses.”

GO DEEPER

John Harbaugh ‘heartbroken’ Ravens missed opportunity to play in this season’s Super Bowl

Jim is known as the quirky brother. He takes cold plunges wearing his signature khaki pants, calls SpongeBob SquarePants a hero, and, citing inspiration from the 1970s TV series “The Rockford Files,” lived in an RV for four months after being named head coach of the Chargers. John says Jim is misunderstood. He also says his own quirkiness may be underrated.

John’s wife and daughter call him “Shelldon,” because on beach visits, he collects every shell he can find. “I’m like, ‘What are we going to do with them?’” Ingrid says. “He’ll say, ‘Put them around the house.’ I’m like, ‘Oh my God, there are so many shells!’”

The uninitiated might presume both are humorless, as serious as Black Monday. The truth is John and Jim laugh a lot together. Each finds the other hilarious.

But when the Ravens play the Chargers, no one expects any jocularity.

John, left with wife Ingrid, and John, right with wife Sarah, make each other laugh, just not on the field. (Courtesy of Ingrid Harbaugh)

After the final snap of Super Bowl LXVII, there was no Gatorade bath or ride off the field on the shoulders of his players for John. Everyone knew he had something he needed to do.

Appropriately solemn, he found Jim at midfield, shook his hand and went in for the hug. Jim, still feeling the heat of the battle, stiffened his arm so John couldn’t get close to him.

“There will be no hug,” a stern Jim declared.

No hug?

“It was the Winston Churchill in me,” Jim says now, perhaps with a tinge of regret. “Always defiant in defeat.”

John settled for a half-hug/shoulder bump.

They stood there in a haze with purple-and-gold confetti swirling, photographers swarming and snapping and a celebratory anthem booming. There was just one thing both were sure of and always have been, but it needed to be said in the moment.

“Love you, Jim,” John said.

“Love you, too,” said Jim.

The story of the greatest players in NFL history. In 100 riveting profiles, top football writers justify their selections and uncover the history of the NFL in the process.

The story of the greatest players in NFL history.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; photos: Robin Alam / Icon Sportswire, Jevone Moore / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)