India

Friendly, articulate and pragmatic communist | India News – Times of India

Sitaram Jechury, who died on Thursday, was a committed communist in party politics, but in political practice — to use a term widely used by Marxist pundits — he preferred pragmatism to dogma. And like many pragmatic politicians of his generation, he was courteous and friendly, qualities that did not depend on the side of the aisle to which his interlocutor belonged.

He was among the few CPM leaders who did not think too much ideologically about the question of whether the party should ally with Congress, which was earlier seen as the main opponent of the communists, to take on the BJP when it became a ruling party under Vajpayee.

During the 2024 campaign, he had insisted that the Modi-led BJP should contest state contests through alliances. An analysis that is partly borne out by the results. Interestingly, CPM’s ideological purists still do not formally acknowledge the party’s alliance with the Congress, let alone that CPM is part of INDIA block.

During the 2024 campaign, he had insisted that the Modi-led BJP should contest state contests through alliances. An analysis that is partly borne out by the results. Interestingly, CPM’s ideological purists still do not formally acknowledge the party’s alliance with the Congress, let alone that CPM is part of INDIA block.

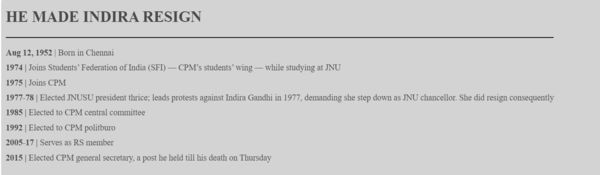

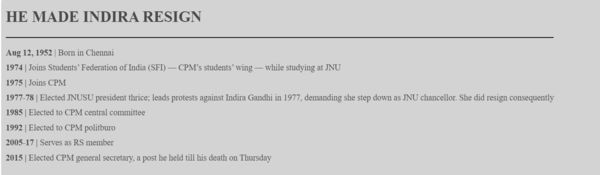

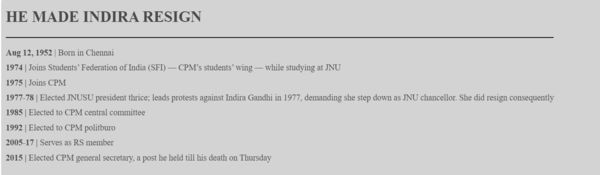

That Yechury, as a student politician, had forced Indira Gandhi to resign as chancellor of JNU made his later pragmatism all the more striking. His distancing from the Naxalite movement in the 1970s, because that offshoot of Marxist politics espoused loyalty to the Chinese communists, was another indication of his practical political sense. As he had said in 2014, when Modi first came to power: “The circumstances have changed, so our calculus and tuning will change accordingly.”

If we compare his pragmatism with that other practical communist, Harkishen Singh Surjeet, an astute alliance builder, it is noticeable that the difference in the success rate of the two can largely be explained by the fact that the CPM was in a more politically dominant position during Surjeet’s heyday.

Yechury’s easygoing nature was not a later political makeover. Even as a student activist, he was not known for being overbearing or loudly declaratory. Engaging in debates was his style and witty one-liners were his rhetorical hallmark. Many politicians, including communists, are given to name-calling. Yechury was never one of them. The other striking feature was that, unlike many other Marxists, he avoided jargon. Again, unlike doctrinaire Marxists, he was always interested not just in class but also in social groups and religion. He understood the latter to be valuable in understanding Indian society.

Telugu was his mother tongue. In the party forum and meetings he preferred English, as he found political formulations easier in that language. But he delivered public speeches in Hindi. During his two terms in the Rajya Sabha of Bengal he tried to speak in Bengali while talking to Bengali journalists.

Born in a Telugu Brahmin family, Yechury refused to wear the sacred thread and chant slokas. He said he was the first communist in his family. But he did not deny the philosophical debates embedded in the ancient religious texts. An open mind that later helped him debate with the Hindu Right.

Those who knew him well said that one of Yechury’s defining qualities as a politician was that he was more interested in finding common ground than differences between parties and groups. These qualities served him well in Parliament, where his articulateness stood out when the overall quality of parliamentary interventions deteriorated. When he ended his Rajya Sabha term in 2017, the tribute from Samajwadi Party MP Ram Gopal Yadav stood out. But he was not the only MP who felt that the House would miss Yechury.

Of course, as the Left’s electoral footprint shrank, the national political significance of CPM leaders, including Yechury, also declined. The peak was between 2004 and 2008 — from the time UPA-1 was formed to the time CPM withdrew support from the Manmohan Singh government over the Indo-US nuclear deal.

It is rare for Indian politicians, including communists, to introspect publicly. But Yechury proved an exception when, after UPA-2 took office, he admitted that his party had failed to explain its stand on the nuclear deal to voters, who had given a Congress-led coalition a healthy victory. He was perhaps the only politburo member to do so.

The loss of Bengal to TMC was a blow to CPM and its leaders from which they have not recovered. Yechury, along with other CPM leaders, rarely made national headlines.

However, his international communist connections made him very relevant when the UPA government in 2009 sought his help in reaching out to Nepal’s Maoist leader Prachanda, who later became prime minister.

Yechury’s last public message came on the day he was shifted from the ICU to a general bed at AIIMS, Delhi. The recorded message was his tribute to another communist stalwart, former Bengal Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, who passed away recently.

Yechury faced a deeply personal tragedy when he fell ill. He lost his son Ashish to Covid in 2021. He was never quite the same again, those close to him said. The father in him was destitute. But it says much about his capabilities as a politician that the pragmatic communist in him persevered.

He was among the few CPM leaders who did not think too much ideologically about the question of whether the party should ally with Congress, which was earlier seen as the main opponent of the communists, to take on the BJP when it became a ruling party under Vajpayee.

That Yechury, as a student politician, had forced Indira Gandhi to resign as chancellor of JNU made his later pragmatism all the more striking. His distancing from the Naxalite movement in the 1970s, because that offshoot of Marxist politics espoused loyalty to the Chinese communists, was another indication of his practical political sense. As he had said in 2014, when Modi first came to power: “The circumstances have changed, so our calculus and tuning will change accordingly.”

If we compare his pragmatism with that other practical communist, Harkishen Singh Surjeet, an astute alliance builder, it is noticeable that the difference in the success rate of the two can largely be explained by the fact that the CPM was in a more politically dominant position during Surjeet’s heyday.

Yechury’s easygoing nature was not a later political makeover. Even as a student activist, he was not known for being overbearing or loudly declaratory. Engaging in debates was his style and witty one-liners were his rhetorical hallmark. Many politicians, including communists, are given to name-calling. Yechury was never one of them. The other striking feature was that, unlike many other Marxists, he avoided jargon. Again, unlike doctrinaire Marxists, he was always interested not just in class but also in social groups and religion. He understood the latter to be valuable in understanding Indian society.

Telugu was his mother tongue. In the party forum and meetings he preferred English, as he found political formulations easier in that language. But he delivered public speeches in Hindi. During his two terms in the Rajya Sabha of Bengal he tried to speak in Bengali while talking to Bengali journalists.

Born in a Telugu Brahmin family, Yechury refused to wear the sacred thread and chant slokas. He said he was the first communist in his family. But he did not deny the philosophical debates embedded in the ancient religious texts. An open mind that later helped him debate with the Hindu Right.

Those who knew him well said that one of Yechury’s defining qualities as a politician was that he was more interested in finding common ground than differences between parties and groups. These qualities served him well in Parliament, where his articulateness stood out when the overall quality of parliamentary interventions deteriorated. When he ended his Rajya Sabha term in 2017, the tribute from Samajwadi Party MP Ram Gopal Yadav stood out. But he was not the only MP who felt that the House would miss Yechury.

Of course, as the Left’s electoral footprint shrank, the national political significance of CPM leaders, including Yechury, also declined. The peak was between 2004 and 2008 — from the time UPA-1 was formed to the time CPM withdrew support from the Manmohan Singh government over the Indo-US nuclear deal.

It is rare for Indian politicians, including communists, to introspect publicly. But Yechury proved an exception when, after UPA-2 took office, he admitted that his party had failed to explain its stand on the nuclear deal to voters, who had given a Congress-led coalition a healthy victory. He was perhaps the only politburo member to do so.

The loss of Bengal to TMC was a blow to CPM and its leaders from which they have not recovered. Yechury, along with other CPM leaders, rarely made national headlines.

However, his international communist connections made him very relevant when the UPA government in 2009 sought his help in reaching out to Nepal’s Maoist leader Prachanda, who later became prime minister.

Yechury’s last public message came on the day he was shifted from the ICU to a general bed at AIIMS, Delhi. The recorded message was his tribute to another communist stalwart, former Bengal Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, who passed away recently.

Yechury faced a deeply personal tragedy when he fell ill. He lost his son Ashish to Covid in 2021. He was never quite the same again, those close to him said. The father in him was destitute. But it says much about his capabilities as a politician that the pragmatic communist in him persevered.