Children born from sperm or egg donors have ‘trust issues’ and are at greater risk of ADHD if they are not told about their medical history, research finds

A study has found that children conceived using donated eggs or sperm are more likely to experience “trust issues” and “identity issues” than non-donor children.

Researchers from King’s College London, who studied data from 4,666 people conceived from donated genetic material, said the problems arose from secrecy and anonymity surrounding parentage.

However, they found that these individuals fared better when they were informed of their origins at an early age.

Since 1991, when donor child registration began, over 70,000 people have been born to donor babies in the UK. A significant number of them were born before that date.

However, little is known about the long-term psychological challenges children face during childhood.

Since 1991, when registration began, over 70,000 donor-transmitted children have been born in the UK, with a significant unknown number born before that date.

However, new research from King’s shows that adults conceived via an egg or sperm donor may be troubled by the secrets of their origins.

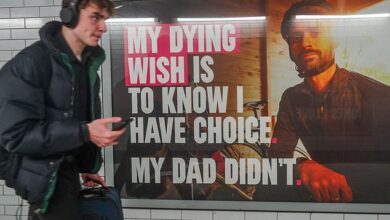

Some people only find out after they have taken a DNA or family tree test. This can reveal that they have multiple half-siblings from the same donor.

In some rare and shocking cases, couples have discovered that they are actually related.

Under UK law, anyone conceived from donated genetic material has the right to find out more about their donor, including their name and address at the time of donation, at the age of 18.

However, this only came into effect in 2005, so people conceived before then have no guarantee of this information.

And even though this legislation now exists, the decision to tell a person conceived through donation the truth about his or her origins lies entirely with the parents raising him or her.

The researchers’ study, published in the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecologylooked at 50 studies on the mental well-being of both donor children and adults.

In total, 4,666 people were donor-conceived, mainly from high-income, English-speaking countries.

Research has shown that most studies show that donor-conceived children have higher or equal scores on measures of well-being, self-esteem, and relationship warmth compared to non-donor-conceived children.

According to the study’s lead author, Professor Susan Bewley, an expert in women’s health, this could be because children conceived through donation are always born into families who want them too.

“Donor-conceived children are always planned and wanted because one or more of their parents would have had fertility problems,” she said.

‘This could explain their better relationships with their families and their higher well-being.’

However, the study also found that donor-conceived people are at greater risk of problems arising from “feelings of betrayal, difficulties with identity formation and a lack of support in obtaining information about their origins.”

The study found that children had better physiological health if they were told earlier in life that they were donor-conceived. However, there is no legal requirement for families to tell their children the truth about their genetic origins.

These can manifest themselves in a variety of ways, including addiction problems, ADHD, substance abuse problems, mental health problems, disruptive behavior and identity problems, the researchers said.

Dr Charlotte Talbot, another author of the study and an expert in women’s health, said: ‘This is the largest body of evidence we have on the well-being of donor children and adults, but it is a complicated picture.

She added: ‘While most outcomes for this group are the same or better than for non-donor conceived people, qualitative studies showed common themes regarding mistrust and concerns about genetic inheritance.’

However, the authors found that pregnant women who were told the truth early in life generally coped better with these issues.

Laura Bridgens, founder of the charity Donor Conceived UK (DCUK), said: ‘The government and the fertility industry have a duty to listen to the voices of adult donor-conceived children. By doing so, we can create a future where the charity sector does not have to intervene to right the wrongs of the past.’

The authors say that physicians working with prospective parents considering pregnancy through a sperm or egg donor should inform them about the challenges that people conceived this way may face, and should encourage them to disclose their parentage early.

The researchers added that the results may not apply to other communities because the studies they used were primarily from high-income, English-speaking countries.