Rachel’s hair was falling out, her joints were swollen, her mouth had ulcers, and she was exhausted. Doctors sent her away for years… and then she discovered the surprising cause

As she sat in the emergency room, just 19 years old and in her second year of college with painful, swollen ankles—the latest in a long line of unexplained health problems—Rachel Hall realized how sick she was.

The doctor said her latest problem was nothing serious as her partner, now husband, Leon, shrugged off the long list of symptoms she had been struggling with for months.

“Leon described how I had lost weight and my hair was falling out,” says Rachel, from Lewisham, south-east London.

‘I had persistent urinary tract infections, thrush, rashes all over my body, abscesses under my arms and my mouth was full of sores.

‘I had painful, swollen joints in my legs, feet, hands and arms.

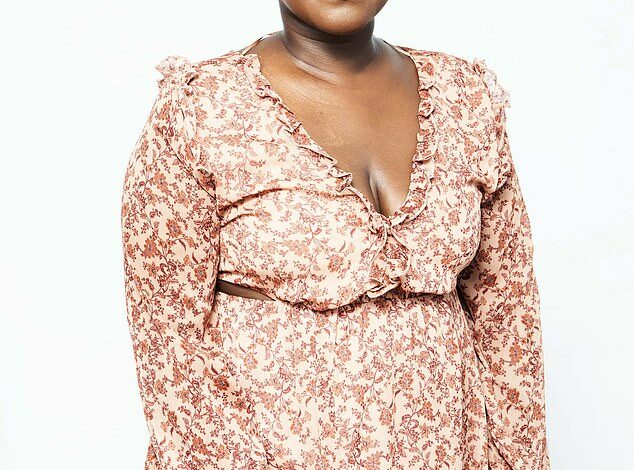

Rachel, now 35, is proof that treatments for lupus have improved, even though there is still no cure

‘I slept constantly, but was always completely exhausted. And it just dawned on me: I’m sick all the time. What could make me so sick?’

It would be another year—during which she visited her doctor or the emergency room more than a dozen times—before Rachel got the answer: She had systemic lupus erythematosus, better known as lupus.

This is a condition in which the immune system makes a mistake and attacks the body’s own cells.

Normally, cells that die are removed from the blood by scavenger cells called macrophages. But in lupus, this process does not work properly and fragments of the old cells remain in the bloodstream.

These fragments are picked up by immune cells, which mistake them for invaders, triggering the production of antibodies that attach to the patient’s cells and tissues, leading to inflammation and damage.

About 40,000 people in Britain have the condition; 90 percent of them are women, for reasons that are not yet entirely clear.

‘It can be very difficult to live with,’ says Professor Christopher Edwards, a consultant rheumatologist at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, who also works on lupus research.

‘Patients experience fatigue, pain and brain fog, which are very disruptive to daily life.’

Almost any part of the body can be affected, from the joints – leading to painful arthritis – to a characteristic ‘butterfly rash’ that spreads itchy and red across the cheeks and bridge of the nose.

Lupus can also damage the kidneys, lungs, heart, brain, nervous system and muscles.

Some patients also experience painful mouth ulcers as the immune system attacks the sensitive lining of the mouth, or hair loss.

The problem is that these symptoms are often confused with other complaints, from eczema (due to the red rash) to cancer.

“Lupus is a great mimic and the symptoms can look like many other conditions, which can be very confusing,” says David Isenberg, a lupus researcher and emeritus professor of rheumatology at University College London.

‘Because it can cause fever, people are examined for infection.

‘And I get patients referred from cancer clinics, and patients who have been misdiagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, for example.’

Lupus can also damage the kidneys (pictured), lungs, heart, brain, nervous system and muscles

Lupus, which can affect virtually any part of the body, can be treated with anticoagulants

One reason for the confusion is that lupus is diagnosed through a combination of the patient’s medical history and blood tests to detect specific antibodies. But these are not always accurate, as not everyone with lupus will test positive, and other autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, can also lead to a positive result.

What exactly causes lupus is unknown; it appears to be related to a combination of genes (people with a black African or Asian background are more at risk); hormones; and external factors such as viruses and sun exposure (UV light accelerates the death of cells, which can lead to a malfunctioning immune system).

A study published earlier this year in the journal Arthritis & Rheumatology suggested that exposure to air pollution increases the risk of lupus. The outlook for people with lupus has improved dramatically thanks to better treatments.

Survival rates four years after diagnosis were only 50 percent in the 1950s. Now about 85 percent of people live 15 years after diagnosis.

But despite such progress, Professor Isenberg points out that someone diagnosed at age 20 still has a one in seven chance of not living to age 35.

“You can see that it is still a very worrying situation,” he says.

Rachel, now 35 and living with Leon, 37, an electrician, and their daughter Naomi, two, is proof that treatments have improved, although there is still no cure.

Her condition is maintained by a cocktail of twelve daily medications – and she recently benefited from taking part in a new drug trial.

Most people with lupus will start their treatment with steroids and/or the drug hydrochloroquine, to reduce inflammation and swelling.

If this doesn’t work, other medications may be prescribed to dampen the immune system’s response, including disease-modifying antirheumatic medications and newer therapies called “biologics.”

Biologic drugs, such as belimumab and rituximab, bind to a type of white blood cell (B cell) that produces the antibodies that can cause the effects seen in lupus.

But all of these treatments have possible side effects.

Long-term use of steroids can thin bones, cause diabetes and lead to high blood pressure by causing the body to retain more water. And like many immune-suppressing drugs, patients can be vulnerable to infections.

Lifestyle changes, such as quitting smoking (which boosts the immune system) and eating a Mediterranean diet rich in fruits, vegetables and oily fish, may be suggested to help reduce inflammation.

But big changes could be ahead.

Earlier this year, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that CAR T-cell therapy – a groundbreaking cancer treatment – also appears to reduce symptoms of lupus.

CAR T-cell therapy works by removing and genetically modifying a type of white blood cell, a so-called T cell.

After chemotherapy to destroy the malfunctioning immune cells, the patient is given an infusion of their new modified T cells, which then identify and destroy the malfunctioning B cells that cause lupus.

After the first treatment, patients appear to be able to produce healthy B cells themselves.

Eight patients with severe lupus who received CAR T-cell therapy went into complete remission and remained there until the end of the study two years later, without having to go back to immunosuppressive lupus medications.

Professor Isenberg says the results are ‘quite sensational’ and ‘a real game-changer’.

The downside is the cost (around £300,000 per patient) and the treatment requires a two-week hospital stay, meaning it is likely to only be offered to the most serious cases, says Professor Isenberg.

Trials are now starting in Great Britain.

In Rachel’s case, she had become so ill at the age of 21 that she had had to drop out of college. After ten months of treatment with steroids and hydrochloroquine to reduce the immune response and inflammation, she felt able to return to university and completed her studies.

She was able to start a successful career as a community liaison manager at a real estate development company, but there have been highs and lows. She often needed painkillers for her hands “because they were so swollen,” she says.

Since then, Rachel has been tried with biologics, daily tablets of a stronger immunosuppressant, mycophenolate mofetil – and at one point even cyclophosphamide, a powerful immunosuppressant used in chemotherapy.

Five months off work was, she remembers, ‘a very horrible time’.

She also worried that her illness could mean she would miss her chance at motherhood. However, after completing chemotherapy in early 2019, Rachel enrolled in a trial where she received two biologic drugs: rituximab mixed with belimumab, which put her into remission.

She then underwent a carefully supervised pregnancy: her daughter Naomi was born in 2021.

Another major flare-up, in 2022, prompted her to retrain as a career coach. Now she looks at life day by day.

“My husband and family have been wonderful this entire time,” Rachel says. ‘I needed a lot of help because I often couldn’t pick Naomi up, take a bath or go outside all the time.’

Her hands remain very swollen, she sometimes has trouble walking, and she has also lost 11 teeth (the lupus has attacked her gums), so she now wears dentures.

She takes 12 tablets a day, including tacrolimus, an immunosuppressant.

Living with uncertainty and ‘a lot of pain’ is tough, she admits.

‘But I am a positive person and I draw hope from periods when I feel a lot better, and from the development of new treatments.

‘I never thought I would have children and yet I have a beautiful daughter.

“I’ll soon be living with lupus for half my life and a lot of good things have happened during that time.”