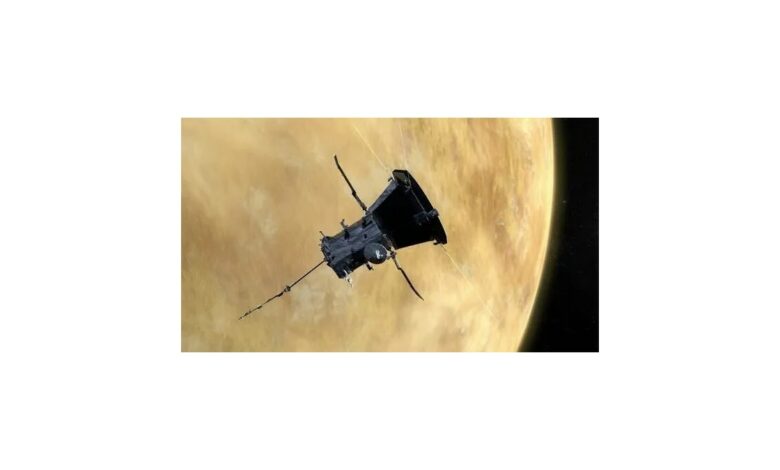

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe makes final Venus flyby before rendezvous with the Sun

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe will make a close approach to Venus on Wednesday, marking its seventh and final flyby of the planet. This maneuver will put the probe on course for its historic dive toward the Sun, bringing it within 6.8 million kilometers of our star’s surface – closer than any man-made object has ever ventured. Nour Raouafi, project scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, described this approach as “almost landing on a star” and compared it to the significance of the 1969 moon landing.

Venus Flybys as Crucial Milestones

The Parker Solar Probe, launched in 2018, relies on it gravity assists from Venus to gradually reduce its distance from the sun, using the planet’s gravity to adjust its orbit. Yanping Guo, Mission Design and Navigation Manager at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, emphasized that this latest Venus flyby is crucial for positioning the probe for its upcoming encounter with the Sun.

Although designed for solar exploration, the probe’s instruments have provided valuable data about Venus. During previous flybys, Parker’s Wide-Field Imager (WISPR) managed to capture images through Venus’ thick atmosphere, revealing surface details such as continents and plateaus. The probe also recorded emissions from Venus’ night side, providing insight into its surface composition and temperature, which is about 860 degrees Fahrenheit (460 degrees Celsius).

A closer look at the Venusian surface

This week’s flight will allow scientists to once again point WISPR at Venus to capture new surface images, including areas of varied landforms. Noam Izenberg, a planetary geologist at APL, noted that this close approach provides a unique opportunity to study differences in Venus’ surface features, potentially revealing information about its geology and thermal properties.

Approaching the limit of the sun

On December 24, the Parker Solar Probe will shave off the sun’s outer layer at speeds of up to 692,010 km/h. Although mission control will lose contact during this close pass, engineers hope to receive a signal confirming the probe’s success on December 27. This achievement could provide important insights into the Sun’s outer atmosphere, its intense heat, and its magnetic dynamics, further advancing our understanding of solar phenomena.