Donating blood, says PETER HITCHENS, has changed his life for the better. Now, with a national deficit, he explains why YOU, like him, should ‘give an armful’

On the rare occasions I do something selfless, I try to keep quiet about it. The Bible warns against boasting about how charitable we are – wise advice.

But I break this rule in one thing. I go on and on about donating blood. This is because I want people to know how much fun it is and get started with it.

It’s partly the ritual of arriving and having your blood tested. Part of it is knowing that you won’t get anything material out of it at all. Here, for once, in a small, crowded room, you can do something just because you want to do it. There is no bargain, no pressure, no payment.

There is always the charm, patience and good humor of the staff. Yes, there is a small, sharp pain when the needle goes in, but it’s not really much. The problem is that most people have no idea this is the case and have never even thought about doing it.

Blood donation was once much more a part of normal life. In large workplaces, which are so much less common, donor sessions would take place in nearby church halls, which are also less common.

It’s been more than sixty years since comedian Tony Hancock recorded his skit about donating blood, in which he redeemed himself after injuring himself with his bread knife.

The program is a historical archive from a vanished world, in which Hancock wears a trench coat and a pork pie hat and the Doctor wears a white coat and heavy glasses and speaks like a caricatured upper-class war professional.

Hancock must donate a British pint (‘almost an armful!’, as he says) instead of the current 500 millilitres.

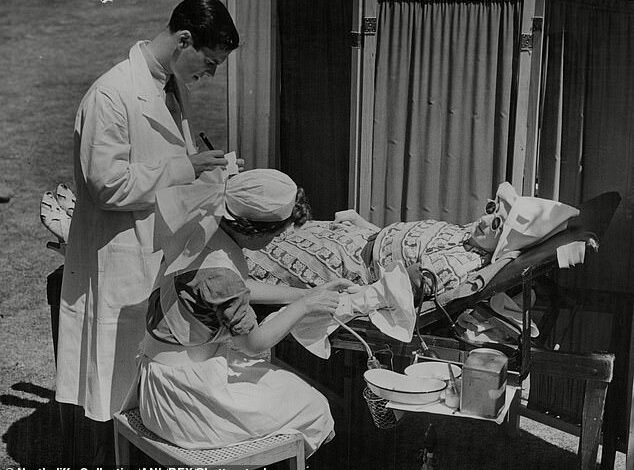

A woman donates blood in the sun during World War II. Blood donation was once much more part of normal life, writes PETER HITCHENS

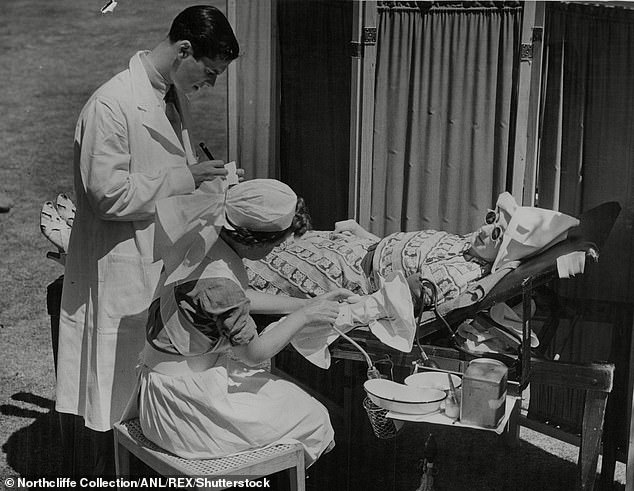

Blood donors give an armful in an NHS clinic. Millions of people see blood donation as an outdated middle-aged suburban practice that is somehow no longer necessary

This air of nostalgia could be the problem. Millions may view blood donation as an old-fashioned middle-aged suburban activity, dating from war and post-war austerity, that is somehow no longer necessary.

Blood donation seems to come from the same era as mass radiography and TB hospitals, iron lungs and wooden crutches.

When I first gave blood at the University of York in the 1970s, the process was wonderfully archaic, with nurses in starched caps and aprons, a reverent silence during the procedure, blood stored in glass bottles and recovery rooms with beds with a iron frame covered with gray blankets with red stripes.

I was never offered a refreshing pint of Guinness afterwards (as some claim), but there was strong tea in a china cup and a plate of Huntley & Palmers biscuits.

The event changed my life for the better in a surprising way.

Donors received a large paper packet with iron pills and were instructed to take them every day for two weeks afterwards with a good breakfast.

Thanks to this instruction, I began to get up early for breakfast as a matter of course, unlike almost all my fellow students who tended to nap until noon.

I found that I enjoyed the early start and breakfast, and never slept in again.

There may also have been other reasons why students did not donate much blood at that time.

According to a widely accepted legend that I have never tracked down but which seems entirely credible to me, a special donation session was held in Oxford in the 1960s so that revolutionary students could donate blood to the Viet Cong guerrillas who were then fighting the Americans in Vietnam.

Many liters of Trotskyist blood were collected and then taken to East Berlin for processing. The story goes that when the East German medics tested for impurities, the Oxford blood was so saturated with marijuana that it all had to be poured down the drain and thus never reached North Vietnam.

After all, the blood people must be careful that what they put into sick and injured patients does not become contaminated.

Today, the donor faces a terrifying form in which, before donating blood, he or she must confess to drug abuse, some rather liberated forms of sexual activity, or some fairly exotic travel (you would be amazed at how many rather ordinary places there are). suspected due to insect-borne diseases such as West Nile fever). Dental work can pose a risk.

A close-up of a man donating blood. About 47,500 donors give blood every week, and hospitals need about 113,000 donations per month, but the short shelf life means supplies must be constantly replenished

I sometimes get frowned upon when I admit that I took paracetamol for a headache a few days earlier, but generally it goes a lot further. This may also turn some people off, but it is necessary.

It was almost certainly a shortage of donors that led to the horrific scandal of blood contaminated with hepatitis C and HIV that lasted from the 1970s to the 1990s. In an effort to treat and help people with haemophilia, Britain obtained blood products from the US, much of which came from blood that had been paid for and therefore should never have been used.

It is very likely that paid blood or blood products have been provided by people with infected or otherwise dangerous blood. As a result, tens of thousands of men and women became infected with hepatitis C and HIV through contaminated blood or infected clotting factor products. It is estimated that more than 30,000 patients received contaminated blood, resulting in at least 3,000 deaths. Any study of this matter will deeply anger you.

The best response would be to start donating blood as quickly as possible; that makes a repeat of this shameful tragedy much less likely.

But now something else has gone wrong. Over the summer, the NHS urged people with O-type blood (which can be given to anyone) to donate urgently after supplies in England fell to unprecedented low levels. The shortage followed a crisis caused by unfilled appointments at donor centers and increased demand after a cyber attack hit services in London.

And last week, NHS England rather plaintively asked blood donors to book and keep their appointments – last Christmas saw the lowest monthly donation total since 2020.

It has urged donors to book over the next six weeks to ensure the country has the blood hospitals need this Christmas.

Last December, NHS England collected around 108,000 donations, ten percent less than the monthly average.

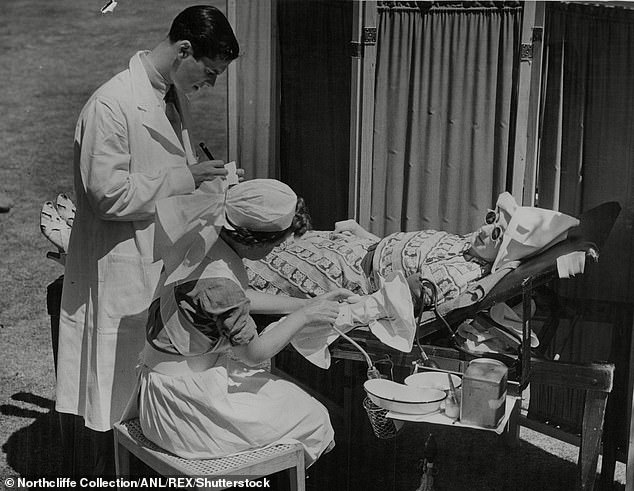

Blood donors were cared for by a female nurse at a health center in Lewisham, South London in the late 1960s/early 1970s

About 47,500 donors give blood every week, and hospitals need about 113,000 donations per month. But blood has a shelf life of only 35 days, so supplies must be constantly refreshed.

None of these shortages would occur if there were more regular donors. And you can’t assume that the existing aging donors will last forever.

There is a limit to how often donors can donate blood: men can donate every 12 weeks, women every 16 weeks.

Donors between the ages of 17 and 24 make up only 7 percent of the donor base. And 200,000 new donors are needed every year to meet demand.

If you’re not one of them, consider becoming one this Christmas. Once you’ve given your first armful, don’t be surprised if you can’t stop.