A modest city that has become the epicenter of American Olympic weight loss — and it’s not LA or NYC

The Olympic craze is dominating Hollywood and the world of social media influencers looking to shed a few pounds.

It has also given millions of obese people a way to accelerate their weight loss when diet and exercise alone aren’t enough.

But it’s not Los Angeles or New York City, but a modest city that is experiencing more economic growth than any other city in America: Bowling Green, Kentucky.

At least 4 percent of Bowling Green residents have a prescription for one of these groundbreaking drugs, significantly higher than in metropolitan areas like New York and Miami, where the prescription rate is closer to 1 percent.

WEIGHT LOSS HOTSPOT: One very modest town that is experiencing this boom more than anywhere else in America: Bowling Green, Kentucky

![A NEW WOMAN: Mary Ellis [right] Lost 80 pounds on Ozempic](http://usmail24.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/88323189-13724707-image-a-14_1723203876967.jpg)

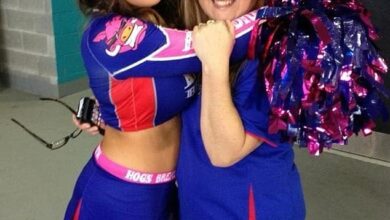

A NEW WOMAN: Mary Ellis [right] Lost 80 pounds on Ozempic

![APPLE OF HER EYE: Mary's husband [left] has also started taking it. The medical spa where they get their injections is so full that they often can't get an appointment](http://usmail24.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/88323193-13724707-Mary_Ellis_right_lost_80_pounds_on_Ozempic_Her_husband_right_sta-m-13_172320379402.jpeg)

APPLE OF HER EYE: Mary’s husband [left] has also started taking it. The medical spa where they get their injections is so full that they often can’t get an appointment

These figures, compiled by PurpleLab Inc., which tracks insurance-covered prescriptions, do not account for the number of people who get their medications from smaller pharmacies that make their own versions, or those who pay out of pocket because insurance doesn’t cover the cost.

Given that a estimated 7.4 percent of Bowling Green’s 75,000 residents are uninsured, but the actual number of residents with a prescription for one of these medications may be higher.

Business is booming at Bowling Green’s doctor’s offices, pharmacies and med spas.

It seems like everyone there is either on one of these drugs or knows someone who is. The idea is to have more and more places in the US become ‘Ozempictowns’.

Marie Ellis wasn’t immediately convinced by the injections. The results of her clinical trial showed that the vast majority of patients had lost up to 20 percent of their body weight after about a year.

She was in her mid-forties, weighed 260 pounds and had tried almost every diet trend with no results, according to a report in Bloomberg.

So she thought she had nothing to lose when a doctor prescribed her Mounjaro, a drug similar to Ozempic, made by Eli Lilly.

She lost 80 pounds in about a year. An added bonus was that she suddenly had no cravings for cigarettes, as she had been smoking since her late teens.

Soon her husband began taking it. The Ellis’ were very enthusiastic about it and convinced Marie’s cousin to get a script for the injections.

Until recently, Marie’s daughter-in-law Savanna used Wegovy, a stronger version of Ozempic that was first approved for weight loss.

She only stopped because she was afraid of the possible consequences for her pregnancy.

Mrs. Ellis joined a local medical spa that provided the weekly injections, albeit cheaper knock-offs.

But it soon became so full that she could no longer make an appointment: ‘If you go tomorrow at 8 a.m., or even earlier, there will be no parking space available.

“You just can’t get in there now. It’s almost impossible.”

Nikki Wilson before her weight loss journey (left). The Bowling Green hairstylist lost about 20 pounds with the obesity medication. She often hears from her clients that they are also taking the injections

She now gets her vaccinations from an out-of-state nurse who sends them in the mail.

Meanwhile, clients of Nikki Wilson, owner of Posh Salon, chatted about the miracle cures. As she dyed someone’s hair, Ms. Wilson excitedly announced she had lost 20 pounds.

She said: ‘Everyone asked me how I lost weight, and I always said: the injections.’

Ozempic, which was initially approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, and Wegovy are essentially the same drug. The latter is just a higher dose. Both are made with the same key ingredient, semaglutide.

Semaglutide promotes weight loss by mimicking the action of GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1), a hormone in the brain that regulates appetite and feelings of fullness.

It also slows down the rate at which the stomach empties, making one feel fuller for longer and less likely to eat more.

Mounjaro and its cousin Zepbound are a bit different. The active ingredient is called tirzepatide and works not only on GLP-1 receptors but also on the hormone glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), which enhances the positive effects.

They have made billions of dollars in pharmaceutical companies Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, and the profit stream shows no signs of slowing down.

Novo reported a profit of about $12 billion last year, its highest annual net profit since 1989. Lilly reported revenue of $11.3 billion and net income of $2.97 billion for the second quarter of 2024 alone.

That financial windfall has trickled down to Bowling Green, where the gym business is booming, med spas are popping up like mushrooms, the local vitamin shop is making big profits on anti-nausea supplements and the restaurant industry is unaffected despite the fact that more and more people are experiencing declining appetites.

Candie Gray, who grew up near the city and takes semaglutide, said: “Do we still go out to dinner with our friends every Friday night? Absolutely.

“Do I eat half of what I used to eat? Yes. You have to figure out how to still function in those social settings.”

Ms Gray, a care home manager, started taking Ozempic in 2022. Her two brothers, in their 50s and 60s respectively, had died of massive heart attacks and her sister warned they could be next.

Candie Gray lost 30 pounds with Ozempic and saw her overall health improve. She takes a version of the drug made by a compounding pharmacy, which, instead of peddling the brand name Ozempic or Wegovy, sells its own very similar concoctions

Gray weighed about 205 pounds at the time, was prediabetic and had high blood pressure. But in just six months on the medication, she had lost 30 pounds, her lab results had normalized, and her commitment to weight loss had turbocharged.

She regularly walks her Great Dane, plays pickleball with her husband and shops online to avoid the temptation of physical stores.

Her progress was rapid, but she hit a bump when her insurance company refused to cover her for the drug. After six months, the company said she no longer met the prior authorization requirements to get it, and they cut her off.

She switched to an imitation of the drug, made by a pharmacy that makes the medicine, for $246 a month. That was more than she paid through her insurance, but far less than the list price of $1,300 a month.

She said, ‘You have a nurse practitioner that you might talk to on the phone, that you might send some labs to, but they have no idea if I’m 125. [pounds] compared to 225.’

Compounding pharmacies are designed to provide medications to patients whose needs are not being met with FDA-approved medications. If a senior takes a medication that is available in pill form but cannot take it that way, a compounding pharmacist would make it into a liquid form.

They are not generics, nor are they FDA-approved. Instead, state pharmacy boards have regulatory powers, meaning that pharmacies selling compounded semaglutide may not be meeting state and federal standards.