A Ukrainian breaker’s journey to the Paris Olympics

By the time Russian troops invaded her home country in 2022, Kateryna Pavlenko was far away in Los Angeles, where she developed a new Olympic sport: breakdancing.

She had moved from Kharkiv, Ukraine, a year earlier, partly to pursue her hobby and partly attracted by a friend who was also involved in the sport. They parted ways, but she stayed, found a vibrant community and trained hard enough to achieve her goal of representing her country at the Paris Games.

Pavlenko, 29, is in Paris, where she will compete in the first Olympic break event on Friday, hoping to win a coveted medal for a home country that is very different from the place where she grew up.

When the war began, she was shocked and incredulous. It couldn’t be true that one of her grandfathers and an aunt had died in Russian bombardments, or that her parents had been forced to flee to the Czech Republic. Her city was collapsing.

“My world was destroyed,” she said in an interview, “but then it was rebuilt.”

In June 2023, Pavlenko and her mother drove for two days from the Czech Republic to Kharkov, in northeastern Ukraine, to explore the lives they had once led in an apartment in the city and a house in a village about 19 miles away.

Nothing was as Pavlenko remembered. The house had been looted while the area was under Russian occupation. Ukraine had retaken the country by then, but by the time they arrived even the cushions had been seized and the carpet torn. The only life left was a family of pigeons nesting by balcony windows blown out by bombs.

Her family’s apartment in the city center was in better condition, essentially untouched since her parents left. The plan was to rent it out while her family was away.

In her old room, Pavlenko leafed through the medals she had won in pioneering competitions in her youth and looked at her school diplomas.

“It’s amazing to see, but it’s not your home anymore,” she said. “It’s really hard to accept.”

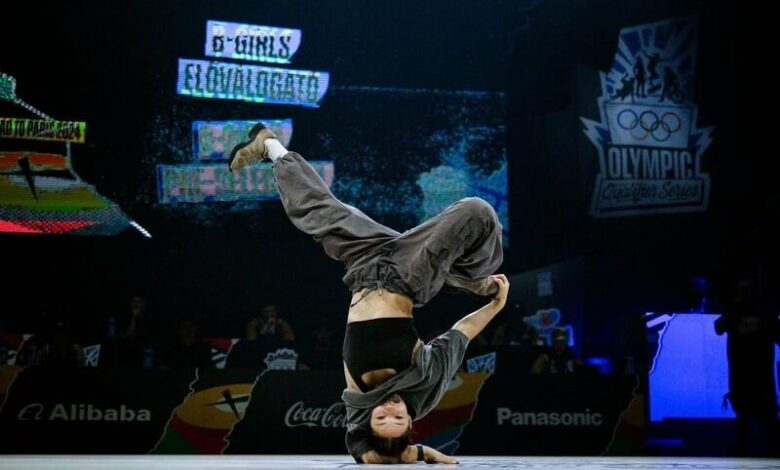

Kateryna Pavlenko during an Olympic qualifying event in Shanghai on May 18. (Haruka Ambai)

Kharkiv was once home to about 1.4 million people, the country’s second-largest city. In the early 2000s, breaking gained popularity and the city became known as the hip-hop capital of Ukraine. Pavlenko signed up for an extreme dance class in 2009 after hearing about it from a classmate at school and immediately fell in love with breaking.

She kept going despite some hesitation from her mother, who was concerned about the many bruises on her body and felt that the sport was not feminine enough.

Yet at 14, Pavlenko began traveling to the other side of Kharkiv, a 90-minute train ride away, for more after-school recess classes. She felt powerful, the queen of her world. Soon, she began winning competitions across Europe. Red Bull sponsored her. And she became known as B-Girl Kate.

During her two-week visit to Kharkiv last summer, Pavlenko realized that her home no longer offered her the same comfort. A walk through a city park terrified her when bomb sirens went off. Everyone around her moved on when they discovered that the neighborhood was not in immediate and immediate danger. But Pavlenko froze. Her head pounded with fear at the thought of more Ukrainians dying in another attack somewhere nearby.

She felt fortunate to be able to return to Los Angeles, where she had an apartment, a work visa, and a job as a stylist at a pop-up clothing store. She also had a clear goal to strive for: a spot on the Ukrainian Olympic team. Breaking was added to the program specifically for the Paris Games, making it the only foreseeable opportunity for athletes in her sport to compete on the Olympic podium.

All she had to do was finish in the top eight b-girls at the end of two Olympic qualifying competitions, one in Shanghai and one in Budapest.

After Kateryna Pavlenko started winning, Red Bull sponsored her. And she became known as B-Girl Kate. (Haruka Ambai)

She reunited with the rest of the Ukrainian breaking team, including four other competitors, in Poland ahead of the first competition in Shanghai, building a bond with her teammates while trying not to focus too much on the idea that they would likely be competing against each other.

But her nerves still started to show.

She reeled under the pressure she saw in Shanghai, and she saw other athletes facing similar stressors. She lost sleep, couldn’t eat and lost in battles to two eventual Olympians, American phenom Logan Edra, known as Logistx, and China’s Zeng Yingying, who goes by Ying Zi.

But she saved herself enough to put herself in a good position for the next qualifying event by letting go of her worries about the score during the final event and relying on the powerful spins, handstands and other moves she knew she could show. When it all came together, she thought, “This is why I live.”

She cleared her head with a trip to Joshua Tree, California, in preparation for her last chance in Budapest at the end of June.

This time she slept well and felt much more prepared to compete. She got into a fight with one of her teammates and training partners, Anna Ponomarenko, and survived. Pavlenko had qualified for Paris and celebrated with a doping test, media interviews and celebratory shots with other competitors.

It was a blissful haze that ended in exhaustion and overwhelming gratitude.

And Ponomarenko, who goes by Stefani, eventually qualified as well, the only other Ukrainian to qualify for the women’s break competition. Oleg Kuznietsov, who goes by Kuzya, competes in the men’s division; he was born in Siberia, Russia.

Recently, Ukrainian Olympic officials advised their athletes to avoid the Russians and Belarusians who competed as neutral athletes. Pavlenko agreed that non-communication would be the best approach. None of the 32 athletes with the neutral designation are breaking.

“I want to represent my country because that’s where I grew up, that’s where I started breaking, that’s what shaped me as a person, as a woman,” Pavlenko said.

Kateryna Pavlenko dreams of shaking hands with Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the president of Ukraine. (Little Shao / WDSF)

The women’s competition is scheduled for Friday and the men’s competition for Saturday at La Concorde, the city park that also hosts 3×3 basketball, skateboarding and BMX freestyle competitions.

There, on the site of one of the world’s most famous squares, near the Seine River with its towering obelisk in the heart of the city, the breaking will play out in a series of short head-to-head battles, with early rounds whittling the women’s field down from 17 to eight b-girls. From there, the tournament becomes a single-elimination knockout. The format, with 16 competitors on the men’s side, has similarities to basketball and soccer’s pool play and knockout rounds, but will be played out entirely in just a few fast-paced hours.

During each battle round, breakers have a short window to perform their best moves. After each round, nine judges each choose a winner based on technique, execution, musicality, and originality. The judges’ scores are weighted, meaning they can determine that one breaker has overwhelmingly outperformed the other in a given round.

During the early round-robin stages, each fight has two rounds. The knockout fights have three rounds each.

In the weeks leading up to the Games, Pavelenko returned to Warsaw for her final training camp. Her days consisted of training and taking a few hours off, watching videos of past performances, and maintaining healthy eating and sleeping habits.

She said she was focused on bringing back the “old Kate,” the one who focused on her love of dance rather than nitpicking the sport. If she could bring a stronger, more playful look to the Olympics, she could win a medal, she told herself.

Physically, she felt ready. Mentally, she had work to do. She began to feel that she was not prepared enough. She felt guilty because she had a cocktail with an old friend one night. Her inner critic took over.

“I’m losing myself more and more, and for this competition I need myself the most,” she said. “I need to feel good in my head … be confident, no matter what.”

Talking to her therapist helped. So did journaling, affirmations, and reminders of how rare it is to make it to the Olympics. She had already accomplished something few would ever experience—how cool is that, she thought. Her mental strength returned.

When Pavlenko arrived at the Olympic Village on Tuesday, she closed her notebook and stopped training except for light warm-ups. She was as ready as she would ever be.

She expects that she will not have enough time on Friday to let her nerves run free and fully focus on the freedom she feels during the performance.

Being in the athletes’ village is fun, she said, mixing with elite athletes from around the world. “Everyone wearing their team uniforms, exchanging pins, food is open 24/7 — that’s good news,” she said in a text message with a laughing emoji. A Ukrainian flag hangs from the balcony of her room.

She dreams of standing on a podium with a gold medal around her neck. A bouquet of flowers in her arms. Maybe she will eventually shake hands with Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the president of Ukraine.

If that were to happen, “I will be a hero of the country,” Pavlenko said. “In such times it would be great to represent Ukraine and win a gold medal, so that people will talk more about Ukraine and not forget about us.”

(Top photo of Kateryna Pavlenko during an Olympic qualifying event in Budapest: Little Shao / WDSF)