Andrew Scott Is Always Mesmerizing. Here’s How He Does It.

There are actors who, no matter the size of their role or the context of their performance, always command attention. Andrew Scott, who recently appeared as the slick, intriguing protagonist in the Netflix series “Ripley,” is one of them. He is compelling to watch, his emotional notes carefully constructed, with playful touches of chaos that always leave room for moments of discovery and surprise.

Below are some of Scott’s favorite acting performances and how his popular roles reflect an actor who excels at his craft.

The fool

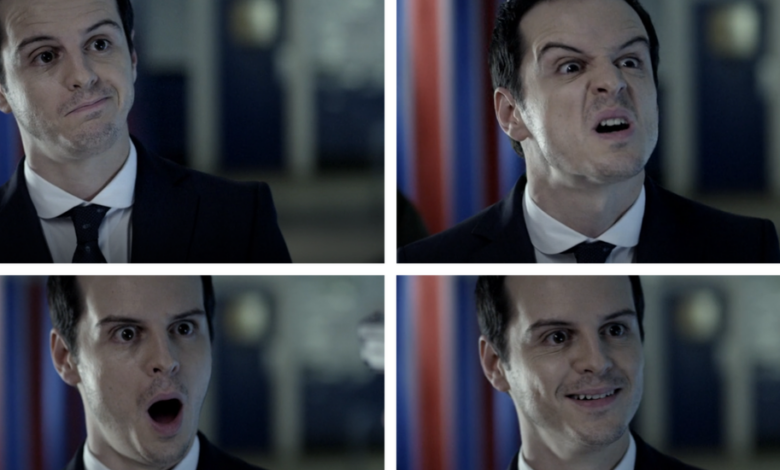

In Scott’s breakthrough role on “Sherlock,” he plays Moriarty, the criminal mastermind opposite Benedict Cumberbatch’s modern-day Sherlock Holmes. From Scott’s first appearance in the Season 1 finale, he electrifies an already energetic show.

Cumberbatch sets the tone for “Sherlock” with his brutal, quick wit; deductions roll out of his mouth with strict precision and an impersonal monotone. Scott’s arrival and his erratic, sing-song voice break this rhythm. There’s a menacing playfulness not only in his rhetorical delivery but also in his facial expressions. It adds a new dimension to the show.

In their first confrontation sceneSherlock points a gun at Moriarty and asks, “What if I shot you right now?” Moriarty responds with a cartoonish look of terror that starts at the top of his head and spreads downward: his eyebrows shoot up, his eyes widen, his mouth falls open, and his neck pulls back.

The speed with which his expressions unfold underscores Moriarty’s dangerously volatile temperament; when he threatens Sherlock again, he speaks softly at first, then bursts out mid-sentence, his face contorting hideously as the timbre of his voice drops to an eerie rasp. Just as quickly, the moment is over: Moriarty reverts to his lighthearted tone of villainy and apologizes.

For such a stylized performance as Scott gives, the character is always believable, especially in this world of grand crimes, intricate designs and eccentric genius. Sherlock is the eternal, steadying force, playing the violin and wandering through his mind palace, while Moriarty is the agent of chaos who acts as his party.

The Charmer

The most striking element of Scott’s performance as the so-called hot priest in “Fleabag” is his shy smile. When he is introduced in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s delightful comedy-drama, during a family dinner, his smile is polite and disarming.

It’s when he and Fleabag are on a cigarette break and he casually throws a curse word at her as she walks away that a boyish grin appears on his face. His eyebrows raise slightly in an expression that suggests he’s challenging her.

Part of his charm is a matter of contrast: he’s a saintly preacher who must offer spiritual guidance, but he’s also a foul-mouthed heavy drinker who can barely hide his sexual desires. As he’s finally about to give in and sleep with Fleabag, his cheerful smile fades, a corner of his mouth lifting in a look of satisfaction, but there’s no joy behind the expression. His gaze is hard and resigned to the transgression, and there’s only a shadow of his shy smile beneath it.

At the end of the series, the priest says he’s not sure whether the euphoria he’s feeling is from God or from Fleabag, and Scott’s performance gives us a clue to the answer. Scott’s exuberant energy—that almost manic, kinetic charge he often imbues his characters with—is most vivid in the scenes where the priest talks about God. Scott’s priest realizes, despite his love for Fleabag, that she hasn’t changed his faith. She’s strengthened it.

Scott’s charm is on display in another way in the new Audible podcast adaptation of George Orwell’s “1984.” His audio performance deceives the senses: You can somehow hear the smirk on his face as he plays O’Brien, an undercover agent masquerading as a revolutionary in a dystopian society. Scott leans on the lilt of his natural Irish accent, and his exaggerated shifts in pitch, coupled with the precise way he hangs each syllable on the air and marks time with cryptic murmurs and pauses, create an alluring mystery.

The wounded man

Scott’s most recent big-screen role was in the 2023 film “All of Us Strangers,” which showed how much melancholy he can bring to a performance through nuanced silences and stillness. He plays Adam, a lonely gay screenwriter who encounters a stranger named Harry and then returns to his childhood home to find his parents dead, just as they were decades earlier.

Scott’s performance is muted, his eyes constantly contemplative, his expression one of grief hardened into a stone exterior. Even his grief is restrained; in a scene where he discusses his sexuality and childhood bullying with his father, he is calm and dismissive of the difficulties he has faced until his father begins to sob. Adam’s face and torso crumble as well.

Perhaps Scott’s most devastating performance was captured in a 2012 short film, in which he delivers the monologue “Sea defense,” by Simon Stephens.

Playing a man telling a personal story of love, faith, and devastating loss, Scott realistically captures the wanderings, interruptions, and distractions that people often use in conversation. He uses the entire studio space behind him, wandering around, pacing, looking out windows, creating a complete sense of the environment around him. His mannerisms are precise and seem to deliberately create parallels in his storytelling; a large, grasping gesture can show both his young daughter reaching innocently upward and his attempt to summon a word from thin air.

The villain

In the hands of the wrong director and the wrong lead, Tom Ripley, the sociopathic con-man-turned-murderer from Patricia Highsmith’s best-selling book series, could easily be flattened into a common criminal. What makes Ripley more than just a villain in the latest mystery thriller is his elusiveness; his Ripley is often psychologically opaque and unpredictable.

Scott’s performance in “Ripley” is understated but not restrained. He leaves just enough space for the audience to see Ripley’s thoughts and emotional responses, while leaving the rest open to interpretation.

Scott’s charisma usually shines through his characters, who are effortlessly seductive even at their most villainous. But Scott shows his charm as Ripley, who is neither polite in his social interactions nor his crimes. The quiet that this Ripley exudes barely masks the frenetic energy beneath the surface. In the scenes where Ripley suspects he’s about to be caught, he smiles and makes small talk, trying to relax his demeanor in a seeming act of confidence. But his eyes are tense and focused, like those of an animal spotting a predator.

Ripley is stiff; his conversations are often rehearsed, from his answers to the way he sits. Perhaps the most common emotion Scott displays in this character is shame. When Ripley’s unrefined taste is attacked — “Who in the world “I would wear a purple paisley cloak,” says Ripley’s would-be victim with a mocking laugh—embarrassment flashes across his face for a moment, in the hardened lines around his mouth and a quick downward glance. Then it’s gone as quickly as it came.