For more stories about Wimbledon, click here and they will be added to your feed.

A hundred years from now, a tennis nerd will ask the floating hologram next to his ear about the best male players of the early 21st century.

The hologram will wax poetic about a triumvirate of players known as the Big Three: Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic and Rafael Nadal. They ruled the sport before the advent of nuclear-powered strings and 200-mile-per-hour serves, winning some 70 Grand Slam titles between them.

Then, almost in passing, a few others are mentioned who won some of the major tournaments on Earth, before the tours were expanded to include the exoplanets of Alpha Centauri.

“Stan Wawrinka and Andy Murray each won three Grand Slams and were the second best of the Big Three era,” the hologram will say.

People of 2124: Don’t trust your holograms, especially when they mention that in his final Wimbledon match, likely the penultimate tournament of his career, he had to endure a 21-year-old who decided at the last minute to pull out of a mixed doubles match with him. Emma Raducanu, his compatriot who is reviving her fledgling career with a run in the second week of Wimbledon, withdrew, prioritizing her chances of winning the singles match in an open draw over a chance to share the court with Murray, her idol, for what appeared to be his final match on the grass at Wimbledon.

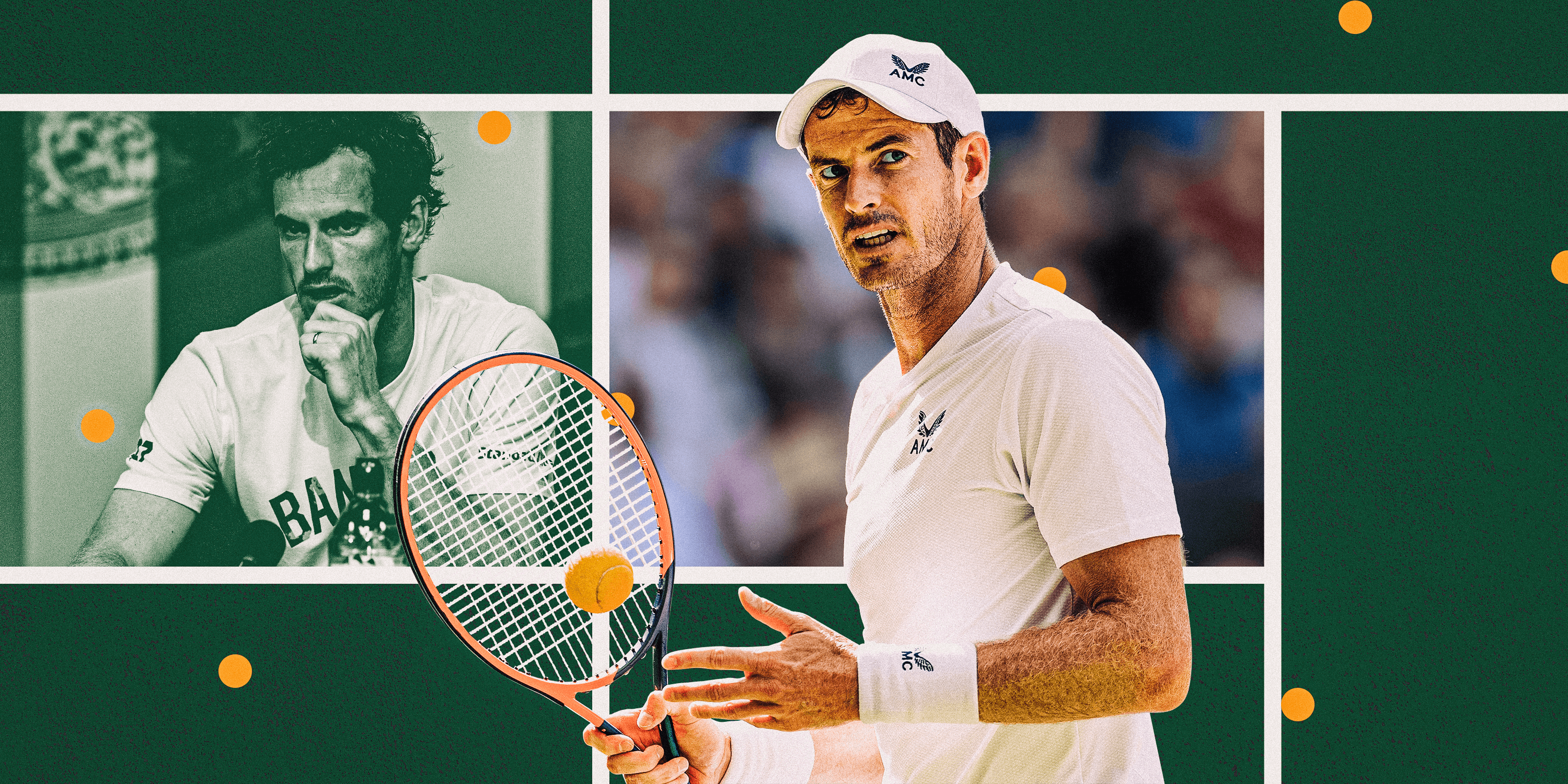

Andy Murray spent his career defying expectations under the pressure to live up to them. (Mike Hewitt/Getty Images)

So, barring a planned doubles performance at the Olympics, this is really the end for Wimbledon, allowing the effort to secure its rightful place in the tennis lexicon to begin. No disrespect to Wawrinka, a fine player with a fine career, but Murray has spent the last three decades breaking the conventions, the ultimate thorn in the side of so many tennis assumptions, of having holograms and the tennis nerds who use them remember him in the same sentence.

Perhaps this is what has kept Murray going for the past year and a half, desperate to make one more run at the business end of the sport’s biggest events, long after pretty much everyone could see it wasn’t meant to be. Perhaps this is why he limped onto the court to face the world’s best players when climbing stairs became a struggle.

In March, Murray found himself in a hotel gym with Brad Gilbert, the former pro and longtime coach, in Indian Wells, California, late at 4 a.m. An early-rising insomniac and a jet-lagged Scot chatting about new racket technology, Murray told Gilbert he might have found a new stick that could give him a little extra… something.

Something that would prove he still had magic.

Perhaps Murray stuck around simply because he loved just about everything about his court: the feel of the racket in his hands, the life of a globetrotting superstar, the incomparable highs that came with the heat of competition. He burned with jealousy when he saw players like Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz start their journey. He would have gone back to the beginning if he could, not to change anything per se, but simply because he wanted to do it all again.

“I want to play tennis because, you know, I like it,” he said last year at Surbiton, where he played a Challenger tournament instead of Roland Garros to get extra time on the grass before Wimbledon.

“I love it. It’s not like this is a huge job for me.”

Murray and his new Yonex racquet in Geneva, earlier in 2024. (Fabrice Coffrini/AFP via Getty Images)

It never really was, even though it seemed that way as he grunted his way through 1,000 games. But it was also the joy of playing a game he loved, and proving just about every assumption about him and his sport wrong.

First there was the idea that a Scot might even be good at junior tennis. Golf perhaps, but not tennis. Too many talented kids from friendlier tennis climates and venues to compete with. There weren’t many indoor courts and not too many expert coaches, other than his mother, Judy, and certainly not enough top competition to help him develop, other than his older brother, Jamie.

Murray didn’t let this deter him, whether it meant training harder during those formative years or taking the radical step that few of his peers were taking.

“My mom did her best to create an environment, not just for the two of us, but for the players who were at a certain level of performance, and to bring us together as much as possible because she understood how difficult it was,” Jamie Murray said in an interview last year.

“Andy obviously left when he was 15 — he went to Spain, he made the decision: ‘I really want to be a tennis player and to do that I have to go to Spain and train’ and he was obviously very stubborn about it and he went. I stayed at home.”

Habits are formed early in tennis. In most cases, a 25-year-old’s forehand won’t look all that different from a 15-year-old’s. The same goes for stances and approaches, such as Murray’s tendency to ignore conventional wisdom.

So Andy, nice junior career, but you probably won’t be able to win much against Federer and Nadal, or even your junior buddy Djokovic. Born at the wrong time. Bad luck.

He defeated Nadal seven times and Federer and Djokovic eleven times.

Murray and his friend from Serbia play doubles together at the 2006 Australian Open. (Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

Ok Andy, it’s nice that you occasionally get a win against top players, but a Brit hasn’t won a Grand Slam in almost a century. That can’t be.

And then he won the US Open in 2012 and Wimbledon in 2013 and 2016, despite pressures probably no modern player has ever felt on Centre Court.

And don’t forget the losses, including five Australian Open finals, only to Djokovic or Federer. That’s like so many of his losses in the finals or semi-finals of major tournaments.

“I’m playing against guys who win these tournaments about 12 times a year in their career,” he said in an interview last year.

And yet he still won 46 tournaments, including 14 Masters 1000 titles, the level just below a Grand Slam, far more than any player of his era except the Big Three. I don’t want to single out Wawrinka, but he won 16 titles, only one of which was a Masters 1000.

Well done Andy, but #1 in this era is out of reach.

He arrived there in 2016, when Nadal and Djokovic were still in their prime and Federer still had three years to win Grand Slams and reach finals.

It was not easy.

GO DEEPER

Fifty Shades of Grey by Andy Murray

“I was just doing everything, you know,” he recalls. “I was on the track. I was in the gym, I was lifting weights, I was doing core sessions, I was doing hot yoga, I was doing sprint work, speed work, I was just throwing everything at myself.”

He paid a price for that, putting so much strain on his hip that he had to undergo resurfacing surgery in 2019. Doctors told him he’d be lucky if he could ever hit tennis balls with his kids. He turned those words into a challenge to prove them as untrue as possible, and climbed to No. 36 in the world rankings last summer.

He enjoyed being a guinea pig of sorts, one of the first elite athletes to test the limits of a hip made largely of metal.

Murray’s hip was a problem at first, but then became one of the symbols of his career. (Ashley Western/CameraSport via Getty Images)

“Nobody really knows where that line is,” he said.

“I want to see what that is.”

But that was all just his competitive, wayward nature, which extended beyond the field to his empathy for issues and people that the sport sometimes represses or tries to avoid.

Male tennis players have never shown so much respect for the women’s game. Murray talked about it and hired a female coach, Amelie Mauresmo.

They also rarely speak ill of their fellow players, or support an action that would cause significant discomfort to one of them. Murray was among the first to criticize the ATP Tour for its months of hesitation before announcing that it would investigate allegations of domestic abuse against Alexander Zverev. The German settled a case involving charges filed by his ex-girlfriend and the mother of his child out of court at the French Open.

Murray bought an apartment in Miami and studied the training and business habits of NBA players to see what he could learn from them. When he became dissatisfied with the way management firms treated athletes, he opened his own shop. He bought an old, run-down hotel in Scotland where his family celebrated weddings and other important events, even though advisers told him it was a terrible idea. He and his wife, Kim, have transformed it into a luxury destination. He collects art.

Murray joins Kim and his team at Wimbledon after finally winning the tournament in 2013. (Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

So of course he was never going to leave the tennis court when everyone started planning his retirement. Of course he was going to do it his way, try to squeeze every last chance he may or may not have had for glory out of his body, and that new Yonex racquet he tried out earlier this year, which led him to Gilbert in Miami at 4 in the morning.

He wouldn’t simply rest on his laurels, and would even attempt to return from back surgery on a spinal cyst in time for a final singles match on Centre Court that he would likely lose. There’s a reason Murray holds the record for coming back from two sets down, overcoming that deficit 11 times, most recently at the 2023 Australian Open when he lost five hours and 45 minutes and defeated Thanasi Kokkinakis 4-6, 6-7 (4), 7-6 (5), 6-3, 7-5 just after that magical time, 4 a.m..

After living and playing tennis like this for about 30 years, old habits die hard.

Murray knew the end would come one day.

It’s one thing to accept conventional wisdom. Defeating time and aging is another. Murray simply had to fight his best, which was the easiest part of the hardest part, because he’s never known any other way.

(Top photos: Joe Toth/AELTC Pool, Simon Bruty/Anychance / Getty Images; Design: Dan Goldfarb for The Athletic)