As a teenager my legs were amputated – I bought a skateboard to keep up with my kid

A GERMAN woman born without legs and with deformed hands lives a richer life than most could ever imagine.

A medical condition she had since birth required her legs to be amputated in her teens.

Hulya Marquardt41, living in Stuttgart, was born with a split hand/foot deformity, an unusual genetic condition.

At just over a metre tall, her lack of limbs has never held her back. She is a wife, mother, owner of a fashion boutique and a prominent activist for disability rights.

“By the time I was six years old, I had already had 21 surgeries to improve my mobility,” Marquardt said.

“The operations were somewhat successful. I was now able to walk with the help of metal pins that were placed in my legs to straighten them.

“But when I was 18, one of the screws in my legs came loose. I developed an infection that quickly escalated to sepsis.”

To save her life, doctors had no choice but to amputate both of her legs above the knees. The amputation left Marquardt with stumps barely long enough for prosthetic legs.

“I remember thinking, ‘This can’t be the end for me,’” Marquardt recalls.

“I had already adjusted so much in my life. I just said to myself, ‘You have to keep going. There is always a way forward.'”

Doctors predicted that Marquardt would have to live in a nursing home. They did not believe she would be able to use a manual wheelchair, given her hand deformities.

But Marquardt had other plans. Instead of accepting a life of limitations, she decided to adapt and make the best of her situation.

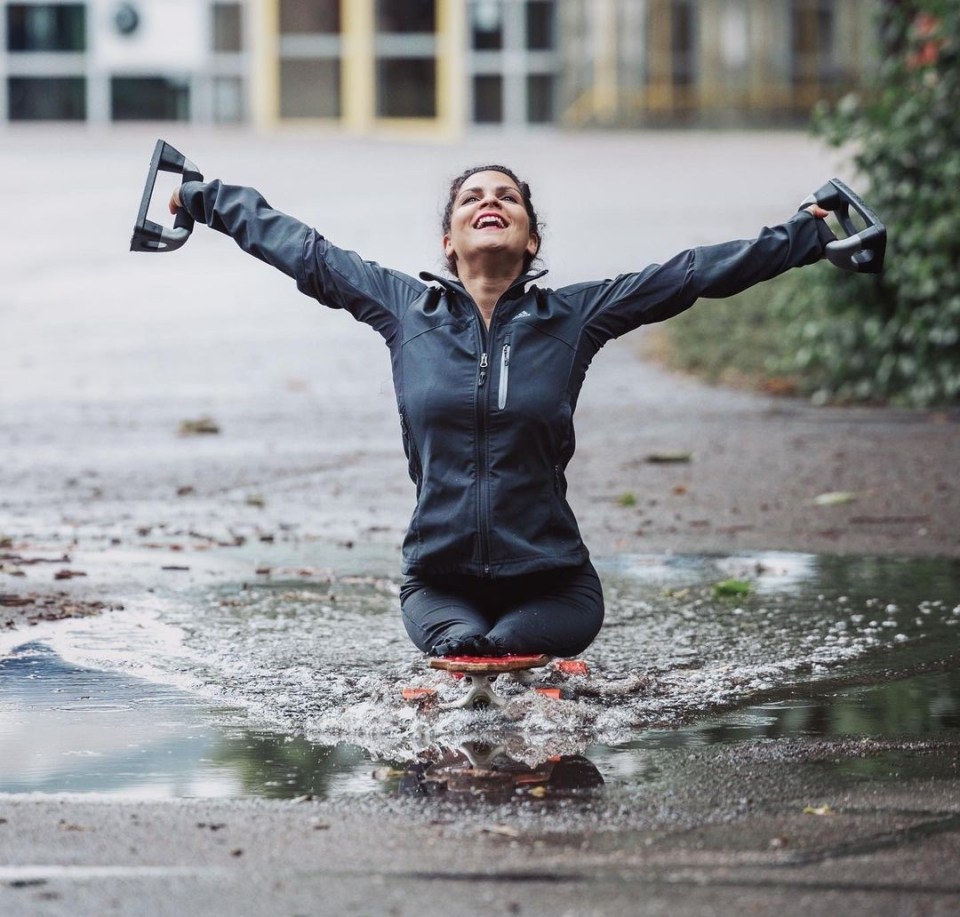

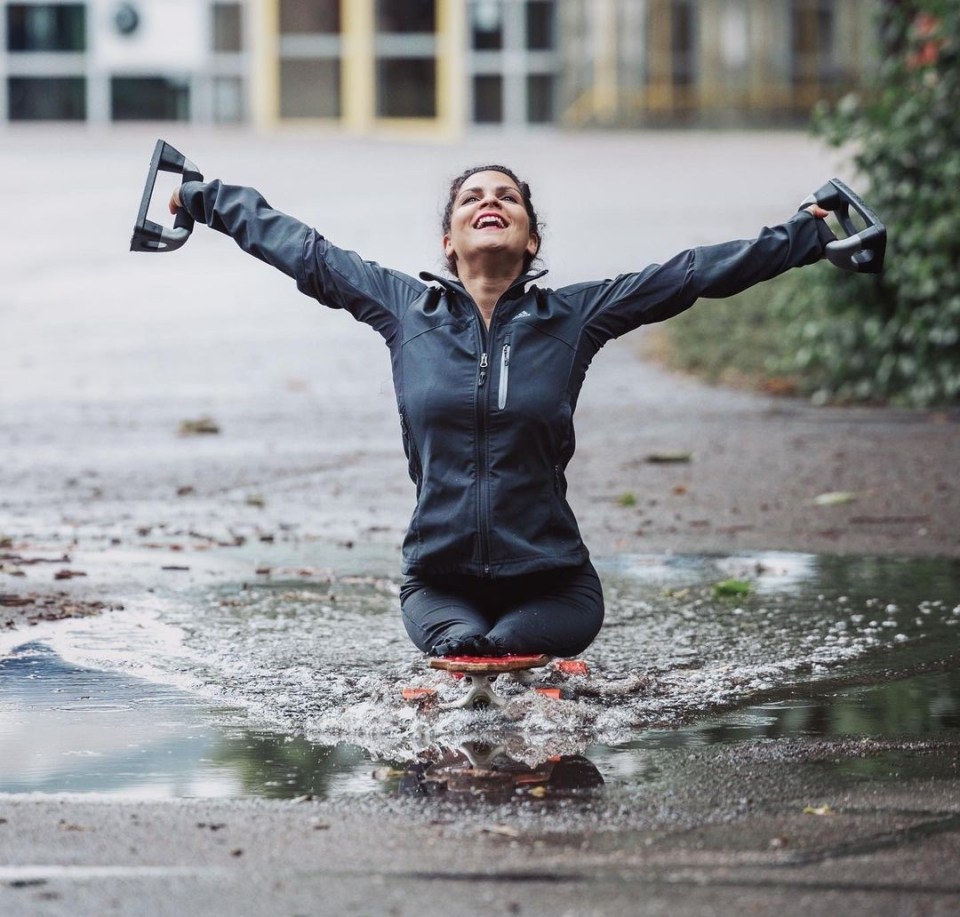

“I learned to walk on my hands, use a skateboard to get around and even drive a hand-cranked car,” she said.

“I got an office job and was able to live independently.”

But Marquardt’s story doesn’t end there. In 2014, she met her current husband, Dennis, who worked as a high school teacher. The two fell in love and traveled the world together.

“I’ve had a kind of ‘crippled pride’ all my life,” Marquardt admitted.

“I wasn’t going to let my disability stop me from living my life. I wasn’t going to let it dictate what I could or couldn’t do.”

In 2019, Marquardt and her husband discovered they were expecting a child.

“I knew people would question my ability to be a mother, given my physical condition. But I knew I could be just as capable a parent as anyone else, just in my own unique way,” she said.

When their son Rangi was born in May 2020, Marquardt approached motherhood with the same resilience and creativity that had marked her life up to that point.

Instead of relying on others, she found ways to care for her son independently.

From breastfeeding to changing diapers, Marquardt did everything an able-bodied mother would do.

“I used a custom-made wheeled basket made by my father-in-law to transport Rangi around the house while I crawled across the floor,” Marquardt said.

“I didn’t want Rangi to miss out on anything because of my disability.”

As Rangi became a toddler, it became increasingly difficult to keep up with him. However, Marquardt adapted again, using her skateboard or walking on her hands to play with him.

“People would stare at me when I was out with Rangi, but I never let it distract me,” Marquardt said.

“I knew they were curious, but my focus was always on my child and making sure he had the best possible experiences. I want him to grow up knowing that you can do anything, no matter the challenges.”

People often see me crawling or skateboarding and think there is no dignity in that.

Hulya Marquardt

In addition to her role as a mother and wife, Marquardt is also a fervent advocate for the rights of people with disabilities.

She uses her platform on social media, especially Instagram, to share her experiences and raise awareness about the challenges and misconceptions surrounding disability.

With over 212,800 followers on TikTok and 295,000 on Instagram, her social media pages are a source of inspiration for many.

“There are a lot of misconceptions and I want to break them. I want to show that we are capable and strong and deserve the same opportunities and respect as everyone else,” she continued.

Marquardt is also a prominent figure in the German disability community, where she campaigns for greater accessibility and equality.

Her message is clear: disability is just one aspect of human diversity, not something to be pitied or ashamed of.

“People often see me crawling or skateboarding and think there is no dignity in that,” Marquardt said.

“But there is dignity in living life on your own terms, in not being limited by society’s expectations.

“We need more accessibility and more understanding, but above all we need to change the way we look at disability.

“My body may look different, but that doesn’t mean I’m less capable or less worthy of living life to the fullest.”