As Maui Invitational marks 40 years, it returns to a home forever changed

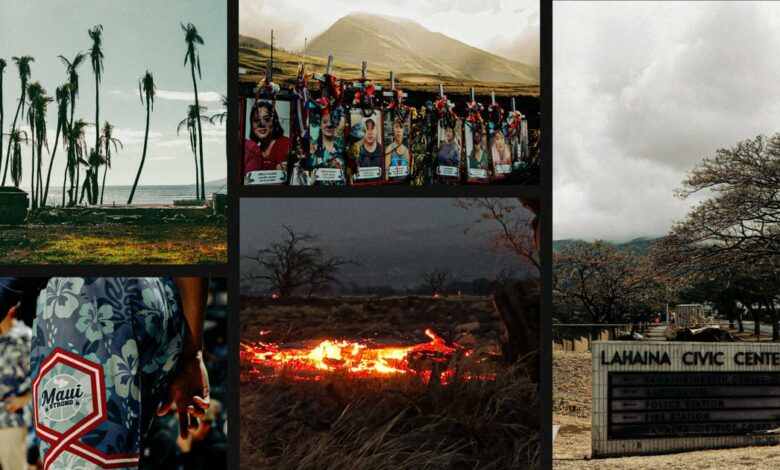

LAHAINA, Hawaii — You cannot miss it, just across the gravel parking lot behind the Lahaina Civic Center: burned brush, as far as the eye can see.

Charred shrubs practically surround the place, a semicircle that looks like it should’ve swallowed the gym, best known for hosting college basketball’s famed Maui Invitational. But it didn’t. Instead, a thin layer of rocky rubble serves as a makeshift boundary, a barrier from the beige that sweeps eastward up the hill toward the Maui mountains. Follow the sightline farther down Honoapiilani Highway, which runs parallel to the glistening Pacific, and your eyes meet Lahaina, one of Maui’s most populous towns, or at least, what’s left of it.

Which, 15 months after the deadliest wildfires the United States has seen in a century, is not much.

There are still more bulldozers than buildings. More piles of debris than people. The basketball hoops at Wahikuli Terrace Park are still standing, but the backboards are visibly scorched, and the court has been converted into a construction zone. Cement cinderblocks are the reminder of where families’ homes once stood. Quick blasts from nail guns — psst, psst — punctuate the steady sound of traffic driving by, and of waves washing up on the shore. A single Hawaiian flag juts out of the emptiness, rippling in the breeze. Directly downhill from it, posted on a black mesh barrier, are three 6-by-15 canvases of colorful children’s drawings adorned with messages:

Maui Strong.

We will adapt.

Maui can get through anything.

On the 40th anniversary of the Maui Invitational, the focus isn’t on how a tiny tournament in the middle of the Pacific has, somehow, endured for four decades. The three-day event regularly draws some of the sport’s best ball clubs — this year’s eight-team field features No. 2 UConn, No. 4 Auburn, No. 5 Iowa State and No. 10 North Carolina — and coaches wearing Hawaiian shirts and leis on the sidelines has become iconic.

Instead, the Maui Invitational’s homecoming after being played in Honolulu last year arrives against the backdrop of an island, and community, still reeling from August 2023’s devastating wildfires: blazes that claimed at least 102 lives, displaced thousands of locals and flattened an entire town.

“We’ll forever refer to our community,” said Maui mayor Richard Bissen, “as pre-fire and post-fire.” Locals acknowledge it might be another decade — minimum — before the area approaches what it was before last August.

Recovery is ongoing 15 months after the devastating fires. (Hiroto Sekiguchi / AP)

How, then, do the two coexist? This beloved basketball tournament and a people whose livelihoods depend on tourism — but many of whom are still hurting, still healing and who aren’t fully ready for something this scale? Who, frankly, aren’t sure how to feel about 6,000-plus people suddenly descending on their island and bringing a national TV spotlight with them.

“I’m sensitive, and (we’re) still in the healing process,” said Luis Fuentes, who lost his catering building and kitchen in the fire, “but part of the healing process is being able to do something about it. And this — for me, and my family and my team (of employees) — is doing something about it.”

As North Carolina’s team plane touched down in Maui in 2004, Roy Williams was steaming mad.

His Tar Heels — ranked fourth nationally that preseason — had flown to Hawaii straight from California, on the heels of their season opener vs. Santa Clara. But down starting point guard Raymond Felton, UNC actually lost to the lowly Broncos (who finished that season with a losing record).

“Ticked off is better English,” Williams said, “but I was pissed off.”

As UNC’s players boarded the team bus, they were intoxicated by the ocean out the window. But when UNC pulled up to its team hotel, Williams told his players to stay seated. He let all the coaches’ wives and families off the bus, then stepped into the center aisle: Guys, we’re not in Maui yet. We’re going to that gym, and we’re going to practice.

“I got after them,” Williams said, “as hard as I’ve gotten after any team in any practice, even to this day.”

Not only did UNC tear through the Maui Invitational days later — beating BYU, Tennessee and Iowa by a combined 63 points — but it lost only three more games the rest of the season. As it turned out, the physicality Williams demanded in Lahainaluna High School’s gymnasium carried for five more months, ultimately culminating in his first national championship. UNC celebrated its tournament title with dinner at Longhi’s on Ka’anapali Beach, where forward Reyshawn Terry played an impromptu drum set after that night’s band had finished.

No wonder Williams says Maui is his favorite place on Earth. All three of his North Carolina title teams — in 2004-05, ’08-09, and ’16-17 — won the Maui Invitational early in their championship seasons.

“When we got there, we knew a little bit about our team,” Williams said, “but when we left there, we knew a lot about our team.”

But Williams is far from the only coach whose ball club has benefitted from three games in Hawaii. Michigan in 1988-89 and UConn in 2010-11 are also among the teams that first won Maui before eventually winning it all. Just last season, Matt Painter and Purdue emerged victorious in arguably the tournament’s toughest ever field — with five top-11 teams, four of which later made the Sweet 16 — and never slowed down en route to the national championship game.

“It’s basically big-time basketball in a high school gym,” said ESPN analyst Jay Bilas, who has broadcast the event for more than 20 years. “The games, it seems like they’re always great.”

How does that always happen, year after year? “The Maui magic,” as tournament director Nelson Taylor calls it? Perhaps it stems from the tournament’s unlikely origin: Chaminade’s impossible-to-believe 77-72 upset over No. 1 Virginia and Ralph Sampson in Dec. 1982. Those Cavaliers — who only swung through the Aloha State on their way home from a foreign tour in Japan — ended up on the wrong end of what Sports Illustrated’s Alexander Wolff deemed “the greatest upset never seen.” Not only did the Silverswords’ improbable win convince Chaminade (then an NAIA school) officials not to change the school’s name, but it gave life to an idea that then-Virginia coach Terry Holland allegedly pitched even before UVa’s famous defeat: Chaminade hosting a basketball showcase early each season.

Two years later, Holland’s concept came to life (although the tournament’s debut was actually played on the Big Island), and it found its long-term home in the Civic Center in 1987.

That building plays a role in amplifying the atmosphere. Up until 2003, the 2,400-person gym didn’t even have air conditioning — a novelty that, at times, even cost teams games. In 2001, Williams’ penultimate year at Kansas, the Jayhawks lost to Ball State in part because freshman guard Aaron Miles cramped up on KU’s final defensive possession. (Ball State beat UCLA in the semifinals the next day, in a run fondly remembered as the “Wowie in Maui.”)

Purdue won the 2023 Maui Invitational, which was moved to Honolulu. (Brian Spurlock / Icon Sportswire via AP)

The sheer quality of teams and coaches invited has also made the Maui Invitational into a mainstay. In 2018, when Zion Williamson-led Duke was the headliner, Taylor remembers fans hiding under the bleachers just for a glimpse. And you could practically fill an entire Hall of Fame wing with coaches who have cut down the Lahaina nets: Williams, Mike Krzyzewski, Rick Pitino, Jim Boeheim, Bill Self, Lute Olsen, Jim Calhoun, Mark Few, C.M. Newton, and countless others.

Michigan State coach Tom Izzo understands the tournament’s history better than most. His first game as the Spartans head coach — a two-point “blowout” over Chaminade, he jokes — came in the Civic Center, with Magic Johnson seated directly behind him. And while this is his fifth time back, he knows the circumstances make this year’s event one of one.

“Let’s face it: For a lot of people, their lives and their world changed,” Izzo said. “Are we going to be part of people feeling a little better? You don’t feel better when you lose something; you just hope that you get enough things that help you move forward, because unfortunately that’s the way the world is, and we have to move forward.”

There are thousands of these stories. Fuentes’ starts with smoke.

Fuentes smelled it, from inside his catering kitchen in downtown Lahaina, on the afternoon of Aug. 8, 2023: the day the fires began. “I went outside,” Fuentes said, “and the fire was pretty much at the corner.”

As official reports would later explain, the Lahaina fire — the most severe of the four separate wildfires that ravaged Maui — was, in many ways, the product of a perfect confluence of conditions: an ongoing drought, which turned the island’s natural terrain into “dry fuels”; gale force winds as strong as 80 miles per hour, a byproduct of nearby Hurricane Dora; downed power lines and bare electrical wires that sparked on contact; downhill geography that practically funneled the flames toward Lahaina; a “dense urban landscape,” which allowed the fire to spread via “radiant heating and flying embers”; and the ripple effect of a town turning to tinder, each fallen electric pole or exploding car becoming like another spark for an inferno that needed no assistance. Even water pipes were burned to nothing, preventing firefighters from tapping into much-needed hydrants.

The state’s electric utility, a school system and Maui County are among the parties that agreed to pay $4 billion to settle more than 600 lawsuits. A joint report by the state and the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) eventually classified the fires “accidental,” caused by the re-energization of broken utility lines.

When Fuentes saw the flames, he went into survival mode. He thought of his wife. His two sons. The life he’d built in Maui after moving there from Mexico as a 19-year-old with dreams of surfing and sun. “I wasn’t born here,” Fuentes said, “but I was reborn here.” Eventually, teenage freedom gave way to family, and a budding passion: cooking. A well-known local chef took Fuentes under his wing. Fuentes climbed the culinary ladder, until he was a top cook at The Ritz-Carlton in Kapalua. Eventually, he started his own business, Island Catering, which has fed Maui Invitational fans for years.

After Fuentes saw the flames, he tried driving out of Lahaina, but traffic — and the rapidly-spreading blaze — trapped him. He saw only one option: the ocean. He dove in, and treaded water as the town he’d come to call home slowly disintegrated to ash. Five hours passed. Six. Seven. He doesn’t remember exactly how long he swam — only that the next morning, at about five a.m., the fire department pulled him from the water.

He immediately thought of his family. His boys. Were they OK?

The fire department brought Fuentes to Maui Preparatory Academy, one of many evacuation sites. Fuentes practically jumped out of the car, desperately screaming his sons’ names.

Then he saw them: his son and his son’s girlfriend, heading straight to him.

“That was it for me,” Fuentes said. “The biggest gift ever.”

Fuentes lost his building, most of his business’ infrastructure, but he still considers himself among the lucky ones.

“I survived that fire,” he said, “but now I’ve got to survive life. So does my family, my employees. Everyone.”

That, for the past 15 months, has been Lahaina’s plight: sifting through the rubble — an estimated $5.5 billion in total damages — and trying to start anew.

Easier said than done. An estimated 2,170 acres burned in Lahaina alone. Over 3,000 structures — at least 1,350 of them residential — melted down to nothing. Power lines, toppled. Water and sewer systems, destroyed. Before last year’s Maui Invitational, Bilas and an ESPN camera crew swung through Lahaina and were permitted into the burn zone. Bilas remembers being told beforehand that it was like a bomb went off near Front Street, the main thoroughfare.

“There’s no bomb that would have done that much damage,” Bilas said. “It was leveled. … Everything was gone.”

“We’ll forever refer to our community,” said Maui mayor Richard Bissen, “as pre-fire and post-fire.” (Hiroto Sekiguchi, Jae C. Hong / AP)

Recovery efforts began immediately. Within two weeks, some 8,000 displaced locals relocated to nearby hotels in Ka’anapali, where they’d stay for several months. The college basketball community chipped in, too, raising $1.7 million as part of a Hoops for Ohana fundraiser. Coaches and schools sent in autographed merchandise to be auctioned off, tickets to games, anything they could to pour much-need dollars back into Maui.

Williams has been retired since 2021, but he’s back this week hosting a youth basketball tournament, which he said is the least he can do for a place he holds so dear.

“When I saw the fires and the buildings gone,” he said, “I thought of the people.”

The process is ongoing, but some 15 months later, those people are finally starting to see signs of progress. Last week, for the first time since the fires, a family who lost their house was able to move back into their rebuilt home, just in time for Thanksgiving. Sixty more dwellings are under construction, plus an 89-unit apartment building. About 250 construction permits have already been issued, with another 150 in the queue close to being approved. Even the landscape is slowly starting to come back; just across Front Street — which is still blocked off — beautiful pink-and-peach flowers can be seen growing out of piles of rubble.

So, as the tournament tips off Monday, what is tourism’s place amidst tragedy?

According to the Maui Economic Development Board, the industry directly or indirectly accounts for about 70 percent of the island’s revenue. The Maui Invitational is key to that; in 2022, the last year Lahaina hosted — it was also moved off-island in 2020 and 2021, due to COVID-19 — it yielded about $24 million in economic impact, according to Taylor. “Take that number over 40 years,” he said, “and that’s pretty significant.”

And necessary, more now than ever.

But that doesn’t mean some locals aren’t apprehensive, or unsure about hosting thousands while they themselves haven’t been able to return to their homes. Folks will enjoy Ka’anapali Beach, soak up the sun, while less than a mile away are the burned remnants of a community fundamentally changed forever.

“(Tourism) is something that has been in part beneficial — and in some parts, intrusive,” Bilas said. “It’s a profoundly difficult issue that goes beyond the basketball tournament.”

The Maui Invitational has tried meeting the issue head on, sending out a “Know Before You Go” document to any fans making the trek. So people are aware of the situation, and how to conduct themselves. How, as the notice said, to visit, “with aloha and empathy.”

“As we move forward, for our community to know those steps have been taken is really, really important,” Bissen said, “because it shows the partnership, the foresight that the tournament has.”

The college basketball community has played a role in raising funds for Maui’s recovery. (Marco Garcia / AP)

Taylor said fan demand this year — especially with UConn, the two-time defending national champs in town, plus high-profile brands like Memphis, Michigan State, and UNC — was so strong that, “if we had the ability to build another hotel between now and the first game, we would.” Ticket packages — including local-only specials — sold out in hours. More restaurants, even on the outskirts of Lahaina, have re-opened in anticipation of the wave this week will bring. And over the weekend, the community held its Lahaina Festival, where local vendors could sell their wares.

“We’re not just returning a basketball tournament,” Bissen said. “We’re trying to return our community to some sense of normalcy, and something they can feel good about.”

When the Maui Invitational asked Fuentes to cater again this year, he was overjoyed. He’s kept some of his food trucks running the past 15 months — even if his employee count has dropped from 22 pre-fire to only four today. The economic boost from the tournament will be unlike anything he’s known since August 2023. Between the Maui Invitational returning and reopening his first brick-and-mortar shop — a noodle bar — in December, Fuentes has hope again. Maybe he can rehire some of his former employees. Continue expanding.

“It’s a little light at the end of a dark, whole yearlong tunnel,” Fuentes said. “That’s answers for prayers. … It’s life.”

(Top image: Kelsea Petersen / The Athletic; Photos: Lindsey Wasson, Ty O’Neil, Mengshin Lin / Associated Press