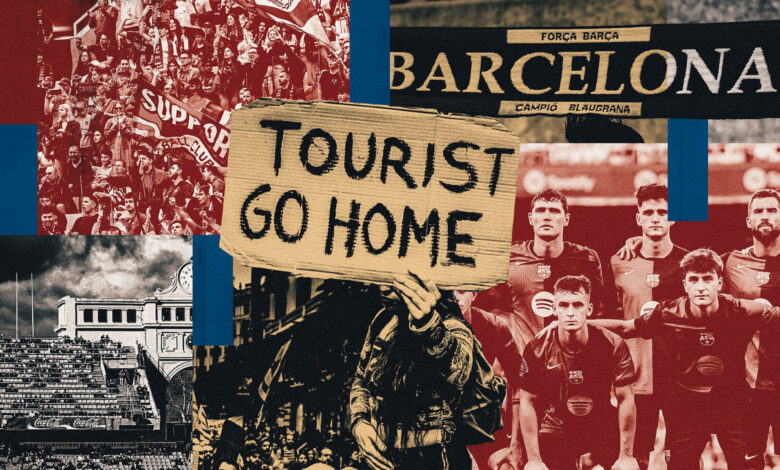

Barcelona, mass tourism and the protests targeting foreign visitors

If you’ve visited Barcelona recently, you may have noticed something unusual.

Since the beginning of the summer, central hotspots such as La Rambla and neighborhoods such as Gracia and Parc Guell have been covered in graffiti with the words “Tourists go home”. It is all part of the same picture. The people of Barcelona are protesting against mass tourism.

On July 6, a demonstration was held in which (according to the organizers) between 10,000 and 15,000 people took to the streets (the police estimate the number at around 3,000). Some even targeted individual tourists, spraying them with water pistols while they were drinking coffee or having lunch, and cordoning off hotels and restaurants with red tape as they “reclaimed” territory for themselves.

It brought international attention to an issue that had been on the minds of many residents for years. Now, with a consolidated movement of awareness and action, Barcelona’s politics and daily life are beginning to reflect this new perspective — and the city’s most famous football club is watching with interest.

Barcelona starts each season with a home match for the Joan Gamper Trophy. The tradition dates back to the mid-1960s and pays tribute to Gamper, one of the club’s founders in 1899.

The match is always played in early August, so there are many foreigners in attendance. This year, Monaco were the guests (and they beat Barca 3-0 — though any qualms about that result have been forgotten in Barca’s strong start to the new league season).

On the way to Barça’s temporary home on Montjuïc (they have been playing at the Estadi Olimpic Lluis Companys since the start of last season while extensive renovations are carried out at the Camp Nou), leaving from Plaza Espana and using the escalators that help you reach the stadium, several tourists spoke to The Athletics about their experiences in the city.

Stuart, a 34-year-old from England, said he felt tourists were being treated “unfairly”. He said he “understood the anger and frustration of residents” but felt it was being “handled wrongly” because “the problem is with the government and they need to find a solution”.

Another was Giulia, a 34-year-old Italian who has lived in Barcelona for several years.

“When I first saw the graffiti, I felt unwelcome,” she said. “But I understand why people are upset, because I am too.

“There are always drunk people, usually from England or Germany, shouting without their shirts on. Would you go out on the street like that in your own city? This is not Disneyland. People live here.”

Street graffiti in Barcelona – Guiri is an informal term for a badly behaved or annoying tourist (Paco Freire/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Marti Cuso was involved in organising the demonstrations through his role in a residents’ association representing Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter, a central area of the city that is very popular with tourists.

“The party responsible is not the tourist who comes to Barcelona and wants to see a Barca match,” he says. “The party responsible is the entire economic system.

“What we have been denouncing for years is the ‘tourist’ economy. Tourism has a very strong negative impact on the lives of residents. It leads to housing shortages with apartments being converted into holiday homes, rising prices, degradation of heritage, pollution and the erosion of labour rights. A change must be proposed to reduce the weight of tourism in the city’s economy.

“Flight prices are going up and low-cost airlines are going to disappear. If oil becomes scarce in 20 or 30 years, what will happen to international mobility? We have a city that depends on 30 million visitors. We need to generate economic alternatives and do it in a planned way.

“The graffiti alone does not help people understand this, although it has certainly contributed to the mediatization of the problem. But some people take it very personally, as if we are attacking them. The least you ask of the tourist is that they know that there is a conflict with this, but you should never directly point them in the wrong.”

Tourists get caught up in the July 6 protest in Barcelona (Josep Lago/AFP via Getty Images)

Tourism is extremely important to Barca. There are many other reasons to visit Barcelona — the food, the climate, the architecture, the art and the beaches — but for many who come here, the world-famous football club is also high on the to-do list.

Barca’s museum is the most visited in Catalonia and the third most visited in Spain, sources at the club — who, like all the people mentioned here, preferred to speak anonymously to protect relationships — said The Athletics that on average 52 percent of match tickets are sold to people from outside Spain. During their most recent season at Camp Nou (2022-23), their ticket revenue was €71.6 million (£60.3 million; $79.3 million at current rates), of which €37.3 million came from tickets sold to tourists. All of which made the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic particularly devastating.

GALLING DEEPER

Crisis clubs: Barcelona – from failure to comeback in just two years

The importance of tourism for Barca has already caused some tension among the club’s fans. Last season, they introduced a new policy that penalized season ticket holders who did not release their seats for resale if they were unable to attend a match. This did not go down well with some of Barca’s ‘socios’ (club members). For the 2023-24 season, only 17,552 of the 80,274 season ticket holders at Camp Nou decided to take seats at Lluis Companys.

Protesters in Barcelona – demonstrations also took place in other parts of Spain (Paco Freire/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Barcelona City Council has already announced steps in response to the increasing pressure on mass tourism.

“Our will and commitment to limit the massive flow of tourists and its consequences for the city are firm,” said Mayor Jaume Collboni (of the Spanish Socialist Party) after the demonstration in July.

A month earlier, Collboni spoke of plans to close more than 10,000 short-term vacation rentals, such as those available on Airbnb, by November 2028 and return them to residential use. Limiting tour groups to 20 people, raising the tourist tax to €4 per night and creating a specific plan to manage high-traffic locations, such as the area around the Sagrada Familia, are other measures in the works.

Barca sources say the club is closely monitoring the situation surrounding recent protests, saying they feel affected by negative news that could discourage a tourist from travelling to the city.

Cuso and the residents’ association he represents are sceptical on two counts. First, they believe that the measures outlined by local politicians do not go far enough (and they also suggest that some may not be feasible, given that the next municipal elections are scheduled for 2027). Second, they do not believe that the recent protests and graffiti will have a lasting effect on the number of people choosing to come to Barcelona.

“Nobody is going to stop coming because of four water pistols,” Cuso says. “The Spanish and foreign media are generating a discourse of fear and it is something that responds to the desire to discredit the protests and their underlying arguments.”

But he is especially concerned about the impact of mass tourism on Barça fans.

Eintracht Frankfurt celebrates victory over Barça in April 2022 (David S. Bustamante/Soccrates/Getty Images)

On April 14, 2022, Eintracht Frankfurt visited Barca in the return leg of their Europa League quarter-final. The visiting fans were officially given 5,000 tickets. In the end, around 30,000 supporters from Germany came to the stadium — the total attendance was 79,468.

It was a huge embarrassment for Barca. Since then, measures have been taken to prevent a repeat, such as blocking online ticket sales from foreign IP addresses on European matchdays, or not allowing rival colours to be worn in sections reserved for home fans.

More recently, speaking ahead of last weekend’s La Liga match between Barcelona and Athletic Bilbao at Montjuic, visiting manager Ernesto Valverde was asked what kind of atmosphere he expected. He replied: “It’s summer, there will be a lot of tourists, so I don’t expect anything special.”

Cuso associates this with the broader trend of too much tourism.

“If you watch a Barca game now, you have someone different next to you every day, someone who doesn’t know the chants and who is more interested in taking photos and recording reels for Instagram than in the game itself. This completely depersonalizes the experience and betrays the whole identity of what it was like to go to the Camp Nou in the 90s or 2000s.

“The club has clearly positioned itself as a global brand and is playing this game. But Barca is not a company, even if it behaves like one. They are an exception in the world of football (because it is one of many owned by its members). Now, in the Camp Nou reform, they are adding more VIP boxes and lounges, which will certainly cost thousands of euros. This is the model that everything is moving towards.”

The new Camp Nou will have a capacity of 105,000. The stadium isn’t expected to be fully completed until the summer of 2026, but Barca are expected to return before the end of the year with a reduced capacity of 64,000 – although they say they can’t guarantee an exact timeframe.

An increased capacity should be good news for the many thousands of people on the waiting list for season tickets, but sources at Barça say no final decision has been made on how many extra players will be made available.

But one idea is to reserve a portion for general ticket sales, again keeping the city’s tourists firmly in mind.

(Top photo: Getty Images. Visual design by Eamonn Dalton)