Baseball History Is No Longer Made With Ash Bats (Published 2022)

CLINTON TOWNSHIP, NJ — On a beautiful fall afternoon, Rosa Yoo pulled off the road at the Round Valley Recreation Area and dived into the woods to perform the grimmest task of her job as a New Jersey Forest Service health expert: the status of check the white ash trees.

She came to a clearing, where a forest of ghostly gray husks cut ghostly figures among the colorful foliage. As she suspected, the trees whose canopies had painted the landscape gold and maroon a year ago were dead or dying.

“There are dead ash trees everywhere,” Yoo said. “It’s hard to find an ash tree anywhere that isn’t affected.”

She means the species is infected with an invasive insect called the emerald ash borer. This has been torturing North America for years, leaving behind huge areas of dead forest.

Among native tree species, the ash represents a small portion of continental forests. But there is one arena where the ash has historically ruled: baseball.

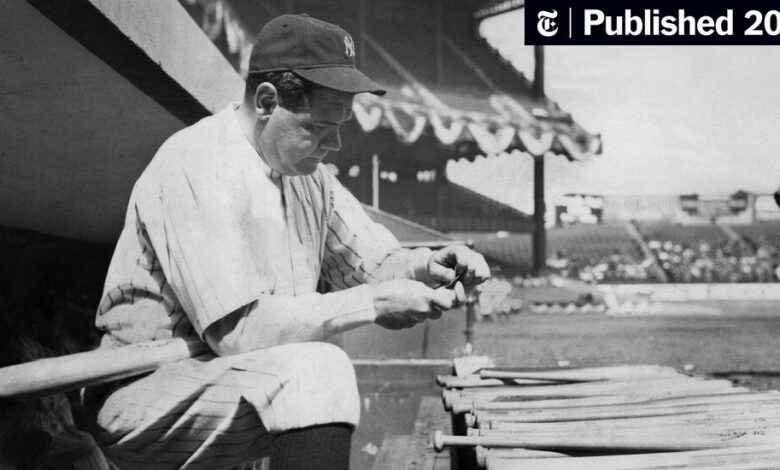

Much of baseball history was written with ash bats, from Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak in 1941 to Roger Maris’ 61 home runs in 1961 to Mark McGwire’s 70 home runs in 1998.

Babe Ruth swung ash bats weighing 16 ounces. Ty Cobb had his made for him by a box maker. Ted Williams used to travel to the factory of Hillerich & Bradsby, maker of the Louisville Slugger, to select the wood he wanted to carve into his bats.

Today, however, the ash tree is virtually extinct in baseball, as the trees are threatened by extinction by beetles. This postseason, which runs from early October to early November and began with 12 teams and more than 300 players, may be the first in generations that does not record a single at-bat with an ash bat.

In 2001, Hillerich & Bradsby produced approximately 800,000 ash bats per year, many of which went to dozens of major leaguers. Today, the company has just one Ash fan: Evan Longoria of the San Francisco Giants, whose team didn’t make the postseason.

It’s like all Major League Baseball stadiums suddenly stopped selling hot dogs. When Jack Marucci started making bats for his son in a backyard shed in the early 2000s, the wood he picked up at the lumber yard was ashes. Because what else would he choose?

“That was the main ingredient,” Marucci said. “I only knew ash bats.”

The company he founded, Marucci Sports, and its sister brand Victus, now make bats for more than half the players in the major leagues. Only five Marucci clients asked for ashes this season: Joey Votto, Javier Báez, Kevin Plawecki, Tim Beckham and Kiké Hernández, none of whom made the playoffs.

There could be a handful of others, like Brad Miller of the Texas Rangers. But Aaron Judge’s 62 home runs for the Yankees this season came from the barrel of a maple bat.

Pete Tucci, the founder of Tucci Limited in Norwalk, Conn., was looking through his logs, trying to find the latest customer who came to him looking for ash bats.

“It was Omar Narváez,” Tucci said, referring to the Milwaukee Brewers catcher. “He ordered six ash bats during spring training in 2020.”

And that was it.

The transformation has not gone unnoticed. Tucci was a former first-round draft pick of the Toronto Blue Jays in 1996 and swung exclusively with ash bats during his career. He tried maple, which was gaining traction in the late 1990s. He didn’t like it.

“I kept trying because other guys liked it,” Tucci said. “But I would always go back to ash.”

Baseball hitters are legendarily intuitive, and Tucci was no different. Because ash is a softer wood, with a looser grain structure, it can be more susceptible to splintering or peeling. But in the barrel, the so-called sweet spot, the softer ash bats can flex on contact, creating a “trampoline” effect on the ball.

“The grain creates a kind of groove,” Tucci said. “I felt like that groove caught the ball a little more and produced more backspin. I felt like I got more performance out of an ash bat than a maple bat.”

When he started making bats in 2009, it was a different story. Joe Carter was the first high-profile star to experiment with a maple bat, back in the 1990s. But after Barry Bonds hit 73 home runs in 2001 with a maple Sam Bat made by the Original Maple Bat Corporation, a Canadian company, dozens of others followed suit, opting for the hard-yet-light combination of maple.

It’s also a good thing. Because just as maple was gaining popularity, quality ash wood – with its beneficial eight to twelve growth rings per inch – became more difficult to obtain.

At the state park in New Jersey, Yoo drove her ax into one of the dying ash remains. She peeled off a pancake-sized piece of bark as if it were Velcro.

“That shouldn’t happen,” Yoo said.

The emerald ash borer is the size of a grain of rice. But it swarms through the forest, penetrating the protective bark of ash trees. It lays eggs in the cambium layer, which the larvae eventually feed on, sapping the tree of essential nutrients from within. Once sated, the winged insects burst out of the tree, starting the cycle anew.

Since the borers were first discovered in the United States in 2002, in Michigan, efforts have been made to stop or slow their progress. But they have been spotted as far north as Winnipeg, Manitoba and as far south as Texas. This summer, they were discovered in Oregon.

More recently, Yoo has assisted in the New Jersey Department of Agriculture’s efforts to implement biological control, releasing parasitic wasps known to feed on emerald ash borer larvae. But it will take years before the predators are in the numbers required to fight back against the borer, which is native to Asia and most likely hitched a ride to the United States on a container ship.

Meanwhile, the trees are dying.

“Nature has a very resilient way of holding on there,” Yoo said. “I believe there will still be ash, but it will take a long time before it can get back to where it was.”

Bobby Hillerich, a fourth-generation batmaker for Hillerich & Bradsby, admitted the company was late in fully realizing the impact. Louisville Slugger began using ash and hickory in 1884, a heavier wood that fell out of favor in the 1940s.

For more than a century, Hillerich & Bradsby sourced its ash lumber from mills throughout Pennsylvania’s densely forested northern reaches and New York’s southern border. The forests provided such abundance that 40,000 trees could be cut per year to make Louisville Sluggers, at a cost of just 90 cents per board foot.

“We had this fantasy that it would be controllable,” Hillerich said of the insect infestation. “It was probably a few years later that we realized this wasn’t going the way we thought.”

The company still produces 325,000 to 350,000 ash bats a year, Hillerich said, but those are the cheapest units customers can find at a local retailer.

“They’re mostly used for protection,” Hillerich said, “or for Halloween costumes.”

Regardless of the borer, Hillerich thinks maple would still have been the most popular wood for major leaguers because of its strength and consistency. But demand for ash likely would have remained strong, he said, if batmakers had been able to maintain their supply.

“We had to have some tough conversations with some guys,” Hillerich said. “We said we couldn’t be sure of the ash delivery we got. We just can’t guarantee it was the quality wood they swung.”

Birch is another species that has gained a foothold in the emptiness of the ash. But it has its faults too.

“Players don’t like the sound,” Hillerich said.

Jason Grabosky, the director of the Rutgers Urban Forestry Program, is more optimistic than most about the future of ash trees in North America. Because they can shed seeds in large quantities, a new generation of ash trees can still take root after the borer has destroyed the old one.

For baseball, however, it’s the end of an era.

“It will probably be at least a generation before we see ash bats come back,” Grabosky said. “But if we’re going to let kids play baseball, I think we still want ash bats.”