How dare you say woman! New woke bible for midwives urges use of terms like ‘surrogate mother’

A new guide for doctors advises using terms such as “breastfeeding” and “pregnant person” to meet patients’ needs.

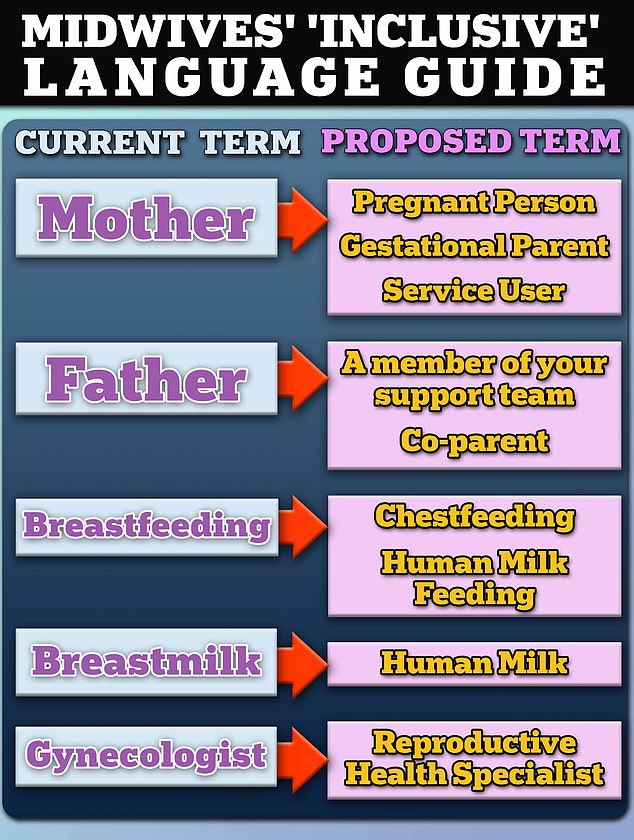

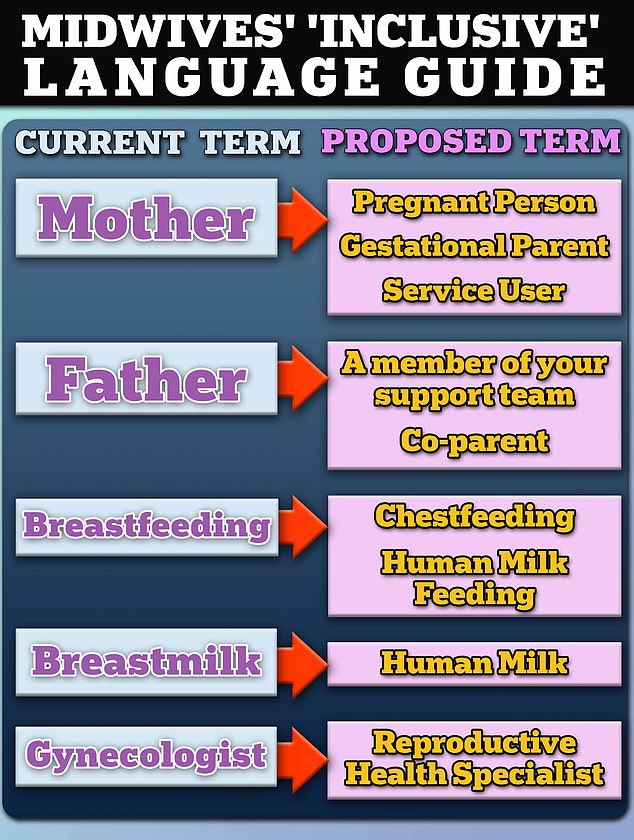

Midwives and gynaecologists should replace the words ‘breastfeeding’ and ‘mother’ with terms such as ‘surrogate mother’ or ‘pregnant person’, according to guidelines published in a new report.

Additionally, “father” should stand for “a member of your support team.”

And instead of breast milk, the group recommends “breast milk” or “nursing parent’s milk.”

That’s according to a progressive group of midwives and academics from the US, UK and Australia, who claim that dozens of terms related to parenting and childbirth should be replaced with more ‘inclusive’ words.

New guide suggests replacing breastfeeding with ‘breastfeeding’ to be more inclusive

The guide, which was released in May and published in the magazine Birth: Issues in perinatal careis not a legally binding set of rules, but a recommendation for healthcare providers.

The group wrote: ‘We emphasize that midwifery has the opportunity to be effective in advocating for human and reproductive rights for all by embracing inclusive language that reflects its intersectional commitment to reproductive justice.

‘Ultimately, midwifery has an ethical obligation and opportunity to lead in gender decolonization and reproductive justice through the use of inclusive language.’

Midwives and gynecologists are both experts in prenatal care. However, midwives are not doctors, and the scope of their duties varies by state.

This guide is far from the only one to propose gender-neutral changes like this. Others published in recent years have recommended terms like “chesticles” for breasts and “d*cklets” for clitorises.

However, medical experts say such language can do more harm than good by “dehumanizing” mothers and creating unrealistic expectations for trans parents.

To support their case for the more ‘inclusive’ language, the group cited a case study of a patient named Sam, a transgender man with abdominal pain that tested positive on a home pregnancy test.

Sam told hospital staff he was a transgender man, but health care providers failed to recognize he had gone into preterm labor “due to systems, biases, and stereotypes surrounding his gender presentation and identity,” such as the assumption that he was not pregnant or could not sustain a pregnancy.

Sam’s baby died of umbilical cord prolapse, which occurs when the umbilical cord falls out of the uterus before the fetus, cutting off the fetus’s blood supply.

The researchers suggested that if Sam’s care had been focused on the fact that he still had female reproductive organs and could carry a pregnancy, doctors may have been able to detect the umbilical cord prolapse in time and prevent the death of the fetus.

But the assumption that only “women” could sustain a pregnancy harmed Sam and his fetus.

The authors concluded that in settings where traditional gender roles are reinforced and alternative options are not addressed, patient health outcomes are poorer.

Meanwhile, a study was published in the journal in 2022 Frontiers in Global Women’s Health so-called ‘gender-specific’ language such as ‘mother’ is crucial to avoid confusion in situations such as childbirth.

The researchers wrote: ‘The castration of female reproductive language has been done with the aim of meeting individual needs and making it as beneficial, friendly and inclusive as possible.

‘Yet this kindness has had unintended consequences that have serious implications for women and children.

‘Women have unique experiences, needs and rights regarding pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding that are not shared with others. It cannot be assumed that a woman’s interests will coincide with those of her husband or partner.’

The team opposing the new guide argued that nearly 4 million babies die each year worldwide and that the US has the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world. Therefore, “the best interests of the child come first” and using clear language is essential to reducing the number of deaths.

However, the midwives argued that because midwifery is a traditionally female profession, it is their duty to promote language as ‘a manifestation of feminism in action’.

To make the term more inclusive, they propose replacing the term “gynaecologist” with “reproductive health specialist,” as the term is derived from “gyneco,” which means “woman” in Greek.

Last year, trans woman Mika Minio-Paluello came under fire after she posted a photo of herself breastfeeding her baby on a bus

In 2018, the editors of the magazine Advances in neonatal care proposed similar changes. Namely, they said they would no longer publish articles using the words “breast milk.”

Instead, the words ‘breast milk’, ‘mother’s milk’, ‘father’s milk’ or ‘donor breast milk’ are now preferred.

And, the editors continued, “It is also preferable to use the word ‘lactation’ rather than ‘breastfeeding’ whenever possible.”

While the NIH style guide states that “breastfeeding” should be an option when discussing breastfeeding, it also adds that “breastfeeding shall not replace the word breastfeeding.”

Critics have suggested that replacing “breastfeeding” with “nursing” or “breast milk” with “mother’s milk” could create unrealistic expectations for trans women who are physically unable to breastfeed.

In other proposals for more inclusive language, Dr. Ilana Sherer, a California pediatrician, suggested that doctors call the vagina a “front hole” and the penis an “outie.”

During a presentation at the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) National Conference and Exhibition in October, she suggested calling breasts “chest” or “chesticles.” For male anatomy, Dr. Sherer suggested pediatricians call the penis “outie,” “junk,” “strapless” or “bits.”

Her suggestions, made during a workshop titled ‘Discussing Gender and Sexuality in Primary Care’, also included referring to the vagina as an ‘innie’, ‘front hole’ or ‘T-penis’ and the clitoris as a ‘dick’ or ‘d*ck’.

Despite urging, doctors have previously warned against politicizing medical language, saying it could confuse public health messages, especially for people whose first language is not English.