How SLAM magazine went from NBA ‘outcast’ to a Hall of Fame publication in 30 years

At a recent celebration, members of SLAM magazine’s staff, past and present over the last 30-plus years, couldn’t believe it.

The Hall of Fame. Really? SLAM in the Hall of Fame?

Founder Dennis Page and the publication were honored by the James Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame with the Curt Gowdy Transformative Media Award during a ceremony in August. To some, this seemed impossible back in May 1994, when the first issue — featuring Larry Johnson on the cover — was released.

Thirty years ago, SLAM was unlike anything in modern journalism. It didn’t play by traditional rules. Profanity in publication was not off-limits. The writers and editors didn’t pretend to be impartial.

“‘Outcast’ is a good word for us,” said Tony Gervino, the magazine’s first editor-in-chief who now works at Tidal as executive vice president and editor-in-chief.

SLAM was part of a culture shift that personified a time when the NBA was changing, a time when hip-hop began crafting the style of many players. The shorts were longer and baggier. Pregame music playlists were more likely to include Wu-Tang Clan or Snoop Dogg instead of R&B crooners like Jeffrey Osborne or Luther Vandross. Tattoos became as common as high-top shoes.

And there was SLAM, something of a disruptor itself by championing the voice of the fan. Inspired by hip-hop magazine The Source, SLAM’s vibrant photography and style of storytelling connected with a younger audience that cared about the shoes players wore just as much as the final score of games.

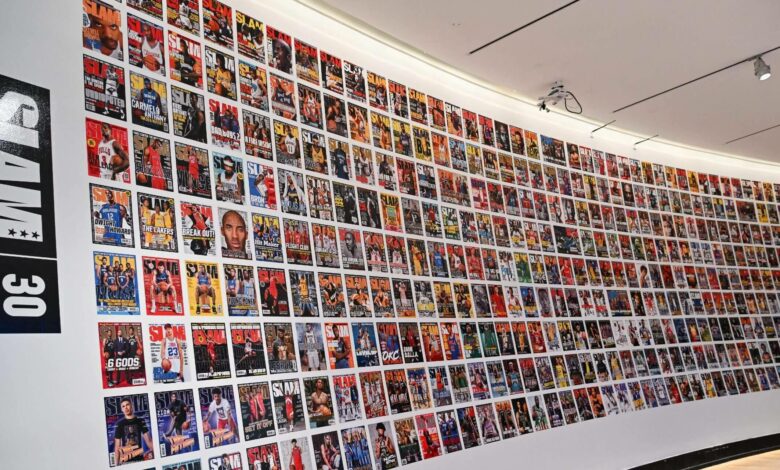

The result? More than 300 million magazines have been sold since 1994. There have been 132 covers to feature a Hall of Famer.

SLAM magazine’s production stats are showcased at the 30th anniversary exhibit at the James Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. (Bob Blanchard / SLAM)

SLAM didn’t act like traditional media — nor did it want to be. It resonated so much that others eventually tried to emulate it. It was quite the shift, considering early on the New York City publication had trouble getting media credentials for NBA coverage.

“We were really on the outside of the party looking in, and we just told people the party sucked,” Gervino said. “That’s why we were on the outside. We got into it, then we sort of roughed it up a bit.”

Page, in addition to being a big sports fan, has a huge appreciation for music. He was the publisher of Guitar World magazine when he became impressed at how The Source had captured the attention of the hip-hop generation.

Page believed the world didn’t need another magazine focused on rap, as there were plenty on the market. What he hadn’t seen was a publication that merged culture and sports.

“There were people all over the world, young kids that were into hip-hop, into basketball,” Page said. “But Sports Illustrated, Street & Smith didn’t speak to them. When we came out, we spoke to them.”

Fans accepted SLAM — and then the players became fans. The magazine covers became popular. Whether it was Kevin Garnett and Stephon Marbury showcasing their lavish jewelry or Allen Iverson getting featured in his Sixers jersey with his hair in an Afro rather than his usual braids, SLAM struck a nerve.

“We were just living it, and we wrote about basketball and referred to hip-hop music and lyrics. This was who we were,” Page said. “We weren’t a corporate publishing house, so we were just writing the magazine for ourselves.

“Honestly, I had no idea there were that many people in the world that would understand this and accept it and really appreciate it.”

Thirty years after its introduction, SLAM was honored with one of basketball’s most prestigious media awards. Success, however, might not have worked without the freedom the staff was given. That meant nontraditional journalism tactics such as giving space to the sneaker world, featuring player diaries and serving as a means to connect basketball fans globally before the internet.

It led to engaging content.

“First of all, we didn’t know any better,” said former SLAM writer and editor Lang Whitaker, who has worked for the NBA and GQ magazine and currently works for the Memphis Grizzlies. “We were just making stuff that we thought was cool, and I think that’s why it resonated.

“For better or worse, there wasn’t a lot of oversight. Nobody was telling us what to be like. Dennis just let us do our thing and let us kind of rock.”

No writer personified the SLAM style in its early days more than Robert “Scoop” Jackson.

“The most important person in SLAM history is Scoop,” Gervino said. “He literally launched a generation of writers and kids who said, ‘I can do that now.’”

Robert “Scoop” Jackson was one of the most respected journalists during SLAM’s early days. (David Zalubowski / Associated Press)

Jackson’s distinctive style of reporting allowed him to connect with NBA players in a way that was different yet welcomed. The Chicago native was closer to the players’ ages, and he had an eye for talent and trends. He wrote about Iverson being the future of basketball before he was in the NBA after watching Iverson play in a summer league while still at Georgetown.

Jackson, who is now a columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times, wanted to tell in-depth stories. He wanted to write about Chicago’s Ben Wilson, the Simeon High School prospect regarded as the top high school player in America who was shot and died in November 1984.

Editors at SLAM weren’t familiar with Wilson’s story. That gave Jackson more urgency to tell it — even if it happened nearly 10 years after Wilson’s death.

“We did a human interest story that was rooted in the culture of basketball and what the future of basketball could have been,” Jackson said. “But that future of basketball never got a chance to live. To me, once you go there, that’s the foundation of how you’re going to deal with telling the story about the culture of basketball.”

Jackson was a staple at SLAM for 11 years. Though an NBA presence often made the cover of most issues, stories like Wilson’s were the soul of the publication.

“Tony and I looked at Dennis as that White guy who really understood Black culture,” Jackson said. “He understood the game of basketball wasn’t just about the NBA.”

That mindset led SLAM to take a chance on writing about Iverson before he made it to the NBA. It also allowed them to lean more into writing about the culture and lifestyle of those in basketball, such as the story of streetball legend Rafer Alston, who, while at Fresno State, was featured in the magazine as “The Best Point Guard in the World.” It also meant finding high school standouts and profiling women who were stars in the game.

One story Jackson fondly recalls is a 1997 profile of Dawn Staley, the former star point guard at Virginia, six-time WNBA All-Star and three-time Olympic gold medalist who now is the coach of the reigning women’s college basketball champion South Carolina Gamecocks. Jackson simply hung out with her in her native Philadelphia, visiting her old neighborhood and the courts she played on while learning more about her as a person.

This piece wasn’t about Staley’s time with Team USA, and the WNBA hadn’t officially started (the first WNBA game took place June 21, 1997). Instead, the story was about the men she played against growing up and what the city of Philadelphia meant to her.

“It had nothing to do with her professional career, nothing to do really with what she did at Virginia,” Jackson said. “We told the ’hood story of Dawn Staley.”

The importance of Iverson cannot be understated. Jackson said he and Page disagreed on what to do with Iverson. At the time, a non-NBA player had not graced the cover. Iverson still was at Georgetown but had won Big East Defensive Player of the Year as a freshman while averaging 20.4 points.

A lot of basketball fans weren’t familiar with Iverson as a player. Some had heard about him as a prep star who was arrested during a fight at a bowling alley. Jackson believed it was important to write about who Iverson was and his basketball journey, not just what had made headlines off the court.

“Part of the foundation of our responsibility was telling the cultural side of basketball first, and then can it connect to the NBA second,” Jackson said. “But it wasn’t just Iverson. Even though his name gave it prominence, it was us doing the story.”

Jackson said Michael Jordan was also important to SLAM. Page wanted Jordan to be on the cover of the first edition, but he retired after the 1993 season. Instead, the cover went to Johnson.

Jackson said SLAM covered Jordan’s return to the league based on what he meant to the culture of basketball. It also helped that Jordan wasn’t fond of Sports Illustrated, which had famously used its cover to tell him to give up playing baseball.

Jordan opened up to Ahmad Rashad from NBC, but the network was still part of the NBA’s media machine.

“We were told Jordan stories differently than anybody else. None of our Jordan stories were like anything anybody else was writing,” Jackson said. “We were able to build a relationship with him, and he felt comfortable with us in a way that he didn’t feel with anybody else.

“We talked to him about things dealing with just his approach to the game of basketball and his contribution to the game of basketball from a cultural perspective. So, I think that carried as much weight as our journalistic relationship with Allen Iverson.”

Jordan’s first SLAM cover was in July 1995. He ended up doing 13 covers in the magazine’s 30 years — including three of the first 19 issues.

Hip-hop was a little more than 20 years old at the time, and by the 1990s, it was playing by its own rules. From fashion to subject matter, the music pushed a new culture forward.

The writers at SLAM did the same. Page credits Jackson for being a big part of SLAM’s emergence. Jackson was a young Black writer in locker rooms, and for some players, that wasn’t the norm. Like many of the players he covered, Jackson was a part of a generation that grew up on hip-hop, and he was interested in telling players’ stories in a different way.

“He was a young, great writer, and he understood (the players) as a person,” Page said. “We were inside out as opposed to trying to be objective, passing judgment, which journalism can do. We were kind of one of them. It’s really not that complicated or that deep, looking back.”

SLAM’s culture was heightened with the assistance of visuals.

The magazine has produced some of the most unforgettable cover photos in basketball. One reason the magazine is still printed is the covers that become T-shirts. Page said SLAM had a deal with clothing brand Mitchell & Ness that allowed it to make T-shirts out of certain magazine covers.

The covers, many with hip-hop references, were memorable for players. NBA Hall of Famer Shaquille O’Neal said he doesn’t remember all the SLAM covers he was featured in, but when shown a few, one caught his attention.

“I remember that one,” he said, identifying the September 2000 issue that had “Victorious BIG” in the background. It celebrated O’Neal’s first championship with the Los Angeles Lakers.

The basketball connection is clear, but the title also is a play off the name of one of O’Neal’s favorite rappers: The Notorious B.I.G.

“This one is my favorite,” he said.

SLAM didn’t turn to traditional basketball photographers for its covers. It went to professionals like Atiba Jefferson, who has a background in skateboarding. It also went to Jonathan Mannion, who made his name as a photographer in the music industry.

Mannion has shot album covers for several hip-hop and R&B stars, including Jay-Z, DMX, DJ Khaled, Lil Wayne, Rick Ross, E-40 and Aaliyah. Working with SLAM was a new test, but a welcomed one.

“As far as execution, they really set me free,” Mannion said. “I loved working with this level of athletes. … I always kind of enjoyed (SLAM shoots), but I was there to tell an authentic story, too.”

One of those opportunities was shooting Chamique Holdsclaw when she was a star at the University of Tennessee. Holdsclaw was the first woman to grace the cover of SLAM.

Holdsclaw became a fan of the magazine as a preps star at Christ the King High School in New York. After she dominated the college circuit, SLAM asked her whether she would be the first woman to play in the NBA.

The Tennessee standout then was told to return to New York, where Mannion — whom she dubbed “the Hip-Hop Photographer” — would be behind the camera.

Holdsclaw’s groundbreaking cover — her wearing a New York Knicks uniform for SLAM’s September 1998 issue — is one she’s still asked to autograph.

“(When) I got there, it was, like, the dopest photo shoot that I’ve ever done,” Holdsclaw said. “Jonathan was just coming up with ideas. He was like, ‘They want you to wear this.’”

Holdsclaw’s cover and photo shoot captured so much that defined SLAM. It was edgy and forward-thinking. Even her stance and gear were hip-hop in style.

“I looked at that Knicks jersey, and I was like, ‘Oh, this is good,’” she said.

One of SLAM’s most popular covers is the Class of 1996 double cover that featured rookies from the ’96 NBA Draft class. Future Hall of Famers Kobe Bryant, Ray Allen and Steve Nash are part of that crew, along with future All-Stars like Marbury and Shareef Abdur-Rahim.

Former Syracuse star John Wallace was a rookie with the Knicks during the 1996-97 NBA season. He said that class, highlighted by Iverson and Bryant, brought a hip-hop mindset to the NBA.

“You always hear this narrative: Rappers want to be basketball players; basketball players want to be rappers,” Wallace said. “But that was because of us and our era, what we ushered in. They weren’t saying that about the Michael Jordan (era) guys. They weren’t listening to rap and hip-hop like we were.”

Ben Osborne worked at SLAM for more than 18 years, the last 10 as editor-in-chief. He said the importance of sneakers in SLAM’s staying power cannot be overstated. It’s now common for shoes to receive media attention. That wasn’t always the case.

Shoe companies recognized that, too. Their support via ads helped keep things afloat. Reebok and Foot Locker were among the early companies that supported with advertising.

SLAM eventually would dedicate entire issues to shoes, KICKS. Now, some journalists exclusively cover shoes.

“We knew the biggest sneaker companies in the world were going to support an issue every single month,” Osborne said. “That just took a little bit of weight off. They weren’t starting from scratch every month to get people to support it. I think that, that made us cover sneakers more. Fans liked that even more because we were doing it differently than other places.”

SLAM has evolved in the social media era by continuing to lean into culture. Fashion is a big part of that. SLAM has an Instagram account, LeagueFits, which has more than 1 million followers.

SLAM has seen significant growth in its 30 years of existence. The Hall of Fame exhibit serves as proof. (Bob Blanchard / SLAM)

Adam Figman started at SLAM as an intern in 2010. He’s now a former editor-in-chief and chief content officer who took over as the company’s CEO in April. He said the social media accounts and the cover T-shirts have been key in keeping the magazine’s place in the basketball culture.

Even as players post their own photos on social media, something still resonates with them about a cover shoot for a magazine. For players like Holdsclaw, Cooper Flagg and Zion Williamson, appearing in SLAM as prep phenoms is different.

“Everyone wants to be on a cover, because anyone can post a photo of themselves,” Figman said. “Any basketball player can say, ‘Here’s what I look like. Here’s a cool photo of me.’ But a cover is a special moment. It’s a stamp, and a SLAM stamp, to me, is validation. We only do so many covers, so it means something special.”

SLAM’s recognition by the Hall of Fame is an accomplishment for all who worked on the magazine. It’s an honor that shows how impactful SLAM has been. All say the moment remains surreal.

In the end, the outcasts were invited to the party. And they will be recognized by partygoers at the Hall of Fame forever.

(Top photo: Bob Blanchard / SLAM)