How tattoos can increase the risk of cancer, doctors reveal – while experts warn the specific color may be more harmful

When doctors in Australia discovered a hard mass in the breast of a 36-year-old woman known to have genetic risk factors for cancer, they immediately performed a biopsy, fearing she had an aggressive tumor.

But tests soon showed it wasn’t cancer. It was a blob of tattoo ink — the patient was heavily tattooed and some of the ink had collected in a gland in the chest, mimicking the appearance of a tumor, the surgeons reported in a medical journal in 2022.

In a second, very similar case – this time involving a 50-year-old woman – described in the Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology in June, a suspected cancerous tumor turned out to be hardened tattoo ink.

Twenty years ago, only 16 percent of adults in Britain had a tattoo. Today that figure is almost 30 percent, as body art, once largely reserved for sailors, bikers and rock stars, has gone mainstream.

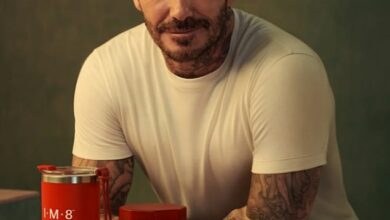

David Beckham shows off his collection of tattoos, built up over the years

Now everyone from English football legend David Beckham to Princess Eugenie has embraced the inked skin.

But while the vast majority of people with tattoos experience few or no significant side effects, they are certainly not without risk. Well-documented side effects range from photosensitivity (where tattooed skin becomes more sensitive to sunlight, causing itching, swelling and a stinging sensation) to allergic reactions – which lead to similar symptoms and are usually caused by certain metals used in red ink.

At least one in 10 people who get a tattoo experience skin reactions involving itching, pain, inflammation and swelling for at least three weeks after getting the tattoo, according to a study conducted last December by scientists at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, has been published. the journal Dermatology.

More recently, a study by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US found that a third of the 75 tattoo inks they tested contained potentially harmful bacteria that could lead to serious infections in some people.

More serious, albeit extremely rare, complications can include the life-threatening liver infections hepatitis B and hepatitis C, as well as HIV – almost always from contaminated needles. But now there’s another new concern about the possible link between tattoo ink and certain types of cancer.

In May, a study published in The Lancet reported that adults who had even one tattoo were 21 percent more likely to develop lymphoma – a form of blood cancer that affects more than 16,000 people in Britain every year.

The disease occurs when white blood cells called lymphocytes begin to grow uncontrollably.

Normally, in a healthy body, lymphocytes – which are part of the immune system – help fight infections. But they can cause cancer due to factors such as a weakened immune system or long-term exposure to chemicals such as pesticides or insecticides.

They then multiply uncontrollably, damaging vital organs: around 5,000 people die from lymphoma every year in Britain.

When scientists from Lund University in Sweden compared tattoo rates in 1,300 patients with various forms of lymphoma between 2007 and 2017 with healthy adults of the same age (20 to 60 years), those with body ink were more likely to develop lymphoma.

Perhaps surprisingly, the risk did not appear to increase with more tattoos; just one or two posed the same cancer risk as multiple tattoos. The researchers said: ‘Tattoo ink often contains carcinogens [cancer-causing] chemicals and we found it was linked to an increased risk of lymphoma – more research into this is urgently needed.”

In June 2023, the UK Health and Safety Executive announced that it was recommending the restriction of certain hazardous substances used in tattoo ink, which contains around 200 chemicals and additives. These include chemicals known to cause cancer, gene mutations, skin corrosion and serious eye damage.

It is not clear how exactly tattoo ink could trigger the cancer growth process in lymphomas. And other studies have found no such link with an increased risk of lymphoma.

But what research has shown is that the pigments used in ink can travel through the bloodstream and collect in the lymph nodes – the network of bean-shaped glands throughout the body that helps regulate the immune system’s response on foreign organisms.

Once there, they can clump together to form a semi-solid mass that, when viewed on an MRI scan, can look eerily similar to a cancerous tumor.

‘When the body metabolizes tattoo ink, it can sometimes build up in the lymph nodes in the neck, armpit and groin,’ says Dr Jonathan Kentley, consultant dermatologist at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London and spokesperson for the British Skin Foundation.

‘There have been cases where patients have had their lymph nodes surgically removed because they were thought to have cancer when they did not. Instead it was tattoo pigment.” The theory is that it solidifies and then calcifies into a lump.

When some cancers – such as breast cancer – spread through the body, they usually first move to nearby lymph nodes, in the case of breast cancer, in the armpit.

A 2022 report in the journal Cureus highlighted the case of the 36-year-old tattooed woman from Hobart, Tasmania, who underwent regular breast cancer screening because she had a genetic mutation that put her at very high risk. It was on one such scan that doctors noticed a small, hard mass in one of her breasts.

Dr. Jonathan Kentley, consultant dermatologist at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London

‘It’s not that the pigment necessarily causes harm, but rather that it can lead to confusion about whether it is cancer or not, sometimes forcing patients to undergo unnecessary procedures. [such as biopsies]’, says Doctor Kentley.

In addition, other studies have suggested that certain types of skin cancer are more likely to develop in tattooed areas.

In 2020, researchers at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire in the US studied 156 patients with tattoos who developed basal cell carcinoma – a form of skin cancer that affects around 75,000 people every year in Britain.

It usually occurs in areas most exposed to the sun, including the face. And while this type of skin cancer is rarely life-threatening, it can destroy surrounding facial tissue if not removed.

The study found that among patients with tattoos, the risk of cancer was 80 percent higher on inked skin than on clear skin, the journal Epidemiology reported, suggesting that tattoos increase the risk of cancerous growths.

Other research has also found that nearly 40 percent of skin cancers that form in tattoos develop in areas of red ink, possibly because exposure to the sun’s rays activates carcinogens found in this color of ink.

Meanwhile, using dark-colored ink can make it harder to detect malignant melanoma, the most dangerous form of skin cancer. Spotting dangerous moles at their earliest stages is critical to increasing your chances of survival.

Dr. Kentley warns against getting tattoos on parts of the body where moles appear. “Most good tattoo artists don’t tattoo over a pre-existing birthmark,” he says. “If we ever see cancerous moles in a tattoo, they are usually moles that have appeared after the tattoo was applied. But always research the tattoo artist first.’

Britain’s approximately 2,000 registered tattoo artists must be licensed by a local authority. ‘Make sure the one you choose is licensed and ask to see before and after photos from other clients first,’ advises Dr Kentley.

‘Tattoos can be removed, but most people underestimate the pain, the high costs and how long it takes. The lasers we use are expensive, the treatment can take five to twelve sessions and the bill can run into thousands of euros.’

The dangers of inking with your pet’s ashes

In recent years there has been a growing demand for so-called ‘memorial tattoos’, where relatives have the cremated ashes of their deceased family member or beloved pet mixed with the tattoo ink and used to decorate their body.

But is it safe? Although cremation (where temperatures exceed 1,000 degrees Celsius) destroys all bacteria, the risk of infection from injecting ashes into the skin remains, says dermatologist Dr Jonathan Kentley.

‘The ash must be incredibly sterile and stored properly so that no contaminants get into it. They also need to be ground finer than what comes out of the crematorium, otherwise the body can react to them as foreign material, causing a granuloma.”

This is a small, non-cancerous cluster of immune cells that forms a bump under the skin in response to infection or foreign bodies. Although easily treated with steroid creams, a granuloma can become painful and inflamed.

In 2014, a 48-year-old woman in the US died from a flesh-eating bug called streptococcal necrotizing myositis after becoming infected by a memorial tattoo on her back that contained her dog’s cremated ashes.