How Watching This 96-Year-Old Woman in the Dock Convinced Me That Those Who Aided the Nazis MUST Face Justice… No Matter How Old They Are

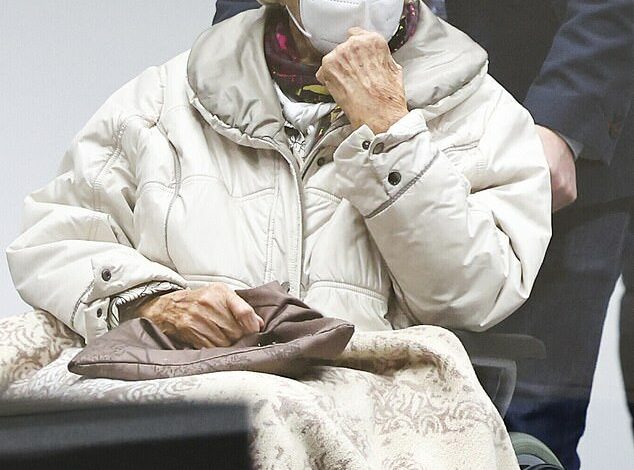

As she was wheeled into the courtroom in a wheelchair, the elderly woman’s face was hidden behind a printed silk scarf.

Sunglasses and a medical mask further protected her from press photographers who had been granted brief permission to take pictures. Irmgard Furchner was the first woman to stand trial in decades on charges related to Third Reich atrocities.

The trial began three years ago—bizarrely enough—in a juvenile court near Hamburg, Germany. She was just 18 when she began working as a secretary to the Kommandant of the Stutthof camp. I saw an electronic tag on her arm. It had been attached after she had fled her nursing home to avoid trial, an act that seemed to show that she understood the gravity of her plight.

Remember, this woman was accused of complicity in the deaths of 11,400 people at Stutthof, on Poland’s Baltic coast. This camp became the first Nazi camp outside Germany when it opened two days after the war broke out.

Despite her protestations of innocence, Furchner was convicted as an accomplice to mass murder and given a two-year suspended sentence. Her appeal against her conviction, now 99, was rejected last week by the German Federal Court.

Irmgard Furchner was the first woman to face trial in decades on charges related to atrocities committed in the Third Reich

When I first saw her in 2021, she looked sad and pitiful—like the 100-year-old man I saw in another German court two days later, dressed in a striped sweater and complaining of trouble sleeping when he was confronted with similar charges. The Lithuanian-born centenarian could not have looked less menacing. Yet this man, Josef Schutz, was found guilty of helping to slaughter 3,518 people at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin.

Not that he saw the inside of a cell. He was allowed to remain free while he appealed his five-year sentence, but died last year.

It felt strange to see the eerily familiar black-and-white images of Nazi guards parading through those horrific camps on the courtroom television screens – and then to look first at Furchner and then at Schutz as they claimed to be crucial cogs in the Nazi machine of mass murder.

The horrors of the past blended with today’s reality as Germany tracked down some of the last surviving alleged perpetrators of these crimes against humanity.

This series of cases followed the 2011 conviction of John Demjanjuk, a former guard at the Sobibor camp. Previously, German cases required evidence of involvement in a murder. But after that case, anyone who worked at such a site could be tried as an accomplice to the murders committed there.

This woman was accused of complicity in the deaths of 11,400 people in Stutthof, on Poland’s Baltic coast (Furchner pictured in 1944)

I was surprised by my reaction as I looked at these frightened old people. I had had ambivalent feelings about such trials beforehand, torn between the enormity of the Nazi crimes and the age of these defendants and the relatively small role they played.

But my attitude hardened as I looked at that miserable old woman and even older man. I became convinced that these trials were correct – even if they came decades too late and the accused were brought to trial partly because they lived longer than their contemporaries.

Oddly enough, it was the averageness of the suspects that heightened my desire for justice. The banality of evil was visible as Schutz listened through his headphones (due to hearing problems) and Furchner fiddled with her sunglasses.

At one point, Heike Trautmann, a high-ranking police officer, showed Schutz the court records of his service in the SS after he responded to the Führer’s call to join the Nazis.

Trautmann revealed that during Schutz’s 40 months as a guard at Sachsenhausen, 38,110 people were killed: “They were gassed, shot or died from malnutrition and poor hygiene.”

Heinrich Himmler (center) in Stutthof, the first Nazi camp outside Germany

She asked a court official to help her unroll the list on which the Sachsenhausen staff had detailed the daily killings of Allied prisoners, political enemies and “antisocials” such as Jews and Roma. Incredibly, the list was 45 feet long.

This was a shocking indication of the scale of these crimes and a reminder that even the most disturbing crimes are committed not by madmen and monsters, but by ordinary people, driven by typically human traits such as ambition, fear or a misplaced sense of duty.

To function effectively, the Nazi regime needed officials, guards, and secretaries. And as historian Rachel Century told me, if enough people had refused to cooperate, millions of lives could have been saved.

About 64,000 of the 110,000 prisoners held at Stutthof died, including some 28,000 Jews, political prisoners, homosexuals, and survivors of the Warsaw Uprising. Many were executed, but others died of disease, exhaustion, and starvation.

Asia Shindelman was 15 – three years younger than Furchner – when she and her family were taken to Stutthof in a cattle car. She told me she had seen her grandmother being led away to be murdered, prisoners being thrown onto electric fences, men being fed to dogs “like meat.”

“It’s not possible for someone to say that he didn’t know what was happening around him,” said Shindelman, who was among the 4 percent of Lithuanian Jews who survived the Holocaust. “We didn’t look like people — we looked like skeletons.”

It is easy to blame leaders for evil deeds, but the potential for depravity lies beneath the surface of all human societies. In my own lifetime I have seen it repeatedly: from the slaughter of two million Cambodians under the despotic Pol Pot and the Rwandan genocide to more recent events in the Middle East.

Or look at the horrific killings, rapes and tortures that Russian soldiers and their henchmen are carrying out in Ukraine. Is it any wonder that Ukrainians are enraged when outsiders blame Putin for the nightmare that is engulfing their country?

During my reporting around the world, I have met many victims of abuse and torture and have often wondered how anyone could commit such atrocities.

A few weeks before I attended those trials, I interviewed a Chinese police officer who told me how he had helped beat and abuse Uighurs in the dictatorship that oppressed Muslim minorities. He told me about flogging people until they went blind and using electric batons on genitals.

This man was a whistleblower who fled China out of disgust at his own role in these sordid events. He was remorseful. Yet he showed how a warped sense of duty and fear of punishment led an ordinary man to help torture innocent people.

That’s why those trials are so important and why I changed my mind when I looked at those two old people.

They remind us how ordinary men and women complicit in and carry out the most horrific crimes.

And for the sake of humanity, we must send an unwavering message to all who participate in such atrocities: they will never be safe from justice.