I was dragged into a bush and had my genitals butchered during the FGM ritual when I was six

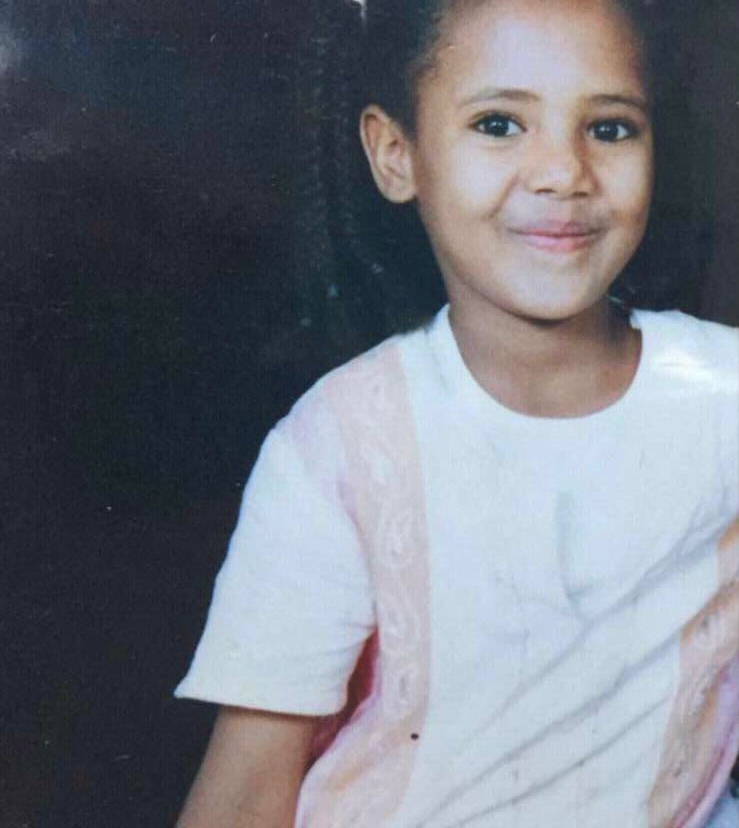

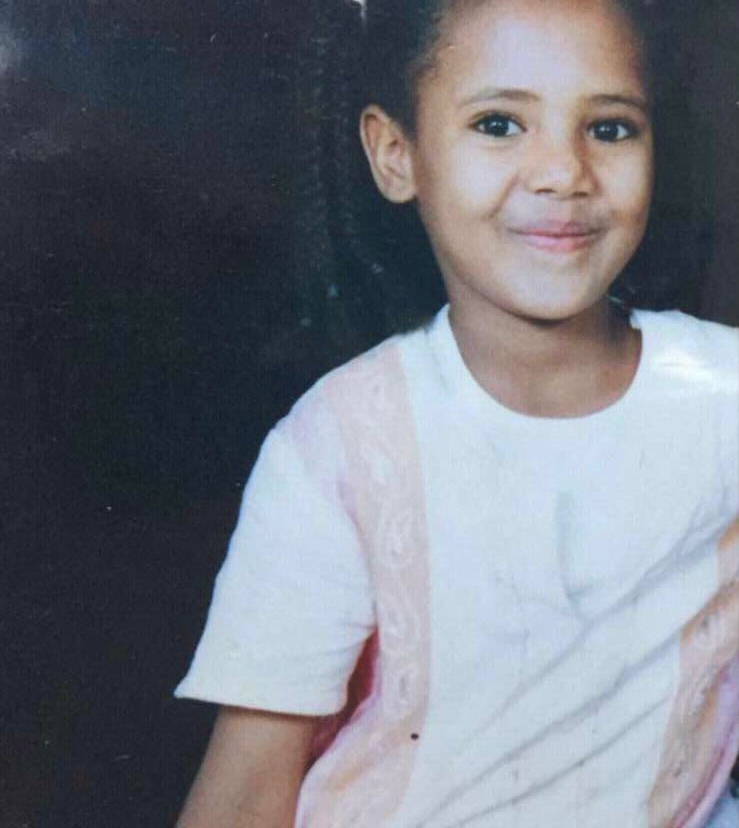

YOUNG and innocent, Amana Abby thought she was the luckiest girl in the world when friends and family started giving her money and sweets at the age of six.

She had no idea she was about to be dragged into a bush, held down and forced to lie with her legs open as part of a horrific ordeal that would change her life forever.

“I don’t remember anything from that moment until the moment I woke up in bed and my legs were tied with ropes,” she recalls.

The trauma was so severe that Amani, 24, a student from Sheffield, South Yorks, blacked out. She didn’t even realize she was a victim of female genital mutilation (FGM) until she was a teenager.

The gruesome procedure, which involves removing all or part of the external female anatomy for non-medical reasons, has been illegal in Britain since 1985. It is classified as child abuse and can cause long-term problems with sex, childbirth and mental health. .

However, in Sudan, where Amani grew up, the practice remains common for “religious purposes,” despite it eventually being made illegal there in 2020. According to the UN, 87% of Sudanese women between the ages of 14 and 49 have undergone some form of FGM. .

READ MORE REAL LIFE STORIES

Amani grew up with her parents, brother and sister in a small village in Sudan, before moving to Britain at the age of nine. Now, 16 years after her ordeal, she tells her story exclusively to Fabulous as she campaigns to stop this happening to other young girls.

“I wasn’t actually told anything in advance,” she says. “I was just a kid, and can you imagine telling a kid what would happen to him or her?” she says.

The children were often left to fend for themselves and never received much attention from the adults, who were too busy trying to make ends meet – but, as Amani explains, this day was different.

“That day they gave me a lot of attention. I remember the older men and older women I had never spoken to before putting money in my shirt and giving me sweets.”

Just a child

Then a large group of people led her to a nearby field where they planted crops to eat, before leaving her with her grandmother, aunt, mother and a few other women.

“I remember them holding me tight, at one point grabbing me and telling me to lie down,” she explains. “And then suddenly they held me very tightly. After that I can’t remember anything.”

Amani was given no anesthesia or painkillers, and after she came to, she remembers her mother picking her up and putting her on a bright pink potty.

“My legs were still tied and she kept telling me to pee.

“I just remember screaming and crying and saying, ‘I can’t pee, I can’t pee.’”

Amani later learned from her aunt that she had contracted a serious infection – a common complication of FGM, resulting from the use of unsterilized tools – and her family prepared for the worst.

Despite being so weak she couldn’t even drink, Amani said they refused to take her to the doctor because it was too far away.

What’s the point in mutilating a child’s organs if they are healthy and perfectly fine?

Amani Abby

“Who would put a child through something so horrific?” she says. “What is the rationale for mutilating a child’s organs if they are healthy?”

It wasn’t until high school in Britain, when Amani took sex education classes learning about the female anatomy, that she realized what had been done to her.

“I remember seeing pictures of the vagina and the different parts of it, the vulva, the clitoris. I was really fascinated.

“I thought, ‘This isn’t like my vagina.’ Mine was all sealed and closed. I asked the teacher: ‘Do all vaginas look like this?’

“The teacher said, ‘Yes, they do.’”

Amani was so shocked by the revelation that she took the textbook home to show her mother, asking if hers were different because they were from a different country. She remembers her mother immediately ending the conversation, saying it was “embarrassing” to watch such images.

It is this belief that women are not meant to have a sexual identity.

Amani Abby

Afterwards, her mother went to the school and warned them not to teach her daughter about sex education, so Amani decided to do her own research.

She started Googling and came across the term ‘FGM’. When she put two and two together, she realized that this had happened to her all those years ago, and confronted her mother.

“When I asked about it, they said, ‘Oh, we did it because it’s religious. It guarantees your purity and your virginity,” she explains, adding, “Which is not true. Religion does not promote violence against women. It certainly does not promote violence against children.

“It’s the belief that women are not meant to have a sexual identity.”

Because talking about sex was a taboo in her household, Amani never told anyone about FGM until she left home at the age of 16.

After an argument with her father, she lived with foster parents for a month before living independently.

By then, her mother had given birth to two more girls, and Amani realized that they were reaching the age she was when she was circumcised.

Despite having no contact with her family, she vowed not to let this happen to her sisters and called the police to initiate an FGM protection. This meant that they could not travel to Sudan without checks to prevent her sisters from experiencing this too.

WHAT IS FGM AND HOW CAN IT BE TREATED?

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is an illegal procedure in which the female genitalia are deliberately cut, injured and altered.

It is also called ‘female circumcision’ or ‘cutting’ and it is child abuse.

The NHS states that there is no medical reason to do this.

There are four types of FGM

Type 1: Removing part or all of the clitoris.

Type 2: The removal of part or all of the clitoris and the inner labia (lips surrounding the vagina), with or without removal of the labia majora (larger outer lips).

Type 3: Narrowing of the vaginal opening by creating a seal formed by cutting and repositioning the labia.

Type 4: Piercing, piercing, cutting, scraping, or burning the area.

Source: NHS

What are the side effects?

- Constant pain

- Pain and/or difficulty with sex

- Repeated infections, which can lead to infertility

- Bleeding, cysts and abscesses

- Problems with urination or incontinence

- Depression, flashbacks and self-harm

- Problems during childbirth, which can be life-threatening for mother and baby

- Some girls die from blood loss or infection as a direct result of the procedure

How can it be treated?

An operation called deinfibulation may be performed to open the vagina.

It is also called a ‘reversal’, but the NHS says this is misleading because the procedure does not replace the tissue removed or undo the damage caused by FGM.

Surgery may be recommended for women who cannot have sex or have difficulty urinating, or for pregnant women who are at risk of problems during delivery due to FGM.

Deinfibulation involves making an incision to open the scar tissue above the entrance to the vagina and is usually performed under local anesthesia.

New beginning

Amani’s determination to ensure FGM is banned around the world has only grown now that she has become a mother herself.

Most FGM procedures involve suturing up to the opening of the vagina – meaning women can have sex, even though it is usually extremely painful.

She became pregnant with daughter Maya in 2021 with her partner Ali and decided to opt for a caesarean section to ensure that there would be no complications during delivery due to FGM.

“The whole process was so peaceful. The recovery was very painful, but I was sure she was fine and so was I,” she says.

“That was the best feeling ever. I was so scared and had panic attacks for nine months thinking she was going to die, I’m going to die.

“I was so happy, I had started a family. I don’t have my old family anymore, but I have created my own.”

After recovery, Amani inquired about reversing FGM – a procedure not often talked about, but available on the NHS at Blossom Clinics.

The clinics providing a safe space to talk about FGM, therapy sessions and access to procedures to reverse the physical effects.

“My biggest concerns were painful intercourse, sometimes impossible intercourse. Also urinary tract infections because it is not easy to clean. The urine would have to penetrate beneath the scar tissue, which is sometimes quite painful,” says Amani, who is now studying medicine at university and hopes to open a non-profit charity in the future.

“Then there is the psychological pain and the feeling that your body is failing you in that area.”

Amani says she went through with the surgery for her daughter, adding that the physical pain of constantly living with FGM would traumatize her – something she wanted to escape when she became a mother.

It also prompted Amani to discuss FGM and her story on social media @amanibdh8 to educate people about the dangers and campaign against it happening to other girls.

A year after giving birth, Amani had the recovery procedure performed and couldn’t be happier with the results for her and her family.

“I was able to take back my power and change things for the better for myself.”