It’s not just Gaza: Student protesters see links to global struggle

Talk to student protesters across the country and their outrage is clear: they are galvanized by the scale of death and destruction in Gaza and will risk arrest to fight for the Palestinian cause.

For most of them, the war is taking place in a country they have never set foot in, where the deaths (34,000 so far, according to local health authorities) are known only through what they have read or seen online.

But for many, the problems are closer to home, and at the same time much bigger and broader. In their eyes, the conflict in Gaza is a struggle for justice, linked to problems that seem far away. They say they are motivated by policing, mistreatment of indigenous people, discrimination against Black Americans and the impact of global warming.

In interviews with dozens of students across the country over the past week, they strikingly described the broad prism through which they view the Gaza conflict, which helps explain their urgency – and revulsion.

Ife Jones, a freshman at Emory University in Atlanta, drew connections between her current activism and the civil rights movement of the 1960s, in which her family participated.

“The only thing missing was the dogs and the water,” Ms. Jones said of the current backlash against protesters.

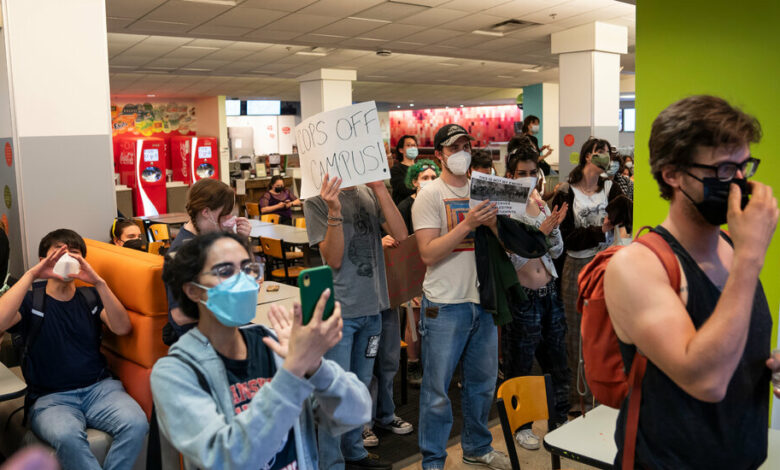

Many protesters have rejected pleas from university administrators, chained themselves to benches and taken over buildings. Now, protesters are being cracked down on, with hundreds of arrests in the past 24 hours at many schools, including Columbia University.

With pro-Israel students stepping up their counter-protests on multiple campuses, the climate could become even more tense in the coming days.

In interviews, the language used by many protesters was also distinctive. Students liberally peppered their statements with academic terms like intersectionality, colonialism, and imperialism, all to make their case that the plight of Palestinians is the result of global power structures that thrive on prejudice and oppression.

“As environmentalists, we pride ourselves on seeing the world through intersectional lenses,” said Katie Rueff, a freshman at Cornell University. “Climate justice is everyone’s business. It affects every dimension of identity because it’s rooted in the same struggles of imperialism, capitalism and all that. I think that is certainly true of this conflict, of the genocide in Palestine.”

Jawuanna McAllister, a 27-year-old PhD candidate in cell and molecular biology at Cornell, pointed out the name of the student group she belongs to: the Coalition for Mutual Liberation.

““It’s in our name: mutual liberation,” Ms. McAllister said. “That means we are an anti-racist, anti-imperialist, anti-colonial organization. We believe that none of us can be free and have the respect and dignity that we deserve unless we are all free.”

Nearly all protest groups want an immediate ceasefire and some kind of divestment from companies with interests in Israel or the military. But because everything is connected, some protesters have other items on their agenda.

At the University of California, Los Angeles, students like Nicole Crawford are demanding that the school sever its relationship with the Los Angeles Police Department, along with calls for greater transparency about the school’s investments. Ms. Crawford, 20, said she connects the suffering of Gazans to the plight of other oppressed people around the world.

“Being part of an oppressed group, especially people who experience direct state violence, such as being part of the Pan-African diaspora in the United States, which is built on the enslavement, dehumanization and degradation of African peoples, politicizes it. you,” said Mrs. Crawford.

At Emory University, protesters occupying the campus have chanted “Free Palestine” along with “Stop Cop City,” referring to a large police and fire training complex being built on the outskirts of Atlanta.

Ari Quan, a 19-year-old Emory freshman from Columbia, S.C., who uses the pronouns they and them, acknowledged that he had not followed the Gaza conflict particularly closely, but said there was significant overlap between the movement for more justice in policing and pro-Palestinian sentiment. They were moved to join the campus demonstrations after witnessing their friend being pushed to the ground by police.

“I would have felt bad if I wasn’t involved,” they said. “I find it hard to imagine the police becoming more and more militarized.”

The student movement in support of Palestinians has been built over decades by connecting with other issues. Students for Justice in Palestine, a loosely knit confederation that formed in the early 1990s at the University of California, Berkeley, deliberately invited other activists — environmentalists, opponents of U.S. intervention in Latin America, critics of the Gulf War — and broadened the group’s base.

Today, the group’s national steering committee claims more than 200 autonomous chapters, most of them in the United States. And they often work together with other student groups.

Coalition building is a source of strength and pride, giving protesters the feeling that much of the world is behind them.

But scholars say this current movement, which has angered many pro-Israel students and alumni, is starkly different from the movements against apartheid in South Africa or the Vietnam War.

In the 1960s, during the anti-Vietnam War protests, no voter group felt attacked as an ethnicity, says Timothy Naftali, who teaches public policy at Columbia, though he acknowledged that student soldiers or ROTC soldiers may have been targeted.

“I imagine these demonstrations now create a sense of insecurity in a much greater way than the anti-war demonstrations during Vietnam,” Mr. Naftali said.

Much of the divide today centers around Hamas and anti-Semitism.

In interviews, many students refused to answer questions about Hamas, the militant group that led the October 7 attacks in Israel that killed 1,200 people. Many simply said the attacks were horrific.

But Lila Steinbach, a senior at Washington University in St. Louis, acknowledged that the attacks stirred complicated emotions. She knows people who were killed and held hostage in the attacks. Like many of the protesters, she was raised Jewish.

“What happened on October 7 was a test of my politics, as someone committed to liberalization and decolonization,” she said, adding: “It is difficult not to condemn all the violence perpetrated by Hamas.”

Yet, she added, “I also know that the violence of the Israelis and the violence of American imperialism and the conditions created by those actors are responsible for breeding terrorism. If you grow up in an open-air prison and you become an orphan and you are told that the Israelis are to blame, why wouldn’t you believe them?”

Anti-Semitism is a real concern, as almost all student protesters indicated.

But they said they just didn’t see it around them — not in their encampments, not among the other protesters, not in their chants, such as “from the river to the sea.” (According to them, “from the river to the sea” is not a call to eradicate the state of Israel, but a call for peace and equality.)

On Sunday, a few dozen protesters hung around the University of Pittsburgh camp. Alexandra Weiner, 25, a faculty member in the university’s math department, said she grew up at the Tree of Life Synagogue, where a white nationalist shot 11 churchgoers in 2018.

While some counter-protesters called the camp anti-Semitic, she said, “I have not experienced or heard any sentiment of anti-Semitism.”

Later that day, hundreds of protesters marched on campus calling for a ceasefire. After a brief confrontation with police, two were arrested. By Tuesday, the camp was gone.

Alan Blinder, Neelam Bohra, Patrick Cooley, Jill Cowan, Jenna Visser, Sean Keenan And Cole Louison contributed report.