Lockdowns cause teenagers’ brains to age prematurely by up to four years, study finds

A US study shows that the brains of teenage girls may have aged up to four years earlier during the Covid pandemic.

Adolescent boys were also not immune to this phenomenon. Their brains also showed signs of excessive wear and tear, although this occurred after only one and a half years.

Experts say the difference is because social restrictions during the lockdown have had a disproportionate impact on teenage girls.

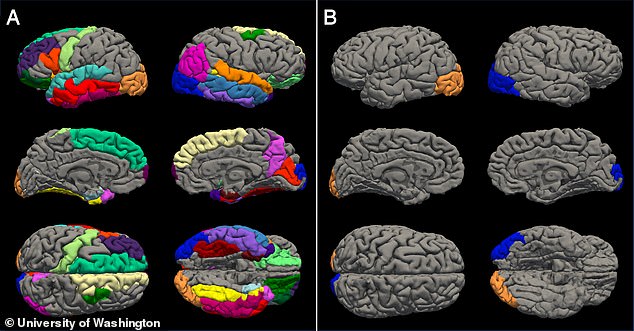

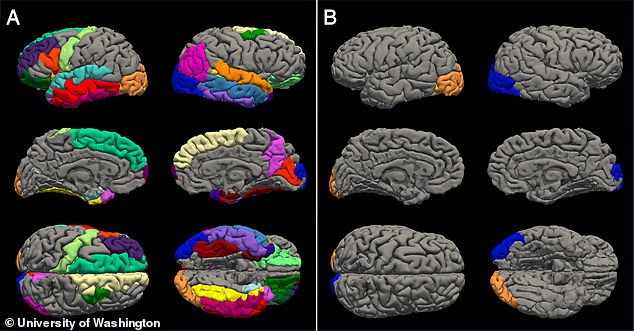

Researchers at the University of Washington looked at 160 MRI scans taken in 2018 from a group of 9- to 17-year-olds. They then compared them to 130 scans taken after the pandemic, in 2021-2022.

They found that a process called cortical thinning — in which the organ effectively rewires itself between childhood and adolescence — was much more advanced than it should be in teens who participated in the pandemic.

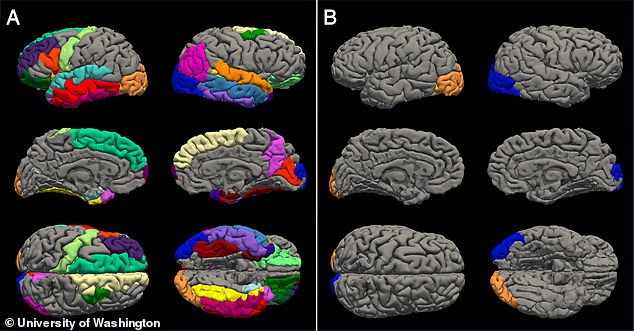

The brains of teenage girls (left) may have aged up to four years prematurely during the Covid pandemic, a US study suggests. Adolescent boys were not immune either, with their brains also showing signs of unnecessary wear and tear, albeit by only a year and a half (right)

Although cortical thinning occurs naturally, some studies have linked accelerated thinning to exposure to fear or stress and a greater risk of developing these conditions in the future.

It is not yet clear whether the observed dilution is permanent or whether it will have negative consequences for teens’ long-term health or educational aspirations.

The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesalso found differences in which parts of the brain aged in boys and girls.

For example, in both sexes there was an accelerated aging of the organ involved in processing visual information. In girls, however, there was also an early thinning of the areas associated with emotions, interpreting faces and understanding language.

These are all aspects that are crucial for effective communication.

According to the study’s author, Professor Patricia Kuhl, an expert in learning and brain sciences in Washington, the researchers were shocked by the magnitude of the difference between boys and girls.

She told the New York Times ‘a girl who came in at age 11 and returned to the lab at age 14 now has a brain that resembles that of an 18-year-old;.

Professor Khul also told the Guardian that she believes part of the difference is due to the fact that teenage girls are more dependent on social groups than their male counterparts.

‘Girls chat endlessly and share their emotions. They are much more dependent on the social scene for their well-being and for their healthy neural, physical and emotional development.’

She added that the findings are “a reminder of the vulnerability of teenagers” and suggested that parents take the time to talk to their children about their experiences of the Covid pandemic.

“It’s important that they invite their teens in for a cup of coffee, a cup of tea, a walk, to open the door for a conversation. Whatever it takes to get them to open up.”

The research is the latest to suggest that the Covid pandemic and lockdown measures that kept family and friends apart for months have had a negative impact on young people’s mental health.

However, some experts warn against overinterpreting the study’s findings.

One of them was Dr. Bradley S. Peterson, a child psychiatrist and brain researcher at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study.

He noted a number of limitations. One is that the authors were keen to link the changes to the social isolation caused by the lockdowns, but other possibilities exist, such as increased screen time and social media use and reduced physical activity.

Dr. Peterson also said that the observed decrease in hair growth may not be a bad thing and that it “could reflect the brain’s natural adaptive response that allows for greater emotional, cognitive and social resilience.”