Melodies of popular songs have become simpler over time

“Well, we’re all in the mood for a melody,” Billy Joel sings in “Piano Man,” his iconic 1973 barroom ballad. That may have been true when Mr. Joel was wearing the clothes of a younger man, but a new study by computational musicologists at Queen Mary, University of London, has found that vocal melodies in popular music have become much less complex over time.

The study, published on Thursday’s study in the journal Scientific Reports used mathematical models and algorithms to identify three “melodic revolutions” — in 1975, 1996 and 2000 — that progressively simplified the two key components of melody: rhythm, or the pattern of sounds and silences in a piece of music, and pitch, the measure of how high or low the notes are.

The study looked at the top five Billboard songs from 1950 to 2023. Both rhythm and pitch became less complex over that time period, the study found. “Conservatively, they both declined by 30 percent,” said Madeline Hamilton, a graduate student at Queen Mary University of London who led the research.

Captain & Tennille’s 1975 hit “Love Will Keep Us Together” contains many unexpected notes and rhythmic complexity.

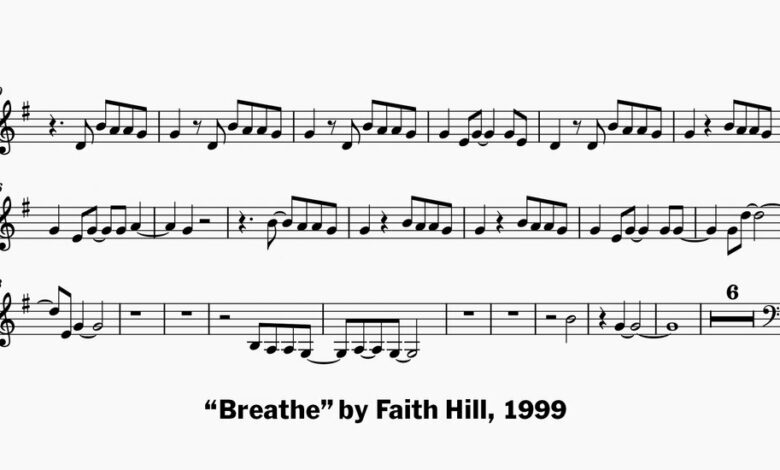

Faith Hill’s “Breathe,” the most popular song of 2000, has no key signatures, lots of repetition, and simple rhythms.

The simplification of melody is not a new concern for some musicologists. “The place of melody as one of the basic building blocks of music is being substantially reduced,” said composer Yuval Shrem wrote in a 2014 article for Keyboard magazinecited in the study. But the new research adds rigorous quantitative evidence of that trend.

Ms Hamilton and her advisor, Marcus Pearce, the leader of the music cognition lab at Queen Mary, found that other aspects of popular music, such as the number of notes played per second, actually increased over time, suggesting that the loss of melodic complexity came down to some kind of trade-off. The shift may have been due to advances in technology.

“Today, anyone with a laptop and an Internet connection can create any sound they can imagine, thanks to the accessibility of digital music production software and libraries of millions of samples and loops,” the researchers wrote.

They warned against making value judgments about melodic loss, as the trend could easily fall prey to culture wars between classical and contemporary music, they said in an interview.

“It’s not that the music becomes less complex,” Ms. Hamilton said. “The melody becomes less complex, but maybe the chords become more complex, or maybe the production.”

Melodies are generally pleasant to listen to, which is why we find ourselves singing along to the opening bars of Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 5” or Lady Gaga’s 2008 hit “Poker Face.”

“Melody often has the clearest potential to be the heart and soul of a piece of music,” said Oscar Osicki, a composer who Within the scorea YouTube channel about music. “It’s what draws us in, evokes our emotions and makes our soul dance to its contours.”

When Ms. Hamilton began researching melodic aesthetics in 2019 in preparation for a dissertation, she encountered a shortcoming that would dominate her career for years to come. “I noticed that all the datasets that were available were classical and folk music, which I found kind of odd,” she said. “That’s not really representative of what people listen to every day.”

Mrs. Hamilton decided to create her own dataset using the Billboard Melodic Music Datasetwhich contains 1,131 files featuring melodies from the top five most popular Billboard songs from each year from 1950 to 2022. (Ms. Hamilton uploaded last year’s hits, led by Morgan Wallen’s “Last Night,” on her own.)

She listened to all 366 songs in the database and transcribed the vocal melodies – about three per song – into MuseScore, an online music notation program.

By then, London was in lockdown because of the coronavirus, and Ms. Hamilton was spending much of her time alone in a dorm room, listening to tunes for up to 10 hours a day. Still scarred by the experience, she can’t listen to much popular music anymore, though no song haunts her more than the UB40 version of Elvis Presley’s “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” which reached No. 3 on the Billboard year-end chart in 1993.

Ms. Hamilton measured eight melodic metrics, four related to rhythm and four related to pitch, for each melody of every Billboard song in the data set. These included, for example, the number of notes per measure and the average melodic interval between successive pitches. Roger Deana molecular biologist, musicologist and composer at Western Sydney University in Australia, provided crucial assistance, as well as what Ms Hamilton called “sanity checks”.

Ms. Hamilton also used a statistical model developed by Dr. Pearce to measure how predictable each melody was in terms of both rhythm and pitch. “The model ‘guesses’ what note will occur next in the melody based on the previous notes in the melody,” Ms. Hamilton said. “It then returns a value that represents how ‘surprised’ the model was on average throughout the melody.”

Ms. Hamilton then used algorithms that linguists have used to shifts in language use to reveal the timing of key moments in pop’s evolution. She found that melodic complexity declined sharply in 1975, around the time that disco and stadium rock were gaining popularity. There was a less dramatic decline in 1996, which coincided with the growing appeal of hip-hop and electronic music, along with the popularity of MTV. Another major melodic cliff appeared in 2000, most likely a product of the same forces at work throughout the 1990s.

Digital culture, including social media, may also have habituated people more broadly to smaller units of information. “As our brains become accustomed to reading and writing broken sentences to fit within various digital character limits, our brains ultimately no longer expect, require, or desire the fully formed sentence, musical or otherwise,” Mr. Shrem wrote in his 2014 article for Keyboard.

Pharrell Williams’ “Happy,” the number one song of 2014, had high production value but low melodic complexity.

But others say the shift away from melodic variety makes sense because the human mind can only handle so much complexity. As music has become more innovative in some ways thanks to the proliferation of digital tools and cultural shifts, it has had to sacrifice creative nuance elsewhere, he said. Patrick Wildemusicologist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand.

“We can’t enjoy things that are too complex to understand, remember or reproduce,” he said. “There are sort of limitations to that.” Dr. Savage added that one limitation of the new study was that it couldn’t fully account for the specific complexities of rap music. “Western notation wasn’t designed to capture the speech-like microtonalities of rap, which are in some ways arguably more complex than typical sung melodies,” he said.

Ms. Hamilton agreed that melodic complexity is not an indicator of musical quality. “Simplicity,” she said, “has its own beauty.”