My Unlikely Path from Prison to Journalism

Times Insider explains who we are and what we do, and offers a behind-the-scenes look at how our journalism works.

I never expected to become a real reporter. While the other students in my first journalism class could go out into the community to interview sources, my options were limited. As a prisoner, the only people I could interview were other prisoners and the guards.

It was 2010, and I was a 28-year-old alcoholic with a crack addiction serving a year in a county jail in Wisconsin. I had been convicted of burglary after breaking into a bar and walking out with a bottle of booze. It was a felony, and it came at just the right time—the height of car wrecks, lost jobs, and DUI arrests. When the judge sentenced me, he said I was an example of “a waste of a human life.” He was right.

During those first months behind bars, there was no sun, no night sky. I measured the time by the opening and closing of the steel cell doors. But halfway through my sentence, as is usual in many cases, the judge gave me the option of working during the day or taking classes at a nearby university.

I took a cleaning job in the community, excited to be out of my cell. One morning, as I vacuumed, I picked up a Rolling Stone magazine from a coffee table. Out came a flyer for a journalism contest at the university; winning entries would appear in the magazine. Only students were allowed to enter.

I knew nothing about journalism, but I had a strange feeling—an intuition—that I had finally found something I didn’t even know I needed. That day, I enrolled in the university closest to the prison.

So I found myself weeks later interviewing my correctional officer for a story in the student newspaper. We had never spoken so intently and precisely. This was someone who, at no other time, had absolute authority over me. Yet in that moment, as I interviewed him, I felt a subtle and tangible shift in power.

I felt him calculating what he wanted to say, leaving out words that might get him into trouble. I felt empowered to pursue those pregnant pauses, to seek out the truth and bring order to the world around me. The experience was liberating. It showed that even a prisoner’s voice could resonate when facts and thorough research supported what he or she had to say.

After my release, I stayed in school and eventually earned a master’s degree in journalism. And I kept writing. Story by story, and with the help of patient editors, I learned how to report and write better and faster. I got sober. Eventually, I got an internship as a reporter, and then a full-time job.

In the years since, I’ve been a reporter in California and returned home to take a job as a reporter at Wisconsin watch — the place where I was offered my first internship.

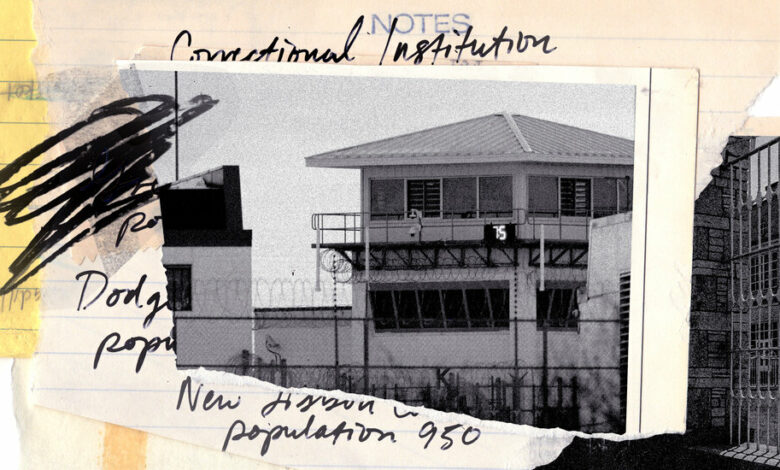

And then, last June, 13 years after I wrote my first article from a Wisconsin prison, I began covering the state’s prison system as a New York Times Local Investigations fellow. The fellowship program is designed to amplify the power and reach of local journalism.

By then I had a growing pile of letters from men in Waupun Correctional Institution, who had been locked in their cells for months on end without regular access to showers, fresh air, family visits and timely medical care. In August, under the leadership of a team of editors that included Dean Baquet, a former managing editor of The Times, I broke the story that the state was closing prisons because of staff shortages.

In February, we revealed that the state had known for years that it was losing guards faster than it could replace them. In June, I reported on the extraordinary arrests of nine prison workers, including a former guard, in connection with a series of inmate deaths.

In our last article we revealed another fact: Nearly a third of the 60 doctors employed by the prison system over the past decade have been disciplined by a state medical board for malpractice or an ethics violation.

My past has put me in a unique position. As a reporter, I purposefully distance myself from my investigations in order to follow the truth, wherever it leads. I value independence. But like everyone else, I have been shaped by my experiences. I know the smell of prisons and the ever-present hunger that prisoners feel. I know what it’s like to go months without fresh air. I’ve also seen the unexpected acts of kindness that happen behind bars.

My experiences shape who I talk to — and who talks to me — and how I approach my reporting. For better or worse, I am a member of this community forever. And that is the spirit of local journalism.