Our Australian dream… in the welfare ghetto: Private owners who bought homes in Australia’s poorest suburbs reveal the reality of their new lives – and what they think of their notorious neighbours

It’s just after midday on a Tuesday.

While most people are at work, unemployed Rayleen is speaking to me outside her dilapidated housing estate in Claymore, where she has spent most of her life.

She isn’t thrilled about being moved from her government-funded townhouse situated in one of Australia’s most impoverished areas, even if she has been promised another home in a neighbouring suburb.

Despite the heavy crime and poor living conditions Rayleen, 56, believes Claymore, on Sydney’s western fringe, ‘isn’t as bad as it looks’.

Located 54km southwest of the CBD, it is predominantly made up of social housing and known for its high unemployment and antisocial behaviour. Back in 2012, the suburb became notorious as the subject of an ABC Four Corners documentary, titled ‘Growing Up Poor’, which put a spotlight on Australia’s poverty problem.

But change is on the horizon: Claymore is in the process of being transformed thanks to a major social housing redevelopment that will see government housing and private owners living side-by-side.

As part of that process, some of Claymore’s long-term residents are being turfed out and their homes – many of them already virtually unlivable – demolished.

‘We’re out of here at the end of the month,’ Rayleen tells me.

Rayleen, 56, has lived in Claymore for most of her life. ‘We’re out of here at the end of the month,’ she tells me. The suburb is undergoing a major social housing redevelopment that will see government housing and private owners living side-by-side

Many of the homes in Claymore were left abandoned after residents were rehoused and are awaiting demolition. These empty homes are routinely ransacked and vandalised

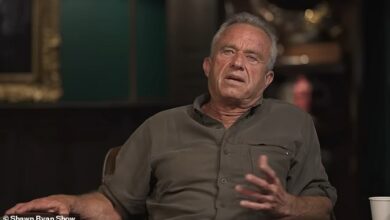

Social housing tenants are being scattered throughout Claymore, and their homes will be indistinguishable from the privately owned ones. Private owner Saifur Rahman (above) says he expected trouble when he moved in last year with his family – but was pleasantly surprised

Jesminder (left) has been living in Claymore for five years. She has heard about crimes in the area but says she and her family have ‘always felt safe’. Morna (right) finds the area ‘really quiet’ and says ‘we haven’t had issues with the original Claymore residents’

‘Leumeah and Minto are the two options being offered for us to relocate to, but I’m happy where I am. Claymore isn’t as bad as it looks.’

The mum-of-three is on JobSeeker payments after being made redundant from her factory job last year. Her husband, with whom she is no longer romantically involved but still lives with, works as a concreter.

‘We’re looking at going private because the houses they’ve offered us back on to a creek and we have grandchildren, so that’s not a safe environment for when they come and stay,’ she says.

Claymore became the ground zero of Australia’s poverty problem in 2012 when the Burns family opened the doors of their rundown townhouse to an ABC Four Corners crew. (Jessica Burns is seen with her parents Brett and Caroline at their former home in Claymore)

When I visited Claymore, the Burnses had already left; they were one of the families who had been rehoused to nearby Minto. Perhaps unsurprisingly, shortly after leaving Claymore, the Burnses’ three-bedroom house was swiftly vandalised and trashed by local thugs

The Claymore housing estate was built by the NSW Government in the 1970s and is home to more than 3,000 of the state’s poorest families.

Forty years on it remains a depressing sight, with burnt-out and abandoned homes in a rubbish-strewn cul-de-sac-style neighbourhood.

But Claymore, along with nearby Bonnyrigg Heights and Airds, is undergoing a radical redevelopment – perhaps one of the most ambitious social projects in years.

The old townhouses are being demolished, one by one. In their place a mix of new public and privately owned homes will be constructed.

The process has already started: a new housing estate, Hillcroft, is a modern, socially mixed community set on 125 hectares in Claymore.

Saifur has already seen first-hand the change that is happening in Claymore because he used to to live in Minto, 11 minutes’ drive away

Social housing tenants are being scattered throughout Claymore, and their homes will, in theory, be indistinguishable from the privately owned ones.

One private owner is Saifur Rahman, originally from Bangladesh, who moved to the new development in October last year with his wife and young family.

He says he expected trouble – but was pleasantly surprised.

‘We were expecting some vandalism, some break-ins, because that’s what I heard from other people,’ he explains.

‘We’re still prepared for it but we have [security] cameras everywhere.’

Home CCTV and doorbell cameras are a common sight on my visit to Claymore – in fact, they are the easiest way to tell which homes are privately owned.

‘We’re both working from home, me and my wife, and it’s been a fantastic experience moving here,’ adds Saifur.

‘It’s multicultural, lots of young families and no trouble at all.’

Saifur has already seen first-hand what is happening in Claymore because he used to to live in Minto, just 11 minutes’ drive away.

‘The government did the same thing there – demolished everything and people were moved out of the area and public houses became scattered among private homes, which is what they’re doing here,’ he says.

Claymore resident Jesminder has been living in the area for five years. She has heard about local crime but says she and her family have ‘always felt safe’.

‘We are all good but some of our neighbours have complained of break-ins,’ she says.

‘Someone was robbed at gunpoint and recently there was a shooting nearby. We hear about crimes but we have never had any issues ourselves.’

Another local, Morna, says he found the area to be ‘really quiet’ and hasn’t had any problems with his neighbours in public housing.

‘As far as I know of there has been no crime on the street and we haven’t had any issues with the original Claymore residents,’ he tells me.

Matriarch Caroline Burns (pictured) says her family is ‘doing well’, but it’s clear the spectre of poverty still looms large over their lives

Claymore became synonymous with Australia’s poverty problem in 2012 when the Burns family opened the doors of their rundown townhouse to an ABC Four Corners documentary crew.

Married couple Brett and Caroline Burns and their children, Jessica, Hayden and Hayley, were featured in the memorable episode ‘Growing Up Poor’, which followed their chaotic lives on welfare in a suburb where the majority of residents lived in state housing.

The episode ended with their prospects of a brighter future looking slim.

When I visit Claymore, they have already left. They are one of the families to be rehoused to nearby Minto after years on the waiting list.

At the time of filming, the family had been living in their ramshackle home for 13 years. They would eventually spend 24 years there.

The Burnes’ new home in Minto, 11 minutes’ drive from Claymore, is pictured. Public housing like this is surrounded privately owned ‘McMansions’ on Sydney’s western fringe

Pictured: A large private home with a ‘for sale’ sign out the front in Minto

The privately owned homes in Minto, where the Burnses have been rehoused, are usually differentiated from the public housing because of their modern ‘Australian McMansion’ style

Home CCTV and doorbell cameras are a common sight during my visit to Claymore – in fact, they are the easiest way to tell which homes are privately owned

Perhaps unsurprisingly, shortly after leaving Claymore, the Burnses’ three-bedroom house was swiftly vandalised and trashed by local thugs.

Catching up with the family in Minto, it’s clear the move hasn’t solved their problems. Even with a new home, they continue to be affected by the cycle of grinding poverty.

Hayden, whose struggles with bullying were particularly poignant in ‘Growing Up Poor’, now spends his days rummaging through bins around the neighbourhood in search of empty bottles and cans he then exchanges for a 10c refund.

Despite it all, Caroline is keen to put a positive spin on the situation.

‘We’re in a much better way now. It’s a beautiful area [in Minto] and we have a lovely house,’ Caroline proudly tells me.

‘We’ve been blessed.’