Rich Gulf states have enormous ambitions. Will extreme heat stop them?

The rich oil states of the Persian Gulf have big plans for the future. They want to attract more tourists and investors, organize major sporting events, build new cities and diversify their economies and make them less dependent on oil.

But they face a looming threat from which they cannot easily escape: the extreme and sometimes deadly heat that burns their countries every summer, and which climate change is expected to worsen in the coming decades.

Scorching temperatures are driving up energy demand, wearing down infrastructure, endangering workers and making even simple outdoor activities not just unpleasant but potentially dangerous. All of this will put a significant strain on the Gulf states’ vast ambitions in the long term, experts say.

“We keep thinking that we want to get bigger and bigger, but we don’t think about the implications of climate change in the future,” said Aisha Al-Sarihi, an Oman-based researcher at the Middle East Institute at the National University of Singapore. “If we continue to expand and expand, it means we need more energy, more water and more electricity, especially for cooling. But there are limits, and we see those limits today.”

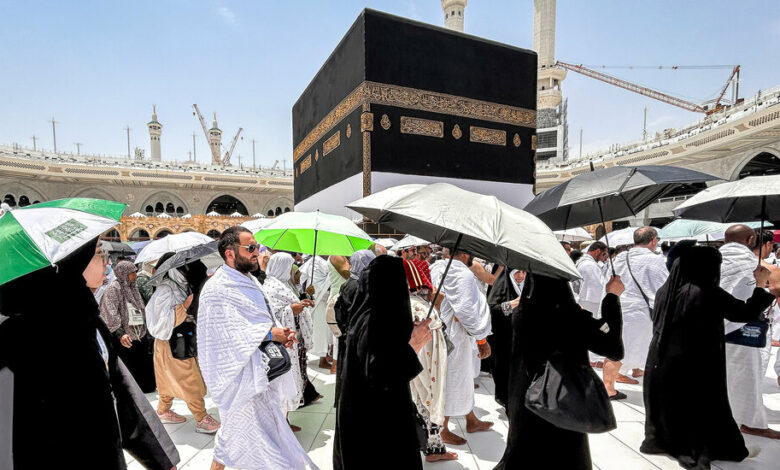

The threat of extreme heat became apparent this week when Saudi Arabia announced that more than 1,300 people had died during the annual Hajj pilgrimage in Mecca, including at least 11 Americans. Saudi officials said most of those who died had made the trip without permits that would have given them access to heat protection, leaving them vulnerable to temperatures that sometimes exceeded 120 degrees.

The deaths raised questions about how Saudi Arabia managed the event, which drew more than 1.8 million Muslims to the holy city of Mecca.

The kingdom and other Gulf countries are pouring huge amounts of their oil wealth into efforts to boost their economies and climb the list of popular global destinations.

Saudi Arabia is building super-high-end resorts on the Red Sea coast and a futuristic city called Neom in the northwestern desert. Qatar hosted the Men’s World Cup last year and has secured other international sporting events and trade fairs. The United Arab Emirates hosted a splashy World Expo and its business-friendly policies have helped it become a playground for the hyper-rich.

But these countries face major environmental challenges.

They have all had scorching hot summers for long periods, but scientists say climate change has already made the season longer and hotter – a trend expected to accelerate in the coming decades. Some projections warn of weeks of heat waves with temperatures of up to 132 degrees in the second half of this century. Such high temperatures can endanger human lives.

Gulf States, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman and Qatar, are among the most water-stressed countries in the world, meaning that available water can barely meet demand. This requires them to import water or remove the salt from seawater, an expensive and energy-intensive process.

Many Gulf countries have announced sweeping environmental initiatives aimed at reducing carbon emissions, greening major cities and developing climate-friendly technologies. They have also invested heavily in efforts to limit the dangers of extreme heat — often with measures that other Middle Eastern countries struggling with high temperatures, such as Egypt, Yemen and Iraq, cannot afford.

But money is not always enough.

This month, parts of Kuwait, a major oil exporter, were hit by sudden power outages. In some areas, traffic lights went out and people became stuck in elevators as temperatures rose to 125 degrees.

Authorities blamed rising energy demand, which overwhelmed power plants. To reduce the tax, the government has imposed power outage during the hottest hours of the day, forcing people to look for alternative air-conditioned spaces.

The summer heat drastically restricts life in Kuwait, changing the times at which people work and sleep and forcing those who can afford it to stay in air-conditioned environments.

Fatima Al Sarraf, a general practitioner in Kuwait City, said she used to run long distances in winter, but in summer she had to run on a treadmill or go to the mall to get her daily steps.

“I don’t go outside at all,” said Dr. Al Sarraf, 27.

She fears for the future.

“If the temperature continues to rise, especially in the summer period, Kuwait is expected to become uninhabitable,” she said. “This change will definitely affect future generations.”

Other countries appear to be managing the heat better, although they still face challenges.

Qatar has used the wealth generated by its status as one of the world’s largest exporters of liquefied natural gas to cool outdoor spaces even during the hottest hours of the day. Stadiums it built for the 2023 World Cup were equipped with outdoor air conditioning so they could be used year-round. One city park in the capital Doha has a air-conditioned running trackand a outdoor cooling system was recently unveiled at a popular open-air market.

“There is a cooling ecosystem,” said Neeshad Shafi, a Qatar-based non-resident fellow at the Middle East Institute. “Everything needs to be cooled – there are more cooled parks, more cooled gardens, more cooled shopping areas and more cooled souks every day.”

But these technologies are expensive – and even more so to deploy over large areas.

“You can’t cool everything in a country,” Mr Shafi said.

Nor are the protections such technologies provide routinely available to the most vulnerable, including the millions of migrant workers who do everything from construction to gardening in the Gulf. Many have no choice but to work outdoors, and studies have shown that working in extreme heat increases accidents and can damage the body.

To protect outdoor workers, Qatar and other Gulf states have imposed a ban on most outdoor work during the hottest parts of the summer days. This year, Kuwait extended this protection to motorcycle delivery drivers who had been roasting in their helmets on the sweltering asphalt.

But temperatures are also stifling at night and as countries warm, governments may need to extend work bans or take further measures.

“These countries are moving fast, but the temperature is moving faster than them,” Mr Shafi said.

Rising temperatures could also hamper Saudi Arabia’s dramatic development plans. Will tourists flock to new luxury resorts when it’s too hot to swim comfortably in the Red Sea? Will enough people want to move to the capital Riyadh to double its populationwhile daytime temperatures there regularly exceed 38 degrees Celsius for a large part of the year?

And as the kingdom heats up, it becomes even harder to hold the Hajj safely.

The pilgrimage and its associated rituals involve spending many hours outdoors and walking long distances. Since the timing of the Hajj is based on the lunar calendar, it progresses gradually throughout the year and cannot be rescheduled.

The Saudi government has invested billions of dollars to protect pilgrims, providing elaborate umbrellas, water mist fans and air-conditioned shelters to protect against the heat.

But scientists warn that temperatures will be even higher the next time the Hajj takes place in summer, from the mid-2040s. recent research warned that future pilgrims would be exposed to heat exceeding the “extreme hazard threshold” unless “aggressive adaptation measures” were taken.

Tariq Al-Olaimy, director of 3BL Associates, a sustainable development consultancy in Bahrain, said he saw the deaths on this year’s pilgrimage as “a wake-up call” because they highlight both the successes of heat protection and the risks for people without this protection.

“The hajj lesson is that if this is not a priority for the entire population, there will be fatal consequences,” he said. “But there is also the lesson that if there is good and adequate thermal management, we cannot thrive, we survive.”

Yasmena Almulla contributed to reporting from Kuwait City, Kuwait.