‘Right-sizing’ Manchester United – what it’s like when INEOS ‘rips off the Band-Aid’

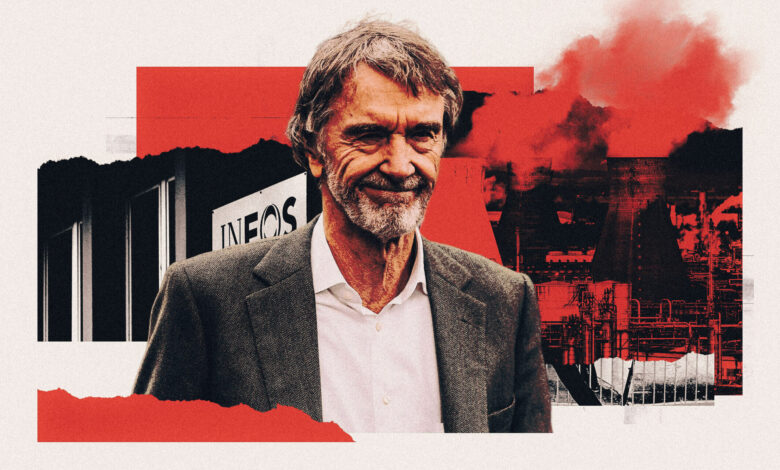

This month, Manchester United’s interim chief executive Jean-Claude Blanc informed staff of the club’s intention to cut 250 jobs before the start of the season as part of attempts by minority owner Sir Jim Ratcliffe to trim costs at Old Trafford.

Blanc’s address to staff was short and to the point. After he stopped talking, the room fell silent. The mood was understandably solemn, even if the news was not especially surprising.

At the last count, in March, United’s workforce stood at an average of 1,144 monthly employees — the largest in the Premier League.

INEOS hoped to shave 20 per cent of a workforce and, in May, the club’s non-football staff were effectively presented with a voluntary redundancy package, offering employees the chance to receive an early annual bonus if they agreed to walk away. Few took the club up on their offer.

As a result, these job cuts were half-expected. Only the Manchester United Foundation, the club’s charity, is ring-fenced. All other departments and levels within the club are affected.

The redundancies are part of wider cost-cutting measures across the club after United appointed consultancy firm Interpath Advisory to identify “non-essential” activities and review where savings could be made.

Blanc confirmed the job cuts that many had been expecting (Ash Donelon/Manchester United via Getty Images)

INEOS has subsequently cancelled company credit cards and insisted staff contribute to their own expenses for the FA Cup final in May. At a recent leaving do for outgoing members of senior management, the club did not put any money behind the bar.

This swathe of redundancies, however, will have the most profound impact on the lives of the ordinary people who work at the club, with between a quarter and a fifth of roles expected to go. It is a grim state of affairs but, as those who have previously worked for INEOS know well, the drive to cut costs upon taking control of a business can be uncompromising.

In the world Ratcliffe and his fellow INEOS executives inhabit, they might call it ’right-sizing’ — essentially, restructuring a company to better meet its business needs.

That is a rather euphemistic way of describing the swingeing cuts announced at Old Trafford and the changes to working conditions that United’s minority owner has insisted upon since taking control of football and business operations.

Those with experience of INEOS’ approach to right-sizing recognise the Ratcliffe playbook of initiating a painful period of cost-cutting to create a leaner, more efficient organisation down the line.

“You rip off the Band-Aid early if they’re losing money,” says one former employee — who, like others in this piece, spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect relationships — who sympathises with the logic. “His whole mantra has always been to strip out the costs and run a very decentralised company. It actually works well.”

That was the modus operandi following INEOS’ $9billion (£6.9bn) buyout of BP’s petrochemicals sidearm Innovene in late 2005, which elevated Ratcliffe’s fledgling company from being a relatively minor player in the petrochemicals industry to the third-largest of its kind in the world.

Executives were given a tour of Innovene’s state-of-the-art global headquarters in downtown Chicago, which opened only seven months earlier. Yet one of Ratcliffe’s first acts was to shut that headquarters down, as well as other offices in Lisle, Illinois and Staines in the south of England.

This was part of a restructuring programme to bring Innovene into line with INEOS’ “business strategy”, according to the company’s accounts.

Over the following seven years, initially across the corporate side of the business and then at plants and refineries, INEOS spent approximately €220million (£184.7m, $239.9m) in an attempt to cut costs, largely through severance and early retirement payments to former employees.

And so from the very start, Innovene employees were conscious that INEOS would always be watching the bottom dollar. Similarly to measures taken at United, corporate credit cards were taken away and staff were warned not to spend liberally on basics, such as office supplies.

Working practices were also scrutinised. Ratcliffe found the company operated on a 9/80 schedule — staff would work 80 hours over nine working days, earning themselves every other Friday off. As he was used to every member of staff being available every day of the working week, Ratcliffe is said to have “chafed” and “chuntered” at that approach.

Ratcliffe breaks meetings to exercise (Justin Tallis/AFP via Getty Images)

INEOS’ sceptical attitude towards the benefits of working from home comes as no surprise to those who have worked in its typically open-plan offices, which are designed to encourage collaboration between colleagues and the sharing of ideas and information. As a result, even senior executives have been stationed among the rank and file rather than safely cocooned in separate workspaces.

Such measures are not always popular. Those not prepared to adapt to INEOS’ way of working typically move on, only aiding the company management’s attempts to right-size. The message is: “You’re either in this and understand what the mission is or it’s not for you.”

That much has been evident during INEOS’ early months at United. Plans to end working from home were opposed by the club’s interim chief executive Patrick Stewart, whose departure after more than 18 years at Old Trafford was confirmed in April.

Stewart was standing in for previous chief executive Richard Arnold, another casualty of INEOS’ changes. Football director John Murtough, chief financial officer Cliff Baty, communications chief Ellie Norman and alliances and partnerships chief Victoria Timpson have also left.

Given Ratcliffe’s taste for running lean, agile and cost-effective organisations, some staff at INEOS questioned the company’s initial ventures into the world of sport, believing that spending billions on football, sailing and motor racing pursuits was at odds with that business ethos.

The importance of sport to Ratcliffe is hard to understate, though, and difficult to escape for those working within his vicinity. He encourages his employees to lead a healthier lifestyle, to the extent that one floor of INEOS’ Swiss headquarters in Rolle was refurbished to include a fitness centre and free bikes.

There have even been occasions in which Ratcliffe has cut business engagements short to exercise. “You would be in a meeting with him and then all of a sudden, it was time for him to go work out,” says one source. “You’d see him running by.”

That would usually only happen when Ratcliffe’s feet were metaphorically, if not physically, under the table. An initial, hands-on approach tends to give way to delegation, once a senior management structure he can trust is in place beneath him.

United’s pursuits of senior executives have been the story of INEOS’ first months in charge, with incoming chief executive Omar Berrada set to start work alongside sporting director Dan Ashworth, technical director Jason Wilcox and interim director of recruitment Christopher Vivell. Away from football, United are also expected to appoint a chief business officer to report to Berrada.

United have hired several executives, including Wilcox, but plan to scale back overall staff numbers (Matt McNulty/Getty Images)

From a cold business perspective, judging whether such measures have succeeded for INEOS in the past is not straightforward from public accounts as Innovene was subsumed into the wider company.

Innovene made a pre-tax profit of $1billion in the year leading up to INEOS’ purchase, having previously recorded a loss of $133million in 2004. After the purchase, INEOS’ profits rose to a high of €325.2million in 2007, before crashing to a €735million loss amid the economic downturn in 2008.

Some former employees argue those losses could have been worse and commend Ratcliffe for right-sizing at the right time, therefore being better able to stomach the blow of 2008 than its rivals.

“They were right-sized in the number of people they had,” says one person familiar with the organisation. “That was to be commended because LyondellBasell and Shell and others, lots of them had huge layoffs in the 2008 downturn.”

INEOS spent approximately €143million more on restructuring in the first two years following the Innovene purchase than it did between 2008 and its brief return to profitability in 2011.

Yet the company was only consistently recording profits again from 2015 onwards. By that time, INEOS had emerged from one of the most infamous disputes in the modern history of British industrial relations.

As part of the Innovene deal with BP, INEOS took charge at Grangemouth — the oil refinery complex that is a key component of Scotland’s economy, responsible for an estimated four per cent of Scottish GDP and approximately eight per cent of the nation’s manufacturing base.

Upon INEOS’ arrival in 2005, unionised workers at Grangemouth were warned by their counterparts with experience working for INEOS of the parable of the apple and the dinner money.

“The parable goes like this,” wrote Mark Lyon, a convener for trade union Unite at Grangemouth, in the Battle for Grangemouth: A Worker’s Story, an account of the industrial disputes during INEOS’ first eight years of managing the site.

“If you give the school bully your apple, they want your dinner money. If you give them that, they want your bus fare home. If you give them that, it’s your designer trainers. They will not stop until they have taken possession of your grandmother’s stair lift. We thought our colleagues must be trying to wind us up.”

Ratcliffe at Grangemouth, the heart of a huge industrial dispute (Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images)

Although far from perfect, relations between workers and the management of BP were relatively amicable. In 86 years of operations at the refinery, production had not once been shut down due to industrial action — but within three years of INEOS’ buyout, workers were on a picket line.

In early meetings between company executives and union officials, INEOS made it clear that it planned to close the final salary pension scheme — which paid out pensions defined by an employee’s salary upon retirement rather than their contributions.

In 2008, INEOS announced its intention to close the scheme to new entrants, arguing it was unsustainable. Unite contested that the scheme was fully funded in surplus and that the company was abolishing it on purely political grounds.

Around 97 per cent of Unite members at the refinery voted in favour of strike action, which took place over two days in April. Almost half of the UK’s North Sea oil production was halted as a result. When talks reopened, INEOS took the pension amendments off the table at an estimated cost of £120million.

It was a victory for the union but only the start of a bitter war that lasted more than five years, pitting the company against its workforce.

One former Grangemouth worker sums up INEOS’ attitude towards its employees on-site at the time: “If we could run it without anybody being there we would, but because you’re there we’ll have to pay you, I suppose, and have certain safety arrangements. ‘Contempt’ would be the word.”

Ratcliffe’s decision to go on the offensive and send an all-staff email complaining about untidiness at Old Trafford and Carrington in May may ring a bell with those involved in the Grangemouth disputes.

During the 2008 dispute over pension schemes, Ratcliffe sent an email outlining ‘strike consequences’ — essentially, the price workers would have to pay for their defiance, which included abandoning the bike-to-work scheme.

Ratcliffe is overhauling many areas of United as he has done at previous businesses (Manchester United/Manchester United via Getty Images)

Sent without prior consultation, during a pause on hostilities to seek a way forward, Ratcliffe’s note threatened to escalate matters but talks between union representatives and management took place and the proposed changes did not come to pass.

“He wouldn’t send out constructive stuff,” says one person familiar with the situation. “He’d only send out stuff that was absolutely bonkers and would upset everybody.”

Negotiations with INEOS could be high-stakes affairs of all or nothing. Many of United’s remote-working staff were effectively offered a choice of relocating or taking up voluntary redundancy — and Grangemouth workers were presented with similar ultimatums during talks with management.

“You get management sitting across a table saying, ‘I’ve not got any more to give you’, then when you say something, they maybe put half a per cent on,” says one person with experience of the situation. “But I think they were drop-dead serious on it. Give them that or nothing else.”

The most infamous example came during a 2013 dispute, sparked by the suspension of union leader Stevie Deans over allegations of conducting Labour Party business on company time. Ratcliffe was, simultaneously, questioning Grangemouth’s long-term financial viability in public.

At the height of the dispute, after workers rejected the company’s survival plan that would cut the pension scheme fought for in 2008 and much more, INEOS announced its intention to close Grangemouth’s petrochemicals plant, wiping out 800 jobs and putting thousands more across the rest of the site at risk.

Unite relented and embraced the survival plan “warts and all” to protect jobs at the site. Deans subsequently resigned from his position with INEOS before the outcome of his internal disciplinary case.

“This move by INEOS was designed to cut right to the heart of human frailty,” wrote Lyon of the threatened closure. “The fact that the company was prepared to go to such lengths is still a source of sickening disbelief.”

As a result of the bitter dispute, the prime minister at the time, David Cameron, announced plans for an independent review of trade union laws, led by Bruce Carr KC.

Unite refused to cooperate with the review, labelling it a politically-motivated “Tory stunt”. INEOS told Carr that union tactics that could be classed as intimidation or bullying should be criminalised, citing protests outside the residential homes of Ratcliffe and other senior INEOS managers.

“The common theme was as follows,” claimed INEOS’ submission. “The protestors would arrive waving banners and, in many cases, with a very large inflatable rat. They would play loud music and challenge passers-by to support the union by passing out leaflets.”

After also receiving a submission from Hampshire Constabulary, the Carr review concluded that there was no evidence to suggest that the protests it assessed “were anything but peaceful”.

Ratcliffe leaves talks with the unions in 2008 (Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images)

More than a decade on, people spoken to by The Athletic on both sides say that relations between INEOS and Unite have improved, with the company and the union having learnt lessons from the past. The relationship is described as “mature” and “in the right spirit”, while meetings with Ratcliffe and other company executives are said to be amicable and reach constructive outcomes.

“People don’t want to go back to (the disputes) because it was so damaging,” says one union representative, who points out that oil and gas companies and trade unions increasingly find themselves working together to protect jobs, amid pressure from governments chasing environmental targets.

INEOS argue that investing £12billion across its four main UK sites over the last quarter of a century has secured more than 5,000 jobs. Yet Grangemouth’s future is almost as uncertain as a decade ago.

In November last year, Petroineos — the joint venture between INEOS and China’s state-backed PetroChina — announced its intention to eventually cease operations at the site’s oil refinery, potentially next year, citing global market pressures, dwindling demand, the site’s age and the transition towards greener energy.

Despite plans to convert the facility into a fuel import terminal, almost 400 jobs are at risk. Discussions between the company, unions and the government are ongoing, with Prime Minister Keir Starmer describing securing jobs as a priority.

Manchester United’s workforce is not broadly unionised, but the club insist that they are following the strict process that governs redundancy programmes, including the appointment of employee representatives.

This month, United announced their results for the third quarter of the financial year, revealing a loss of £76.9million up until the end of March. Pre-tax losses were even higher — totalling £89.2million up until the end of March.

That figure is the starting point for calculations under the Premier League’s profitability and sustainability rules, cited by INEOS as one reason cost-cutting measures are necessary.

United last posted an end-of-year profit in 2019. Over the four and a half years since, their total losses stand at £331.1million.

Part of that is a legacy of Covid-19, which heavily depleted the club’s cash reserves — down from £307million pre-pandemic to just £67million now. It is also down to how the Glazer family ran the club, loading United with debt following their £790million takeover in 2005 and leaving it to pay the bill.

United were spending more than £1million in interest payments each week during the third quarter of last season. Put it another way: the initial £420,000 fee received from Girona for Donny van de Beek’s transfer this month would theoretically cover this week’s payments up until sometime on Wednesday morning.

Few owners would look at United’s finances and conclude that nothing needs fixing — but one of the key takeaways from Ratcliffe’s first meeting with staff at Old Trafford in January was his insistence that he had not invested in United to make money.

Ratcliffe might counter that he did not intend to lose money either but the message that footballing success would be prioritised above all else was one reason staff left that first meeting with INEOS with a sense of renewed optimism.

And yet as United’s minority owner pursues that objective, many of those same staff left that most recent meeting fearing for their futures.

(Top photo: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)