The Blind Side of Sports Stories

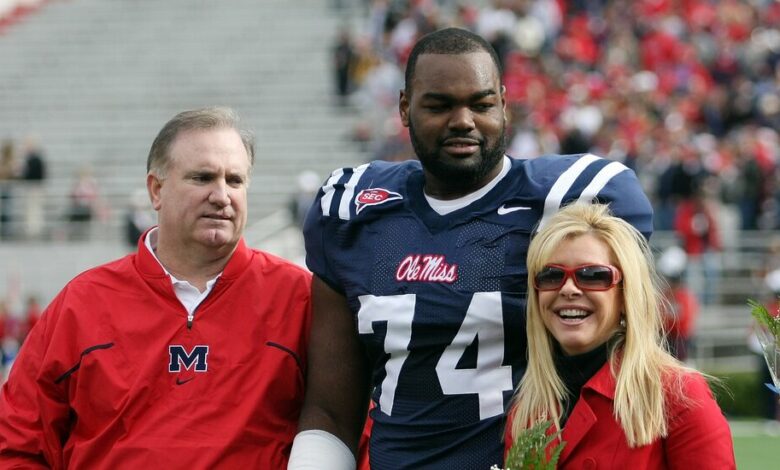

Of course, America loved “The Blind Side,” the 2009 film about a homeless and down-on-his-luck black teenager rescued from a bleak future by a wealthy white family. The film was based on the true story of the Tuohy family, led by Sean and Leigh Anne, who took in future NFL player Michael Oher and proudly raised him as he went to college and beyond.

It’s the kind of story we’ve come to expect in the sports world, one that reasserts our beliefs about the power of sports to create lifelong bonds, help participants overcome adversity, and build character. It’s also a simplified account of race in America, one that hinges on the idea that white people can be magically redeemed by coming to the aid of a black character.

Audiences lapped it up. The film grossed over $300 million and Sandra Bullock won an Oscar for her portrayal of Leigh Anne Tuohy, the self-assured beauty of the New South.

But “The Blind Side,” based on Michael Lewis’ best-selling book, portrays a complicated reality in the most digestible format. This week, surprising news of a lawsuit filed by Oher against the Tuohys spurred many to reconsider the film, seeking answers to questions raised by the legal claim that were overshadowed by the film’s comfortable, tidy narrative.

Oher is suing the couple for a full accounting of their relationship. He claims that when he thought he was being adopted at age 18, the Tuohys urged him to sign a conservatorship that gave them the control to make contracts on his behalf. He says the family bond, warmly depicted in the film, was a lie and that the Tuohys enriched themselves at his expense.

The Tuohys have defended their actions, saying in a statement that the conservatorship was a legal necessity so Oher could play football at the University of Mississippi without jeopardizing his eligibility.

In a story with at least four versions – Lewis’s, the movie studio’s, Oher’s, and the Tuohys’ – it’s nearly impossible to tell who’s telling the truth.

Until this week, I have to admit that I had never seen “The Blind Side.” I had avoided it on purpose. I’m wary of movies that rely on simple racial clichés — a fatigue that started when I was a kid, when so many of my black heroes died at the end of movies so white heroes could live.

News of Oher’s lawsuit convinced me that it was time to crash on the couch and take in the film, with the benefit of fourteen years of hindsight—fourteen years in which race and sports have once again emerged as essential platforms for investigating US interests. issues.

My assumptions were proven correct early in the film, as Oher’s character began to take shape. As the story unfolds, he’s painted as a lost cause before he meets the Tuohys and gets into a wealthy Christian school in Memphis. The film portrays him in simple terms: as a body, first and foremost — a giant black teenager whose IQ, we’re told, is low, and who has no idea how life works in worlds not awash in poverty and despair.

The Oher of the film, especially in the beginning, has little agency and no real dreams of his own. When I saw that, it felt like a punch in the gut. “What?” I muttered. “There is no way that characterization is true.”

The Baltimore Ravens selected Oher in the first round of the 2009 NFL draft. No one gets that far in the game without a foundation of years of motivation and training, which lends credence to Oher’s long-held criticism of his portrayal in the film. He’s an intelligent person, Oher has said time and again, and he was an accomplished football player long before he met the Tuohys.

Not one who needed the Tuohys’ young little son, Sean Jr., to teach him the game the easiest way — using bottles of condiments to demonstrate formations and plays. We look at Sean Jr. in a park, enjoying training a clueless Oher.

The film also shows how the Tuohys use sports to help Oher develop self-confidence, enter a world of prestige and wealth and eventually attend Ole Miss, the couple’s alma mater, where Sean Tuohy was once a basketball star.

Oher protects Leigh Anne Tuohy when they dare to venture into the neighborhoods where he grew up — “That horrible part of town,” she says. He saves Sean Jr.’s life when the two are involved in a car crash, using his massive arm to shield the young boy from the force of an airbag. When Oher struggles on the practice field while learning the game, Leigh Anne Tuohy jumps in from the sidelines and gives him a stern instruction: He must protect the quarterback the same way he protected her and her son.

“Protect the family,” she urges.

A lesson Oher receives from a feisty white woman as if he were a first-grader (or a servant) is a turning point. Oher begins to transform from a football neophyte raised on the streets to an offensive lineman with the strength of Zeus, the agility of Mikhail Baryshnikov and the size of an upright piano.

We soon see him playing in a match, where he has to deal with aggressive and racist comments from an opponent who initially gets his way with an inexperienced rival.

Suddenly Oher snaps. He doesn’t just block the opponent: Furious, Oher lifts him up and drives him across the field and over a fence.

“Where did you take him, Mike?” his coach asks as Oher stands on the sidelines.

“To the bus,” Oher says dryly, his tone innocent and childlike. “It was time for him to go home.”

By the end of the film, the transformation is complete. We learn that Oher’s IQ has improved to an average level under the tutelage of a wealthy white family! We watch him become a high school champion! We watch a parade of coaches — real coaches, playing themselves in the film — fawn over Oher as they try to convince him to apply to their school.

It’s hard to discern Oher’s motivations or his cunning from the way the film tells it, because he’s still portrayed as a prop — quiet, docile, a young man who, for the most part, does what his newfound family tells him to do. Which, by the way, makes it hard to know the truth of his trial all these years later.

What we do see in the film is that he shines in college and in the pros. There he is in the NFL, in his Baltimore Ravens gear. He had made it to the sports promiscuity land and the Tuohy family was there for him.

This movie had everything.

The oversimplified cliché about race and class in America that Hollywood has always propagated.

The simplified story that uncritically celebrates sport and its purity, the way it can change lives, always for the better, by turning rough diamonds into jewels. The dark side of sport — the deceit, the lies, the broken promises that can come from both sides in this legal battle — never penetrates the fairy tale.