The Energy Grid Has a Problem. Your House Could Help Save It

It’s not apparent from the curb what makes the Hillside development at O’Brien Farm in South Burlington, Vermont, different from any other tract of homes being built around suburban America.

The street I pull onto looks like an evolutionary chart of suburbia: At one end stand complete, freshly painted 2,500-square-foot houses with well-manicured lawns and landscaping. Moving northward along Leo Lane, I see some homes missing finishing touches, then some missing garage doors, then wooden skeletons. Finally, there are bare patches of dirt. I get stuck behind a dump truck.

I had to look — and listen — closely to see what makes this development a glimpse of something new. It’s not just an innovative way of building a community. It’s a way of future-proofing the American electric grid through the clean energy transition and climate change.

Once people move in, these homes will work together with others from across the state to form a virtual power plant, ensuring consistent power and saving both the grid and residents money. In some programs like these, people have negative power bills. That’s the promise of a virtual power plant.

Touring the model home, the first thing I notice is the sounds. Outside is a busy construction site, filled with the noise of front-end loaders and that dump truck. Inside the house, I can’t hear it. These homes are built with enough insulation to keep comfortable air inside and the cold New England winter — or, as was the case when I visited, a hot and humid New England summer — on the outside. I can’t feel the heat in here. It’s a little chilly.

Next up: the appliances. In the kitchen, there’s an energy-efficient induction cooktop. An iPad sits on the counter tuned to the SPAN app, which provides control over every circuit in the home and a view of the home’s energy use. For those who own an electric vehicle, in the garage is a SPAN EV charger, which comes with the house.

In the basement, a utility closet houses a large Mitsubishi Electric heat pump air handler — it’s the heater in the winter and the air conditioner in the summer. It’s all-electric and barely makes a sound.

The water heater, also powered by a heat pump, is in another closet. On the wall across from it is the SPAN smart electrical panel controlled by that iPad in the kitchen. Next to that: three Tesla Powerwall batteries, packing 40.5 kilowatt-hours of energy storage, enough to get a household through a lengthy blackout.

Those Powerwalls are also wired to the 8kW Qcells solar panel system on the rooftop. That app on the kitchen counter shows just how much power this house has gotten from the panels so far today, and how much it’s had to buy from Green Mountain Power, the electric utility that leases out the Powerwalls.

The model home of the Hillside at O’Brien Farm development in South Burlington, Vermont, offers a glimpse at an all-electric, connected energy future.

This entire home is a collaboration between GMP and the developer, O’Brien Brothers. Every house in this development will come with a system like this, resulting in an entire neighborhood of energy-efficient homes equipped with solar panels, backup batteries and all-electric appliances.

One thing I can’t see: There isn’t an inch of fossil-fuel pipe in this soon-to-be neighborhood. The gas company would’ve put it in for free, but O’Brien Brothers said no thanks. The people who move in here will know their energy use isn’t contributing to the fossil fuel emissions driving climate change.

For the power company, the neighborhood includes some ways to save energy and money. But perhaps most importantly, this neighborhood can help the country’s increasingly stressed electric grid. That’s because all of those batteries and EV chargers don’t just stand alone — they’re connected, and when the grid needs it, GMP can put them to use with a few clicks of a mouse.

Across the country, electric utilities are turning to virtual power plants, or VPPs, to bridge the gap between spikes in electricity demand and the limited generation and infrastructure currently available. These programs can do the work of far more costly and dirty natural gas power plants, and they can be activated in seconds. As the US power grid faces massive challenges, these VPP programs are making individual customers — their batteries, their thermostats, their EV chargers — part of the solution.

Green Mountain Power likes to refer to its VPP, which includes more than 3,000 home batteries across the state, as a real power plant. “This is our largest generating facility, all of this network of stored energy,” says Kristin Carlson, GMP’s vice president for strategy and external relations. “It’s obviously a great experience for the people who live in the homes, but then it’s benefiting all of our other customers as well.”

The clean energy transition is changing the way we generate electricity, and climate change is making it harder to keep the lights on through increasingly severe weather. American consumers face rising power bills as infrastructure costs and energy supplies push up the price of electricity and as they use more power to charge their EVs or run all-electric heating and cooling, all areas where fossil fuels are on the way out.

It’s easy to think of solar panels and home batteries as routes to energy independence, to cutting oneself off from the grid and its vulnerabilities and going it on your own. But what if the solution to both of these problems isn’t energy independence but energy interdependence? A report last year by the US Department of Energy estimated that deploying 80 to 160 gigawatts of VPP capacity by 2030, on top of the existing 30 to 60 GW, could save $10 billion in annual grid costs.

From New England to Hawaii, VPPs are an increasingly important item in the toolbox of the US electric system. So why isn’t your home part of a VPP yet? I talked to energy experts, executives, policymakers and consumers to find out. Here’s how they work, why the old grid isn’t cutting it anymore and what you need to know about your home’s electric future.

Inside a virtual power plant

Green Mountain Power’s headquarters is in Colchester, a short drive from Burlington, and inside it is a control room. Across one entire wall is “The Grid,” visualized.

A massive diagram, like a high-tech subway map, shows the names for each generator and substation (one is simply “Ben & Jerry’s”) and the controllers sitting at monitor-laden desks keep a close eye for lines that are damaged or out of commission. This is what I picture when I think about the grid.

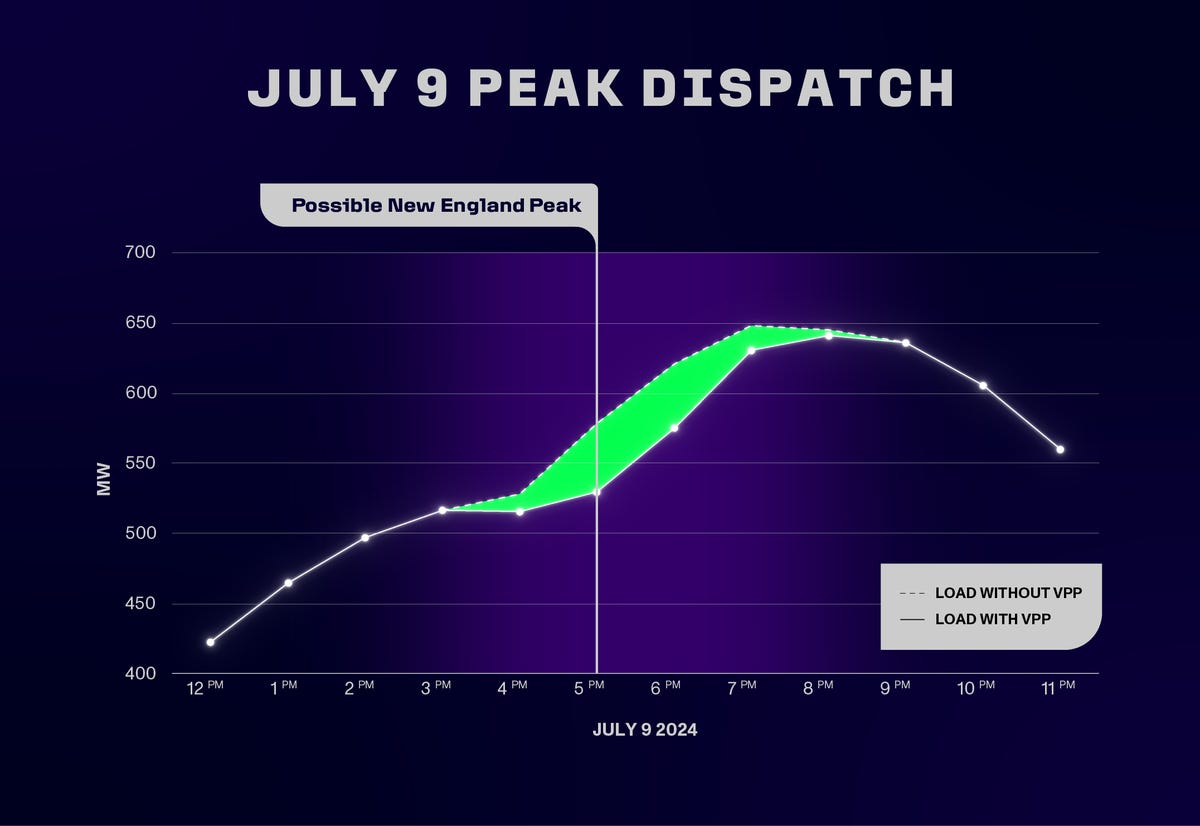

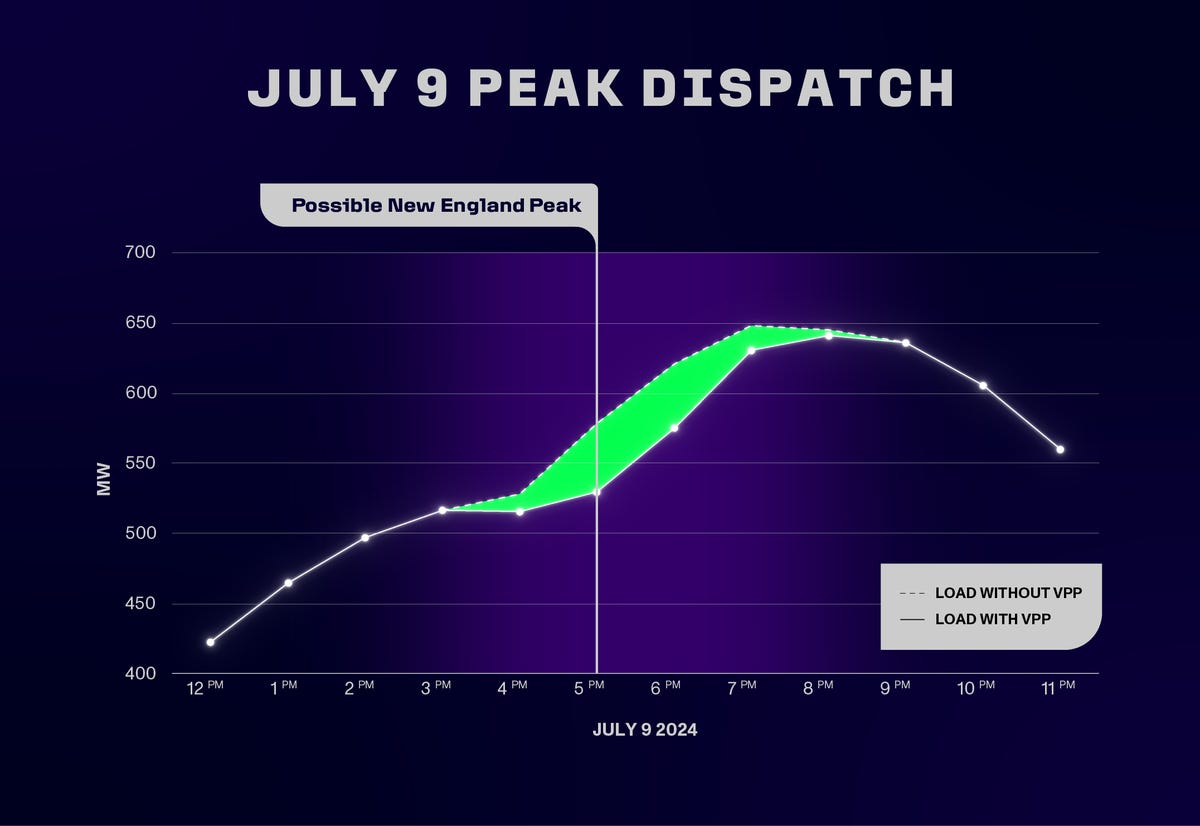

This chart, showing the energy load for Green Mountain Power in Vermont on July 9, 2024, illustrates the savings and reduced peak from use of the utility’s virtual power plant.

The VPP? It’s not here. It’s on the other side of the secure door and bulletproof glass that guard the control room. It’s at a desk a few feet away, on the laptop of Maddy Murray-Clasen, GMP’s innovation project manager.

From a program called Virtual Peaker, Murray-Clasen monitors and controls all of the batteries and EV chargers in the company’s VPP. When her colleagues predict an extra oomph of power might be needed, she schedules an event for that day. It could be a particularly hot summer day, when late afternoon and early evening might see Vermonters get home from work and simultaneously blast their air conditioners.

When demand is high and supply is low like this, the batteries can discharge power onto the grid. A homeowner’s Tesla Powerwall, for example, will release all but 10% of its potential stored energy, leaving enough for backup in case of an outage. That’s unlikely to be needed — this whole system is designed to prevent those outages in the first place.

For an EV charger, GMP will ask customers for permission to turn off their charger during a grid event, meaning someone mindlessly charging their vehicle won’t be contributing to a strain on the system. You’d have the choice to opt out of this, although instead of paying the usual discounted rate you’d get for charging your EV, you’ll have to pay the higher standard electric rate. That’s rare, occurring less than one-tenth of 1% of the time, Murray-Clasen says.

In the energy industry, the traditional systems that provide emergency power to the grid are known as peaker plants. These facilities, usually powered by natural gas, are activated fairly quickly when energy is needed. They may sit idle for much of the year, jumping into action only on the most demanding days. They’re expensive to build and maintain, and when they’re used, they’re belching climate-warming fossil fuel emissions.

The VPP, on the other hand, is using your home’s batteries to deal with those peaks. And Green Mountain Power’s generation is entirely carbon-free.

GMP has never actually had to switch on its VPP unexpectedly in an emergency — the utility usually know at least a day in advance when it’ll be needed — but I want to know how quickly it could be activated (for context, a peaker plant can turn on quickly, but not instantaneously). Murray-Clasen thinks about it and runs through how quickly she could click everything. “Less than a minute to log in and click go,” she says.

That kind of speed might be necessary, considering all the hurdles facing our energy system.

The “grid” is controlled from screens like this one at Green Mountain Power in Vermont.

What’s wrong with the grid we’ve got?

It’s been called the world’s largest machine. Hundreds of thousands of miles of wires connecting everything from the Hoover Dam to your home and the coffee shop down the street. It’s dotted with substations and transformers and strung with transmission lines stretching as far as the eye can see. When part of it fails for even a few hours, that makes the news, and if part of it fails for a longer period, the effects can be deadly. The prospect of the whole thing failing at once keeps national security experts up at night. It cost more than a trillion dollars to build, and this machine, the US electric grid, has problems.

“Today, it’s very clear that we don’t use the machine efficiently,” Jigar Shah, director of the US Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office, told me last year. “There’s no other machine in the world that you spend a trillion dollars on that you’re not trying to get the most out of it.”

But the problems stretch beyond inefficiency. For about two decades, the grid has been sufficient. It’s had its struggles, but it’s largely been up to the task. That’s because, each year, we’ve asked about the same of it as we did the year before. That’s changing, and fast.

“We’ve underinvested in the grid for many years in the country for many, many reasons, and it’s coming home to roost now,” says Mark Dyson, managing director with the Carbon-Free Electricity Program at the clean energy think tank RMI.

The problem is on the mind of energy experts from the federal government down, and one of many potential answers comes in the form of better coordination among the appliances in your homes and offices. A VPP is relatively cheap and can be easily scaled, but to understand its potential role, you have to grasp the scope of the grid’s issues.

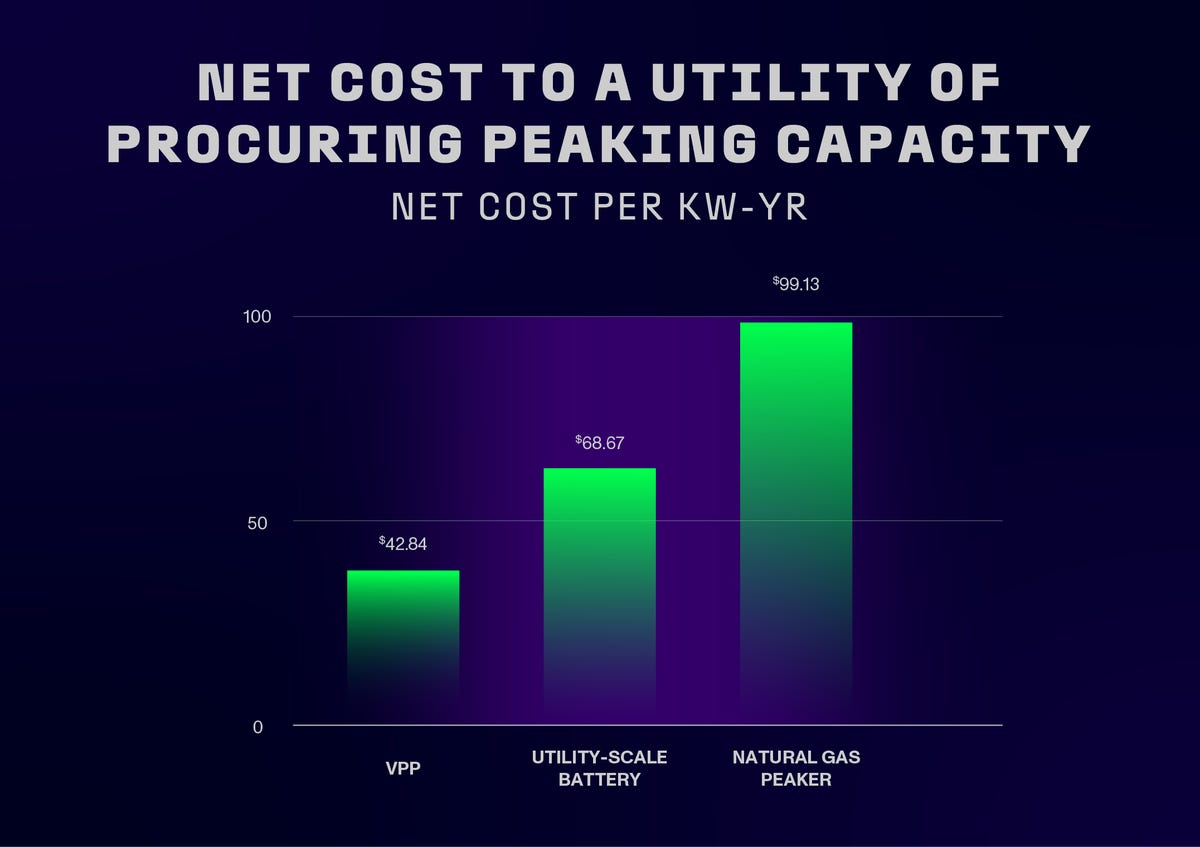

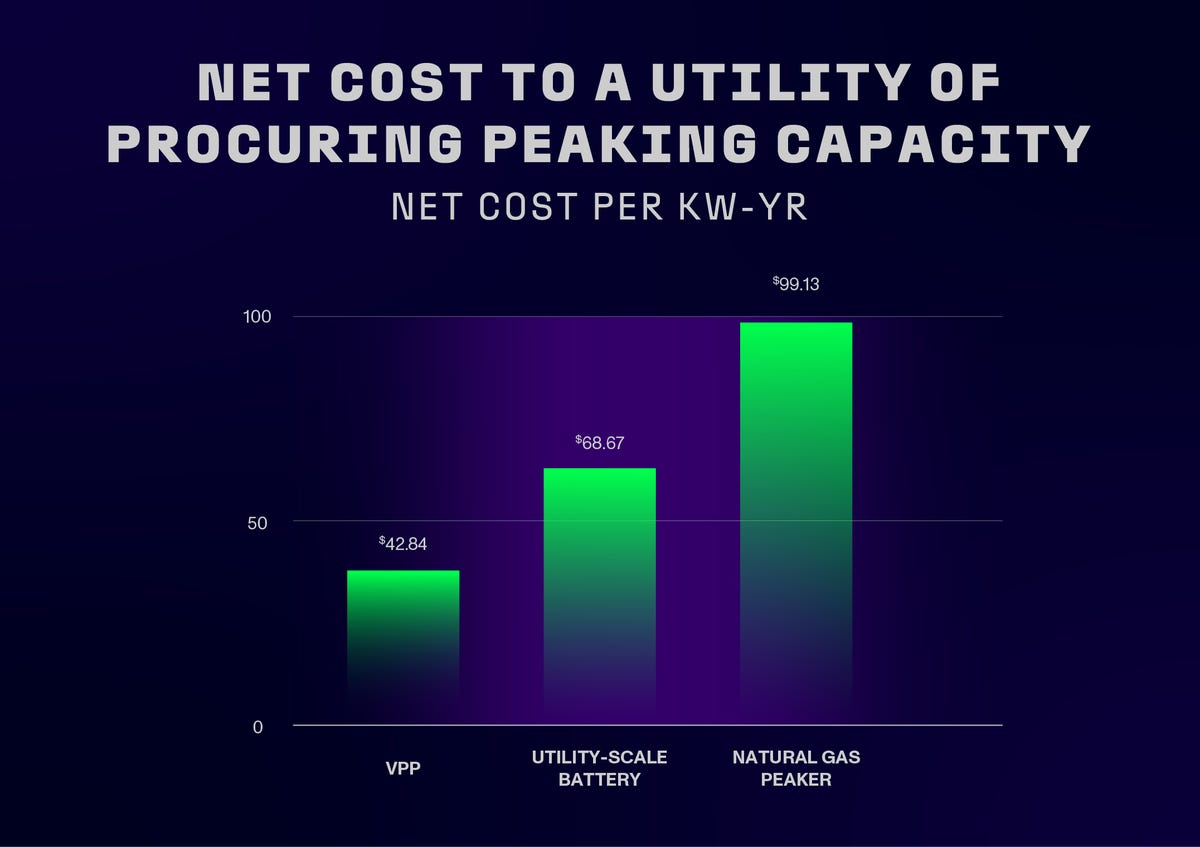

Estimates from the Department of Energy found that, when costs and benefits were considered, a virtual power plant can provide electricity at a demand peak at a much lower cost than a natural gas peaker plant.

The changing ways we generate electricity

In 2023, fossil fuels still accounted for 60% of US utility-scale electricity generation, EIA reports. The bulk of that came from natural gas, at 43.1%. But renewables are growing quickly, accounting for 21.4% last year.

Renewable energy has a big advantage over fossil fuels. Namely, that the burning of fossil fuels for energy is the biggest single driver of climate change.

A working group of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said in 2022 that holding global warming under 2 degrees Celsius will require “substantial energy system changes over the next 30 years. This includes reduced fossil fuel consumption, increased production from low- and zero-carbon energy sources, and increased use of electricity and alternative energy carriers.”

But renewable energy, particularly solar power, has a distinct disadvantage: The sun and the wind don’t follow the commands of US grid operators. When the sun isn’t out and the wind isn’t blowing, they’re no help.

Solar panels generate a ton of energy when the sun is out, but none at night, and those don’t correlate with when people are using energy. You can solve this by storing that energy when it’s abundant and deploying it when it’s needed — the charging and discharging of a battery, but on a massive scale. These big batteries were a big help in getting California through a heat wave in July. A lot of small ones connected by a VPP can do the same thing.

When your home is the power plant

Electricity is a valuable commodity in Hawaii, more than in any other state. In 2022, a kilowatt-hour of electricity cost 43 cents. The national average was 15 cents. No other state was over 30 cents.

A rising share of the state’s energy comes from renewable energy sources — wind and solar — and those can be intermittent. Wind energy accounted for 6% of Hawaii’s total energy generation in 2023, but if the wind is blowing more than the grid needs at that moment, those extra kilowatt-hours could be wasted.

One solution comes from a VPP operated by the third-party aggregator Swell Energy, which works with Hawaiian Electric to manage 80 megawatts of home battery capacity across three islands.

“That’s the size of a gas peaker plant,” says Sarah Delisle, Swell Energy’s vice president of government affairs and communications.

These are ordinary homeowners with batteries, and they’re doing a range of things to support the grid. Delisle says the batteries Swell manages in Hawaii do three things: They can soak up energy that would be wasted, they can discharge batteries to meet peak demand, and they can quickly respond to help the utility balance the frequency of distribution.

“Between those three grid services, which all have different price structures, customers are seeing negative bills in Hawaii,” Delisle says.

The program also pays customers for participating with an upfront payment to help them purchase the Powerwall. That can be $10,000 or more, Delisle said.

These customers don’t control those Powerwall batteries in their homes, but they can set limits on how much power Swell can manage. The standard is that Swell won’t take the last 20%, leaving the customer some power for an outage, but customers can pick a higher number.

In Vermont, Green Mountain Power’s programs manage more than 3,000 batteries. And there are several ways you can join.

You can buy a battery, own it completely and connect it to the VPP. You can lease a battery from GMP. Or you can buy a house from O’Brien Brothers that has batteries included. GMP customers who lease for 10 years pay just $55 a month for two Powerwalls, or one payment of $5,500. At Hillside, the homebuyers who move into a single-family home will pay $85 a month for the “resiliency package,” which includes the trio of Powerwalls and the 8kW solar panel system.

The programs are designed to support the stability of the grid — saving money for everyone, Carlson says. “When we design any of our innovative programs, it benefits the participating customer and then it also benefits all of the nonparticipating customers as well.”

But that’s just the supply side of the equation. There’s also demand.

We’re using more electricity, and in different ways

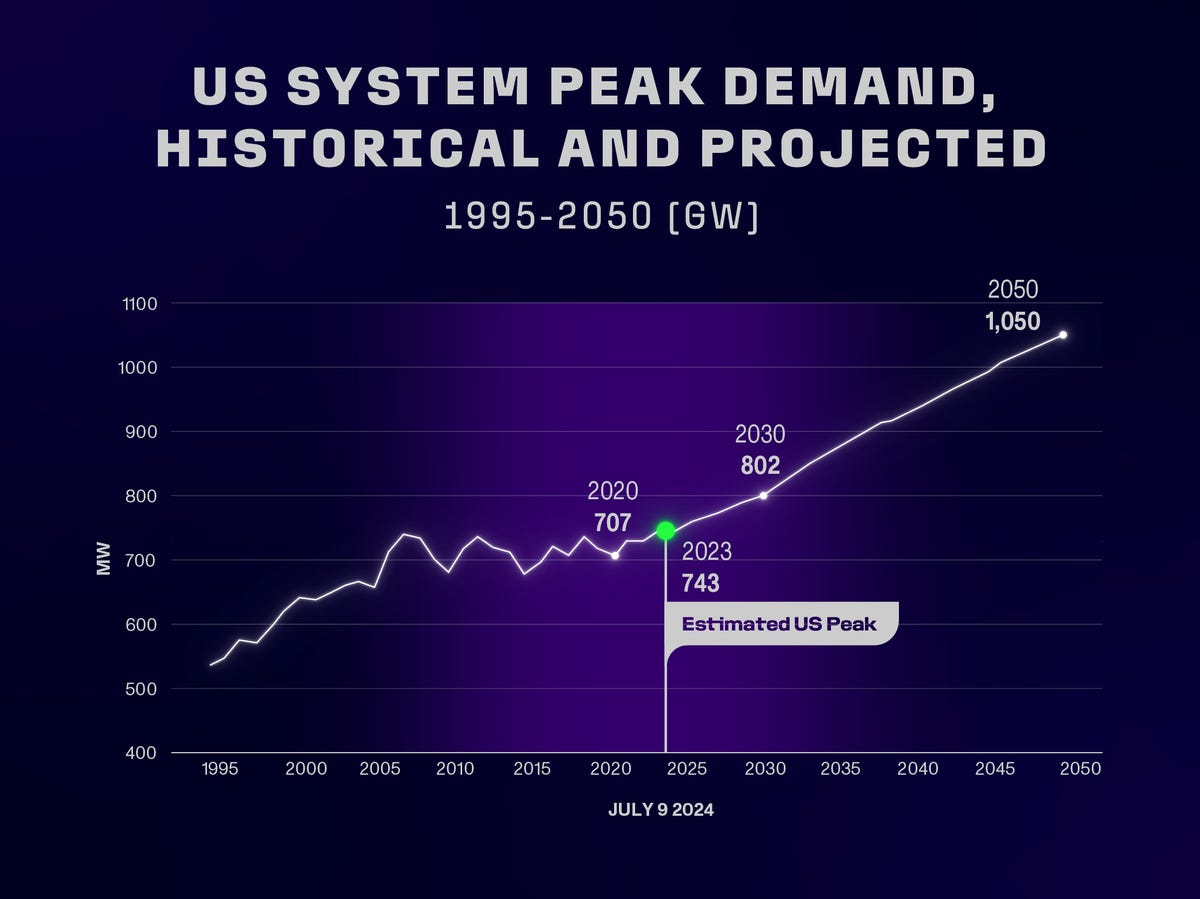

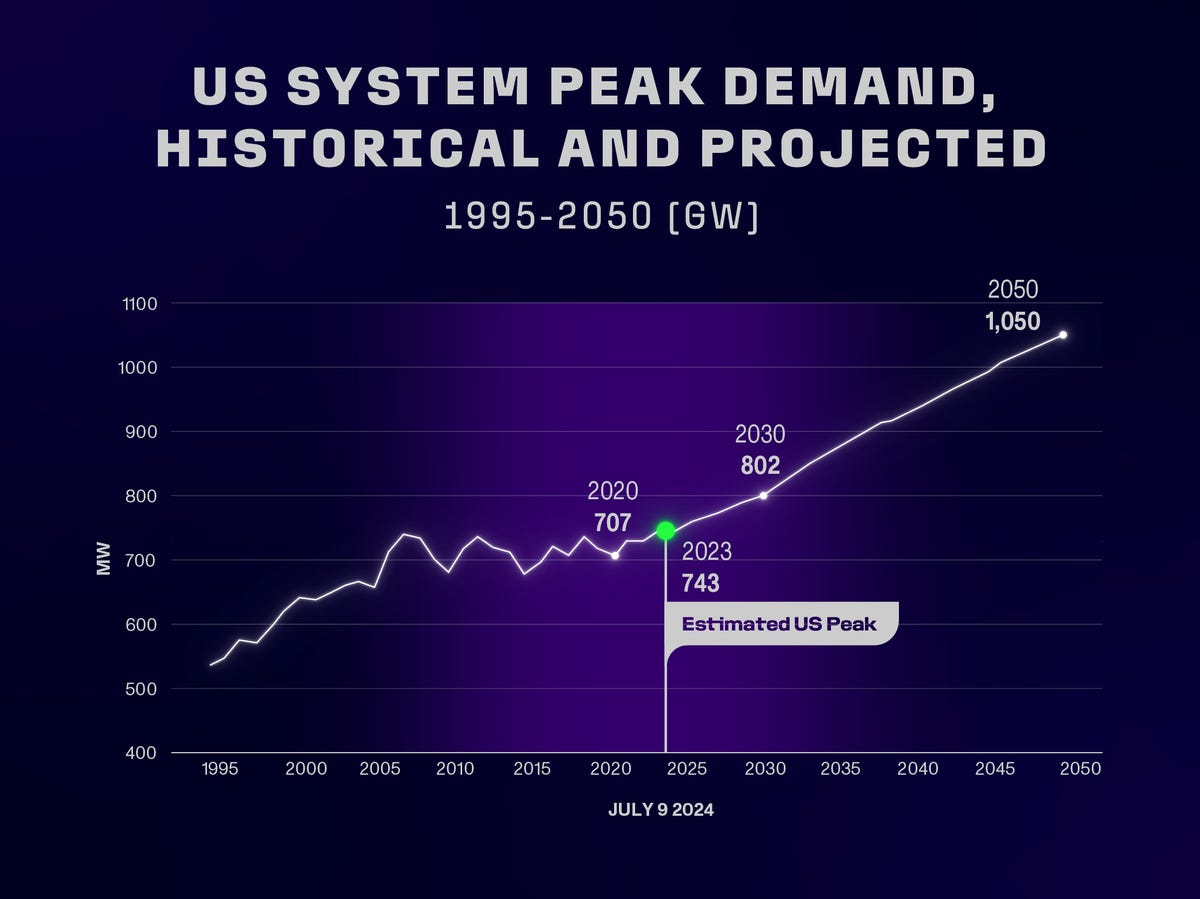

Despite an increasingly virtual society, US electricity demand held steady for decades because of improvements in efficiency. That’s changing. “Right now, we’re looking at demand that’s starting to grow again,” says Tom Wilson, principal technical executive at the Electric Power Research Institute.

Data centers are a big driver of that growth, Wilson says, thanks not only to the growth of the internet but to demand from cryptocurrency miners and artificial intelligence, as a recent report from EPRI found. The report estimated data centers’ electricity use would rise from 4% of US electricity generation today to between 4.6% and 9.1% by 2030.

“All of this adds up to a more robust economy, but it’s taking a lot of electricity, and it’s outstripping energy efficiency gains,” says Jen Downing, senior adviser for the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office.

Data from the US Department of Energy show how US electrical demand is expected to rise in the coming decades.

At the same time, we’ve seen remarkable improvements in the energy efficiency of products, particularly when you think about what you use around your home. The LED light bulbs in most of your light fixtures today use maybe one-tenth the amount of electricity that your old incandescent bulbs used a decade or two ago. The refrigerator in your kitchen is likely more efficient than those of two decades ago, by a sizable margin.

These two factors — more people and devices calling for electricity while using less, on average — have largely balanced each other out over the past two decades. Total US electricity demand has been essentially flat.

Demand is now rising again, thanks in large part to electrification. Moving from fossil fuels to electricity is good news for the reduction of carbon emissions, but it means the demand for electric power is rising faster than efficiency improvements are reducing it.

Our grid is built big enough to handle peak demand — the hottest day of the year, when everyone’s got their air conditioners running. Right now, it works pretty well. Power outages, for much of the country, are fairly rare.

But as demand increases, if we don’t do anything differently, the system will struggle. When there isn’t enough transmission infrastructure to get electricity from the generator to your home, outages get more common and last longer. And it’s really expensive to build all of that new infrastructure. Not billions or hundreds of billions of dollars but trillions of dollars, potentially.

But there is a cheaper option.

“The alternative to building up our supply infrastructure as much as we can is to smooth out those peaks in demand, and do it in such a way that it doesn’t inconvenience the consumer,” Downing says.

That’s what a virtual power plant is for.

Shaving peaks and saving power

When a peak event happens, Green Mountain Power’s Murray-Clasen has more than just a fleet of home batteries. She has a whole brigade of EV chargers.

If you’re enrolled in GMP’s EV charging program and the utility decides to call an event for the next day, you’ll get a notification that your EV charger may be turned off for a couple of hours.

EV chargers play a big role in a lot of virtual power plants, mostly on the demand side, by reducing load on the grid when it’s too high. But your car’s charger isn’t the only thing a VPP can use to slash the load on the grid during a peak.

An electric vehicle charger, like this one in the model home at Hillside at O’Brien Farm, can be connected to a virtual power plant and play a role in slashing energy demand during peaks.

Water heaters: a hidden grid superhero

You probably don’t think about your water heater until it stops working and you’re suddenly freezing in the shower.

The folks who operate VPPs think about them a lot more often, because they’re powerful tools. Water heaters use energy, yes, but the timing of when that energy is used doesn’t matter all that much. You can turn it off for a few hours and the homeowner will never notice.

“You would opt into the program and basically agree that after you take a shower, you don’t have to immediately heat that water back up in your water heater,” the DOE’s Downing says. “That can help smooth demand on the grid.”

You don’t need to turn the thing off forever, just for a few hours until the load drops. And because the timing is that short, it’s entirely possible you’ll never notice.

Smart thermostats: What’s a few degrees?

Then there are smart thermostats. The consumer’s sacrifice here is clear: What if everybody turns their temperature up a few degrees? Maybe 78 degrees Fahrenheit is still comfortable and uses less power than having it at 75.

That change might have a minimal impact on your well-being, Wilson says, but from the utility’s side, it’s possible that “being able to shave just a degree off of 100,000 thermostats would help you ride through.”

The benefit of one of these programs has been huge for Melissa Bryson, a customer of Renew Home’s VPP for more than five years. Through a program connected to her Nest Thermostat, Bryson gets points when Renew Home changes the temperature on her thermostat to conserve energy. And where Bryson lives in Bakersfield, California, she gets a lot of opportunities on 100-plus-degree summer days. Those points can be turned into bill credits or gift cards.

Some summers, Bryson says she’s made as much as $400 just by reducing her energy use, but it’s about more than just the financial savings. “If I get an alert that the grid is stressed, I can help reduce my energy to prevent a blackout for people that can’t have their power out,” Bryson says.

Not every VPP uses thermostats. Green Mountain Power doesn’t plan to include them. “We want to make this energy transition easy and seamless for customers,” Carlson says. “There’s no sacrifice here. You can live your life, you can have your power, you can stay cool when there’s a heat wave.”

Why your electricity use matters

The grid is a collective problem, which requires a collective solution, but a massive infrastructure buildout will hit all of us right in the power bill.

Instead, getting a lot of people like Bryson to do a lot of little things as needed can be cheaper than building tons of new natural gas peaker plants or transmission lines. The Department of Energy estimates a VPP can have a similar effect at 60% less cost than a gas peaker plant and 40% less cost than a grid-scale battery.

The problem stems from the timing of electricity use. Demand peaks in the evening, when everyone gets home from work and turns everything on. During the middle of the day, when most folks are away at work or school, residential power demand slumps. Plot this on a line graph and it starts to look, to energy nerds at least, like a duck. The tail is in the morning, the back is the low range through the middle of the day, and the head and beak come at that big evening peak.

On a particularly hot summer day, the duck’s head likely hits its peak at a time when electricity demand outpaces supply on the grid. It’s still hot but getting dark, so solar panels are fading.

To balance it out, you have two choices: add generation or reduce the load. A VPP can do both.

Demand reduction in action

July 4 brought more than fireworks and parades to Portland, Oregon. It brought a heat wave. The high temperature was 92 degrees at the airport that day. It hit 99 the next two days. On July 7, temperatures hit 100. The power company, Portland General Electric, sprung into action.

PGE has a couple of demand programs around thermostats. One is automated: Customers who sign up get a notification in advance, but when the peak comes the smart thermostat is controlled by PGE. The utility turned home temperatures down in the early afternoon hours before the peak, creating a buffer for what came later. When the peak came, PGE turned those temperatures up, making it a little warmer. The other program is more hands-on. It does the same thing, but customers have to change the thermostat themselves.

Both are voluntary, says John Farmer, senior communications consultant for PGE. Customers can choose to keep it cooler if they want. “If tomorrow at 5 p.m. you’re hosting a birthday party for your kid, and you don’t want 17 kids in your house sweating, you don’t have to participate in that event,” he says.

But plenty of folks did participate when PGE called grid events for July 8 and 9, when temperatures hit 102 and 104 degrees, respectively. On July 8, these efforts and others taken by PGE customers shaved demand by 109 megawatts. The next day, they shaved 100MW.

The previous few days of high temperatures had challenged the electric infrastructure. Farmer compares it to driving a car at 100 miles per hour through the Mojave Desert in 110-degree heat: If you push the machine that hard for that long in that heat, something will break.

Beyond grid reliability, there’s the cost savings of the utility avoiding purchasing electricity at its most expensive. There’s also the fact that customers, who are paid to participate in these programs, are actively supporting the system.

“For people to see and understand how it works, the benefits and why we do it and the fact that we’re going to have to be doing this a little more than we’re used to, there’s also that we’re trying to help folks understand,” Farmer says. “This is not going to be a once-a-year thing.”

Energy control applications and tools, like the SPAN app shown here, can help people cut their power demand and take more of a hands-on approach to their energy use.

Can VPPs save the grid?

The grid’s challenges are legion, but can software — and a lot of small batteries, EV chargers, thermostats and water heaters — actually solve them?

“That is still early on in the stages, trying to figure out exactly what a virtual power plant is and what it can provide,” says Howard Gugel, vice president of regulatory oversight at the North American Electrical Reliability Corporation. “It would be another tool that grid operators could use to try to keep that balance between load and generation.”

Still, the full value of VPPs has yet to be seen. Demand response has been around for decades, in the form of utility-run programs that could shut off pool pumps or change thermostats. But they’ve gotten more high-tech, more popular and more nimble.

VPPs may also help the system even if massive investments in transmission and distribution are still needed, by making those needs smaller and less urgent.

“Sometimes the value is not just in total savings, but it’s in providing a bridge to when you can actually build out the system cost-effectively,” Wilson says.

There are some concerns. One is the fact that these programs can be operated directly from the internet, making them vulnerable to cyberattacks, Gugel says.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle for VPPs is a matter of adoption. Some utilities are seeing the advantage, but in some places it will require utility regulators to nudge the utility companies themselves, Downing says. “It’s really just a matter of utilities creating these programs, enrolling these customers, and that hinges a lot on utility regulation and how state-by-state utility regulators are asking utilities, ‘hey, we have this cheaper alternative to serve this rising demand,'” she says.

Utility companies will have to think in different ways, Farmer adds. “You’ll see utilities become this energy services platform for the community.”

How to sign up for a VPP

VPPs help the grid, but they can also help you — if you can find one.

Here are some ways to see if you can get into one:

- Ask your utility: Your power company may have these programs listed on their websites. Or you can call customer service. They might go by different names: a thermostat program, a demand response program, a demand flexibility program.

- Check with your state or city: Your city, especially if it operates a municipal power company, may have a program. Or your state’s public utilities commission or other energy office may have a list.

- Have your smart thermostat look: Some smart thermostats have a function that takes your location and tries to identify available programs. This can make enrollment particularly easy. Other smart devices may have similar features.

- See if you’re on the list: VPPs are a hot topic in the energy industry, and they’ve been the subject of different reports. You can browse the Energy Department’s VPP Liftoff report, or RMI’s more recent Virtual Power Plant Flipbook.

And keep an eye on those newsletters your electric utility probably sends out once a month or so. Maybe they’re starting a program soon, and you can get in on the ground floor.

A new home: batteries included

Heat pump condensers on the outside of the Hillside development’s model home in South Burlington, Vermont. The homes in this development come with heat pumps and heat pump water heaters rather than appliances powered by natural gas.

If you moved to South Burlington, Vermont, you could buy a house ready-built to be in a VPP.

The Hillside development sits on what once was a working dairy farm owned by the original O’Brien Brothers. When the company started a homebuilding division in 2016, it built its first subdivision on some of the land. It was your typical suburban neighborhood, with gas pipelines underneath and nothing all that special about the energy infrastructure, except for a strong encouragement toward energy efficiency.

When it came time for Hillside Phase 2, that changed, says Evan Langfeldt, CEO of O’Brien Brothers. The developer went to Green Mountain Power and asked if it would be possible to build an all-electric community.

GMP said the builder could definitely do electric heating, cooking, cooling and EV charging, but a bigger plan could make the neighborhood totally resilient. So the utility brought in the batteries and the VPP components. O’Brien Brothers scored a unique selling point for its new homes and hit its goal of energy efficiency and electrification. Green Mountain Power — and the broader grid — got a big boost.

On a really high energy use day, this neighborhood could essentially be disconnected from the rest of the system — not creating a drain on the grid, operating on its own battery power, Carlson says. “We can treat this like it doesn’t even exist as an energy load on the system,” she says. “Or we can take this energy and put it back on the grid.”

This community’s energy infrastructure will support the grid for the towns and cities that surround it, Carlson says. It can be a net positive for the power company.

The development includes a mix of home types and sizes, from cottages priced in the $600,000 range to 2,500-square-foot homes priced in the $800,000 range. Zillow puts the average home value in South Burlington around $500,000. Langfeldt pointed to the cost of operating these homes, with their top-of-the-line insulation and energy efficiency package, saying the goal was to make sure they were priced competitively.

“While we may be kind of on the bleeding edge right now, I think in five, six, seven years this is going to become more and more the standard,” Langfeldt says. “The homes that are being built conventionally right now are going to be dinosaurs in 10 years.”

So far, at least, the developer is as happy with the results as the power company is.

“Maybe we have the benefit here in Vermont that people may be more leaning toward this, but who doesn’t lean toward energy savings and hedging against the future volatility of energy markets?” Langfeldt says. “It doesn’t matter where you are in the country. It doesn’t matter if you’re a conservative or a liberal. At the end of the day, it’s just how much money you’re saving and what you want for the future.”

Visual Designer | Zooey Liao

Senior Motion Designer | Jeffrey Hazelwood

Creative Director | Viva Tung

Video | Andy Altman, Chris Pavey, Adam Breeden

Project Manager | Danielle Ramirez

Director of Content | Jonathan Skillings

Editor | Katie Collins