The History of Black Baseball Players, On Full Display

Octavius Catto’s impact was largely unknown here at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, amid the sport’s legendary exploits like Joe DiMaggio’s streak of 56 consecutive hits, Ted Williams’ .406 batting average and Hank Aaron’s 715th home run, breaking Babe Ruth’s record.

Catborn a free black man, he switched to baseball in the shadow of the Civil War. He was a founder of Philadelphia’s all-black Pythian Base Ball Club, which also included Frederick Douglass’ son Charles. (They lost their first game 70-15, but improved quickly.) The Pythians applied to Pennsylvania’s association for amateur baseball and the National Association of Base Ball Players, but were denied.

The story of Catto, who was also a civil rights activist before his assassination in 1871, is one of many the museum presents in its new exhibit, “The Souls of the Game: Voices of Black Baseball.”

“It’s been documented that we’ve been playing baseball since the days of slavery,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo., and a member of the exhibit’s advisory committee. “Baseball has always been an important part of the African-American experience in this country. It’s just that it hasn’t been documented in the pages of American history books.”

The exhibition opens at a time when the percentage of American-born black players in Major League Baseball is at a historic low. About 40 percent of players in Major League Baseball last season were players of color, according to a report from the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, but only about 6 percent identified as black or African American, the lowest since tracking began in 1991. The 2022 World Series, between the Philadelphia Phillies and Houston Astros, featured no American-born black players for the first time in 72 years.

“It continues the conversation, which is great,” three-time All-Star Curtis Granderson said of the exhibit. “And that’s what you want. You want the conversation to move from one generation to the next.”

In recent years, baseball has attempted to correct previous omissions and mistakes regarding its history. Nothing is more important than the recent integration of statistics from several Negro leagues into the official Major League Baseball statistics, with Josh Gibson, for example, replacing Ty Cobb for the highest batting average of all time. The Hall of Fame, which is not funded by Major League Baseball, also recognized in recent years that the legacy of shrines like Kenesaw Mountain Landis and Cap Anson included preserving the color barrier that lasted until 1947.

One player the Hall of Fame recruited to the recent advisory committee was Dave Stewart, a standout starting pitcher and World Series Most Valuable Player with the Oakland A’s, who discussed the full spectrum of his experiences to help inform the exhibit. Early in his career, he found himself isolated as the only black player on a team while driving through small minor league towns. Once, he said, a racist tried to run him over in a parking lot in Mississippi. But eventually he was able to meet heroes from previous generations, like Bob Gibson, Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe, and find camaraderie.

“We talked about those experiences and what it felt like to be in that situation and how I was treated or how we were treated at the time,” Stewart said. “We talked about the style of play. You look at guys like Rickey Henderson and Reggie Jackson, and the style and the type of play and what they did. Were they more acceptable or less acceptable because it was Rickey Henderson who did it versus if Cal Ripken had done something like that?”

During the opening of the exhibition, an exhibition match was played with more than two dozen former black top players, such as Granderson, Matt Kemp and Prince Fielder.

“The reason I said yes was to get a chance to be around all those guys again,” said Granderson, who played in the majors from 2004 to 2019. “It’s the first time I’ve ever been around that many black ballplayers, played against, watched growing up.”

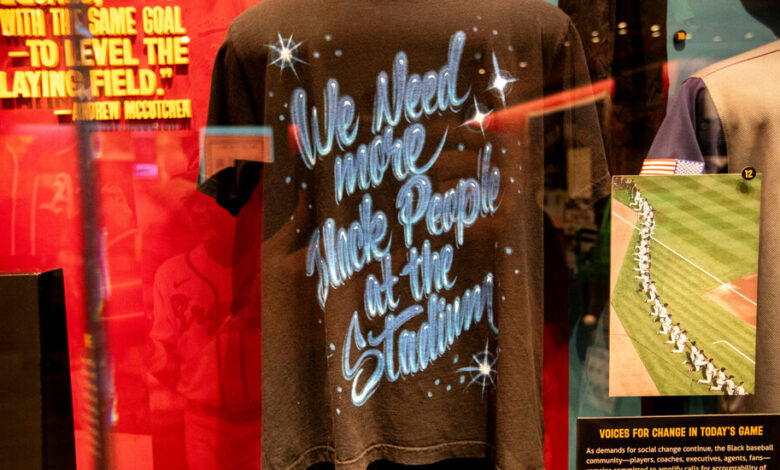

It was a reminder that even recently, black representation on the big league diamonds was more common. Among the items in the new modern era exhibit section is a T-shirt Mookie Betts wore to the 2022 All-Star game that read “We need more Black people at the stadium.”

TOM SHIEBER, THE SENIOR CURATOR OF THE HALL OF FAME, read from “De Witt’s Base-Ball Guide of 1868” during a recent tour of the exhibit. The document noted that the rejection of Octavius Catto’s team, the Pythians, from the National Association of Base Ball Players was based on the reasoning that “if colored clubs were admitted, there would in all likelihood be some division of feeling, while by excluding them no one could be harmed.”

“It’s like, ‘What?’” Shieber asked. “It’s so weird to connect the dots like that, but it is. One thing we’re saying here is that the color line isn’t just drawn at that one moment. It gets heavier and bolder and bolder and stronger as everything else happens.

The new exhibit explores Jackie Robinson’s life beyond that barrier, along with other, lesser-known hurdles. Among the items on display is the championship ring a 19-year-old Hank Aaron received when he integrated the South Atlantic League in 1953.

Robinson’s story is universally celebrated as the story of triumph and salvation that it is. But reintegration, as Shieber likes to call it, coincided with the collapse of the Negro Leagues. The exhibition does not shy away from examining these consequences.

“It’s definitely a bittersweet story,” Kendrick said. “Those owners and the older players in the Negro Leagues basically took one for the team. It reminds us that there is always a price for what is considered progress. And the black economy paid a high price for this progress.”

After the reintegration, Major League Baseball executives instituted an unwritten quota system that limited the number of black players on rosters, Shieber said.

“This resulted in skewed transactions,” he added. “That’s not just a one-to-one transaction. That’s a, ‘We have enough black players trading.’

Toward the end of the exhibit, Shieber pointed out the locker once used by Willie Mays, which Barry Bonds took over while playing for the San Francisco Giants.

One of Stewart’s fondest early memories was meeting Mays, his favorite player, as a five-year-old. But Stewart also looked up to Gibson, Aaron, Frank Robinson and a host of other black stars.

Today, he said, kids are likely to imitate Betts. He was hard-pressed to name another current American-born black star.

Beneath the surface, the numbers are improving. The competition has established various programs to encourage, identify and nurture young black players. A increasing number of Black players have been among the top draft picks in recent years — 12 of the first 100 three years ago, 13 of the top 100 in 2022 and 10 of the top 50 in last year’s draft.

“We’re going to have to be patient, but as a society we’re not very patient,” Kendrick said. “This trend didn’t happen overnight. The solution won’t happen overnight.”

Telling stories like Catto’s, from 150 years ago, will help these efforts, Kendrick believes. “It will be,” he said, “an awakening.”