The number of NHS cancer patients facing waiting times of more than 100 treatments to start treatment has skyrocketed since the pandemic… with people over 60 most likely to be affected by delays

The number of cancer patients eligible through the NHS facing agonising waits of more than 100 days before treatment can begin has soared over the past five years, a damning report has found.

Nearly one in eight people with an emergency referral in England (around 20,000) experienced a delay of more than three and a half months in 2022.

This is an increase from about one in 25 in 2017, meaning that this number has tripled compared to the pre-pandemic period.

Data shows that early-stage cancer, when the disease is still easily treatable, can increase survival rates by up to eight times.

Experts blame the increase on a shortage of staff, beds and hospital equipment, further increasing the pressure on health care.

Nearly one in eight with an emergency referral – around 20,000 – were delayed for more than three and a half months in 2022. This is up from just four per cent in 2017. Pictured is Amy Gray with her mother Jayne who died six months after her bladder cancer diagnosis.

Detecting cancer early, when it is most treatable, can increase survival rates by up to eight times, data shows. Pictured: Amy Gray with mum Jayne and dad Steve

The analysis also found that people between the ages of 60 and 69 were most likely to experience long waiting times.

If urgent action is not taken to tackle this rise, the NHS will be ‘unprepared for the situation’, researchers have warned.

Dr John Butler, a surgeon specialising in ovarian cancer and clinical advisor to Cancer Research UK, which conducted the research, said: ‘Every day, oncology surgeons across the UK see patients who have waited longer than necessary for diagnosis and treatment.

‘The NHS is treating more patients than ever before, which is fantastic, but we want to do more – and capacity is what’s holding us back.

‘Our health care system is limited in diagnosing and treating cancer patients. The resources and staff are simply not expanded to meet the demand.

“This capacity problem — a shortage of beds, equipment or staff — started before the pandemic and it could get worse.

‘The UK’s ageing and growing population could see around half a million new cancer cases diagnosed each year by 2040.

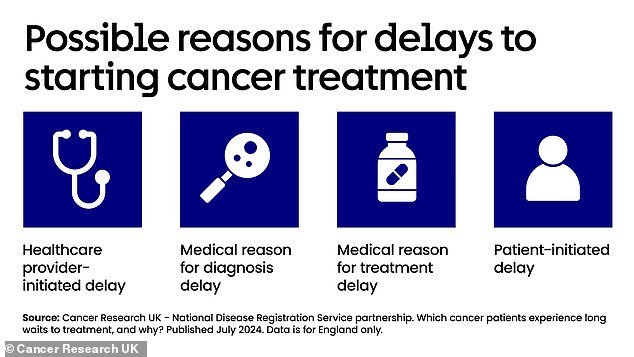

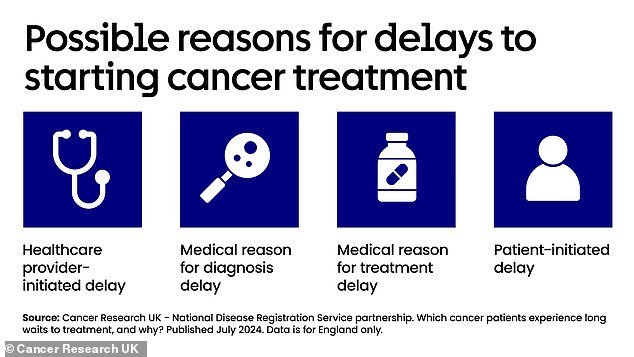

Under NHS policy, the health service must review all waiting times of more than 104 days to confirm whether delays were preventable. When assessing the reasons for these delays, Cancer Research UK and the National Disease Registration Service found that almost half in 2022 were attributed to a lack of staff or equipment

Experts blamed the rise on a lack of staff, beds and hospital equipment, putting additional pressure on the health service. Unless urgent plans are made to deal with this rise, the NHS will be ‘unprepared to cope’, they also warned.

“If we don’t plan for this soon, the NHS won’t be prepared for this.”

In England, more than 320,000 people, or 900 a day, are diagnosed with cancer each year. The most common types are prostate, breast, bowel and lung cancer.

In 2020, cancer care for some patients effectively ground to a halt as the pandemic first reached the UK, with appointments cancelled and diagnostic scans postponed due to the government’s commitment to protecting the NHS.

Experts estimate that 40,000 cancer cases went undetected in the first year of the pandemic alone.

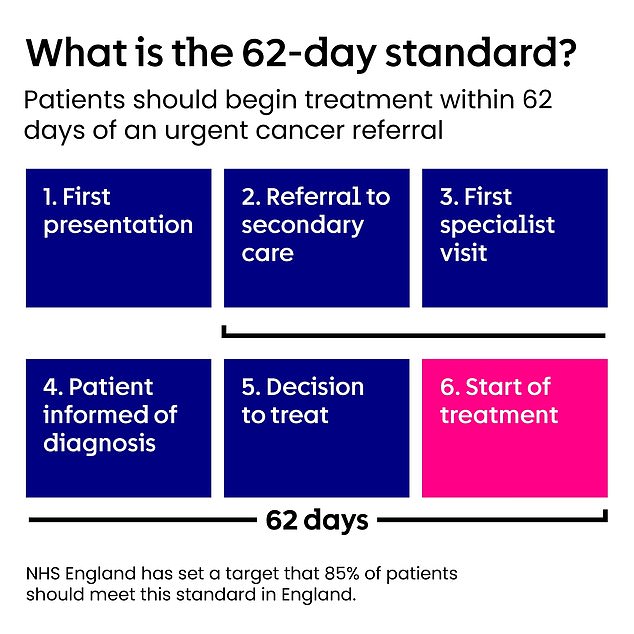

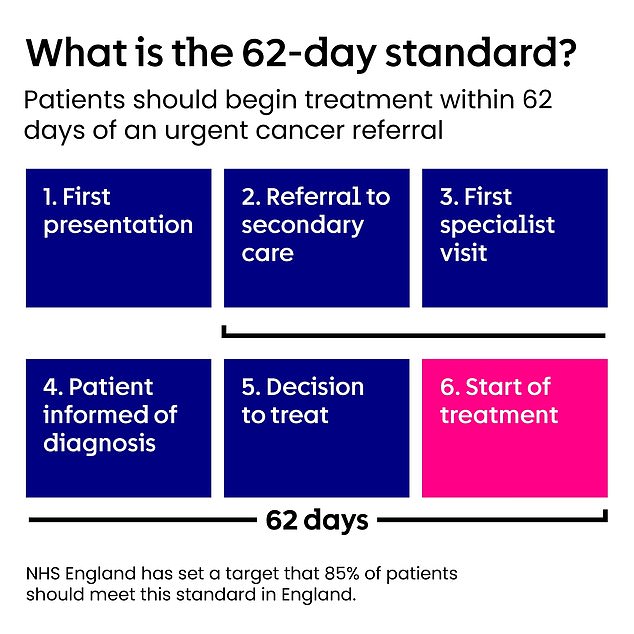

NHS cancer care also repeatedly fails to meet its targets.

Figures released earlier this month showed that NHS England has met one of its three cancer diagnosis targets for the first time since records began.

Of the 273,810 emergency referrals for cancer made by GPs in May, 76.4 percent were diagnosed or ruled out within 28 days.

The goal is 75 percent.

Less than two-thirds (65.8 percent) of patients started their first cancer treatment within two months of an emergency referral.

According to NHS guidelines, 85 per cent of cancer patients should be treated within this time frame.

Under NHS policy, the health service must review all waiting times of more than 104 days to confirm whether delays could have been avoided.

In an investigation into the reasons for these delays, Cancer Research UK and the National Disease Registration Service concluded that almost half of the delays in 2022 were due to a lack of staff or equipment.

Medical reasons for delays in diagnosis, such as patients needing multiple or complex tests or being temporarily unwell for the required tests, accounted for about a quarter of the long wait times.

Meanwhile, patient-inflicted delays, such as patients canceling or rescheduling appointments, accounted for six percent of long wait times.

More than half of the long waiting times were caused by lower gastrointestinal cancers, such as colon and anal cancer, and by urological cancers, such as prostate and kidney cancer.

This is probably due to a shortage of specific diagnostic equipment and the complexity of the required decision-making and treatment planning.

Patients with breast and skin cancer were least affected by long waiting times, but numbers still increased.

The charity says more research is urgently needed to fully understand why long waiting times have increased so substantially.

Michelle Mitchell, chief executive of Cancer Research UK, said: ‘NHS staff are doing their best, but these figures are worrying.

‘It is positive that more patients than ever are being treated and that people know more quickly whether they have cancer or not.

‘Yet too many patients wait too long to start cancer treatment. This report highlights how far we still have to go.

‘A long-term strategy is needed to deliver on the promise of reducing waiting times for cancer patients by providing our NHS with the equipment and staff we desperately need to diagnose and treat patients in time.’

Leading oncologist and chairman of Radiotherapy UK, Professor Pat Price, told MailOnline: ‘The near-tripling of three-month delays in cancer treatments is nothing short of a tragedy.

‘Every four weeks of delay in cancer treatment can increase the risk of death by 10 percent.

‘These statistics are representative of people and provide further evidence of the deadly impact of cancer on Labour.

‘Differences based on age and location are further exacerbated by the fact that we do not have a dedicated national cancer plan in this country.’