The rise and rise of the Premier League’s border coaches

Follow today’s live coverage of Atalanta vs Arsenal in the Champions League

When Oliver Glasner was growing up in the small Austrian town of Riedau, the Bavarian border was just 32 km (20 miles) to the north. That meant that three of the five channels he could watch on television were German.

“I could see a bit more than the average Austrian,” the 50-year-old Crystal Palace manager said The Athletics ahead of his team’s draw with Leicester City last weekend.

Glasner admitted he didn’t realise it at the time, but his geographical place in the world opened his eyes and therefore his mind to wider possibilities. He was also exposed to wider European football in a way that many other Austrians weren’t: the country’s national teams weren’t as successful as neighbouring Germany’s, and therefore there were fewer games on TV to watch. It certainly broadened his understanding of the game he came to love. “I’ve always been crazy about football…” he concluded.

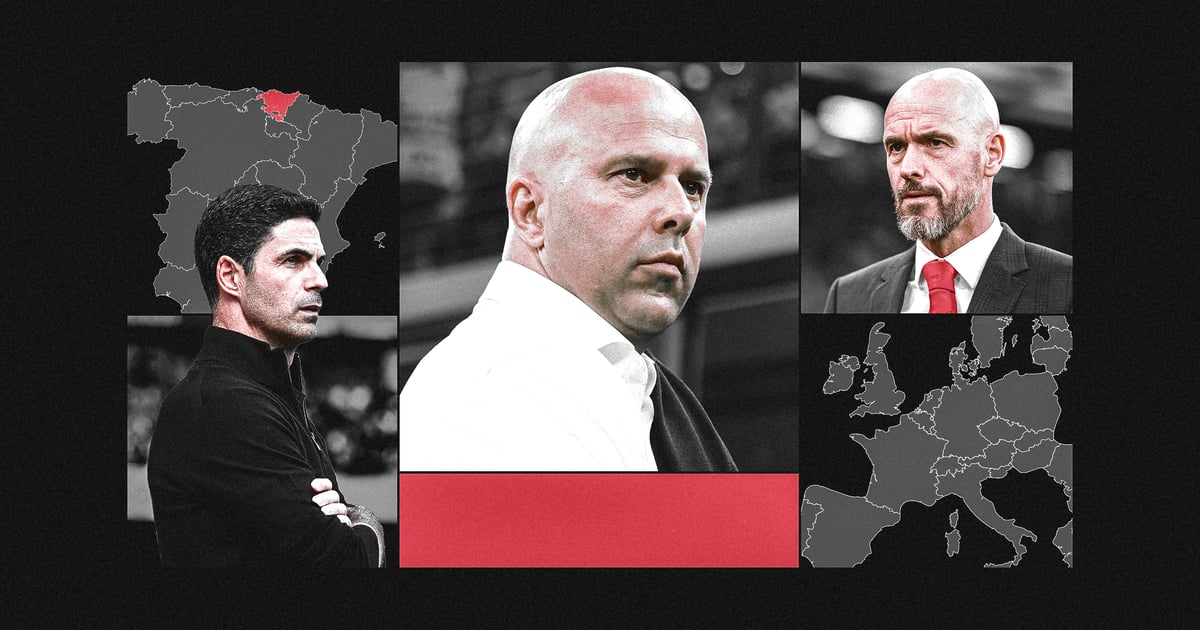

Glasner is no exception in this season’s Premier League: nine of the division’s 20 managers were born or raised within 30 miles of a national border. Erik ten Hag, Arne Slot, Unai Emery, Mikel Arteta, Andoni Iraola, Thomas Frank, Kieran McKenna and Julen Lopetegui complete the list.

Another, Pep Guardiola, comes from Catalonia, a region that has long sought autonomy from Spain, while yet another, Nuno Espirito Santo, hails from São Tomé and Príncipe, an island nation off the Atlantic coast of Africa that has been independent for less than 50 years.

It seems this is the season of the border manager, four of whom play each other this weekend.

At Selhurst Park, Palace play Glasner against a Manchester United team led by Ten Hag, who was born in Haaksbergen, the Netherlands, just 10km from Germany. At Anfield, Liverpool’s Slot (who grew up in Bergentheim, a city in the Netherlands 12km from Germany) plays against Bournemouth and Iraola, who hail from Usurbil, Spain, just 34km from France.

But is this just a geographical oddity, or a trend that says something about the characters of the managers of many of England’s top clubs?

Of the four Premier League managers this season who hail from the Basque Country, in northern Spain near the French border, Unai Emery is perhaps the ultimate border coach.

He grew up in the border town of Hondarribia, separated from France by the Bidasoa River, and his career is one to behold, having managed the most clubs in the most countries of any manager with connections across the border, with nine stints in Spain, Russia, France and England. By modern standards, especially at the highest level, this qualifies him as a travelling coach.

“I left my parents’ house at 24 – Hondarribia, San Sebastian, Real Sociedad – and opened myself up to the world of football: I carried my suitcase, faced many difficult moments and left my comfort zone,” Emery told the British newspaper The guard in 2022, shortly before he left again and swapped Villarreal for Aston Villa in his home country.

Emery played just five games for Real Sociedad, his boyhood club, and would spend the majority of his playing career in Spain’s second division. Perhaps his path was one of necessity: he had to earn a living, and he wanted to do it in football. But perhaps the travel involved in that process was made a little easier by the fact that, as a child, somewhere else was never that far away.

Although he watched planes fly over the Bidasoa estuary just west of San Sebastian, landing at Donostia airport (another reminder that there was a world waiting to be explored), the details of the geography certainly matter: Hondarribia fades into another Basque town called Irun just south of there, which then merges into Hendaye — also Basque, but in France. The area was one of the busiest border crossings between the two countries, and travelers could sometimes make the journey by train without showing their passports.

It is tempting to think that this made Emery more intellectually curious and easier to work with people from other cultures. However, psychologists suggest that this upbringing may have pushed him in the opposite direction, which could explain other aspects of his management.

Emery grew up in Spain, but within a long goal kick of France (Justin Tallis/AFP via Getty Images)

“Proximity to multiple cultures, including languages and different traditions, can help with adapting to new environments, resolving conflicts and being sensitive to differences,” says sports psychologist Marc Sagal, who has worked with several Premier League clubs. “Perhaps from a less obvious perspective, it could help to anchor and solidify one’s identity a little bit. In other words, there may be times when, because of so many other influences, there is a desire to protect and preserve one’s way of doing things.

“Border regions often have unique identities that are very separate from the countries to which they belong, which can lead to individuals clinging to their local culture. The desire to preserve one’s unique cultural heritage can manifest itself in football managers as an exceptionally strong attachment to a style of play, football philosophy or identity.

“The Basque identity is powerful and culturally different to that of Spain and France. It’s easy to see how this could result in a more insular approach, a desire to promote local talent or to stick to a specific tactical philosophy. From the outside, it seems that Emery is a little more rigid in applying his philosophy and Basque-influenced methodology than (San Sebastian-born Arsenal manager) Arteta, for example, who seems rather keen to create an environment that best suits the players. Both approaches can be very effective and both are probably influenced in part by geography and experience.”

Emery’s relationship with France would undoubtedly have been different from Ten Hag and Slot’s relationship with Germany. While Spain and France for Emery met in an urban expanse, with a clear border, for the two Dutchmen their experience of borderland was rural.

Drive around Haaksbergen and Bergentheim and you might not even realize that you’ve gone from the Netherlands to Germany and back again. Yet, as The Athletics When they visited both cities in May, they discovered that the residents of these Bible Belt cities felt very Dutch and only crossed the border to buy cheaper fuel for their cars.

Arne Slot grew up in the quiet town of Bergentheim (Simon Hughes/The Athletics)

Slot, however, is far from closed-minded. Dan Abrahams, a sports psychologist who worked with him for two seasons when he was manager of Rotterdam club Feyenoord before leaving for Liverpool this summer, describes his former colleague as The Athletics as “very open-minded” and a coach who is willing to “challenge existing views on Dutch football”.

Bergentheim is conservative, religious and austere, but Slot developed a more Burgundian lifestyle as he pursued a playing career that took him closer to the other side of the country, near the Belgian border, during a five-year stint at NAC Breda.

Abrahams refers to the “biopsychosocial model” first conceptualized by American psychiatrist George Engel in 1977, who suggested that in order to understand a person’s medical condition, biological factors should not be the only consideration, but also psychological and social ones. “What people experience is the product of complex interactions,” Abrahams says. “Our social environment is a major mediator of who we become.”

He identifies Slot as a “critical thinker.” The coach gave Abrahams permission to be honest with him, but he controlled and challenged what he had to say, pushing his boundaries. How much of this was due to his experiences in Bergentheim was difficult to gauge (his conversations with Slot did not concern his background), but ultimately Abrahams believes that living near another country with an identity as strong as his own must have had an effect. “Such proximity can make someone more inward-looking or outward-looking,” Abrahams concludes.

It seems obvious that the location of a place influences the industry and thus the employment that exists there.

Big companies are moving to big cities, but few of the current crop of Premier League managers grew up in a metropolitan environment. Only four of them grew up in large conurbations: Marco Silva of Fuham (Lisbon), Gary O’Neil of Wolves (London), Ange Postecoglou of Tottenham (Melbourne, after being born in Athens) and Fabian Hurzeler of Brighton (Munich, via Houston in the United States).

Large cities, though sometimes on the border, are not usually built near other countries, for the simple reason that rulers feared losing them to invasion. Outside of the no-man’s land on either side of a border, smaller settlements therefore tend to encourage handicraft, and as such have a requirement among the inhabitants for graft.

Neither Slot nor Ten Hag had manual labour in their blood. While Slot’s parents were teachers and lower-middle-class, the Ten Hags had a property empire and were certainly not short of money. Yet a strong work ethic was still fundamental to their ethos and influenced the way each manager operated.

Evidence of the Ten Hag ownership empire in Haaksbergen (Simon Hughes/The Athletics)

While the geography around Guardiola is different, he shares traits with obsessive figures like Ten Hag and Slot, if you listen to those who know him best.

Catalonia and the Basque Country are not poor regions, but their claims for independence are linked to their economies and the way people feel they should benefit from local resources.

Guardiola grew up in Santpedor, 70km north of Barcelona. According to writer and film director Dave Trueba, speaking to the BBC in 2018, what defines the Manchester City manager is his willingness to get his hands dirty rather than the alternative way of thinking that sometimes manifests itself in his football teams.

“When it comes to analysing or judging Guardiola, you have to keep in mind that beneath the elegant suit, the cashmere sweater and the tie, there is the son of a bricklayer,” Trueba said. “Inside those expensive Italian shoes is a heart in espadrilles.”

He has also achieved a great deal: Guardiola has coached in Catalonia, Germany and now in the north-west of England, and has become the most celebrated coach of his generation.

Like many of his peers, he has learned to look beyond his horizons and look at the world around him.

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: John Bradford)