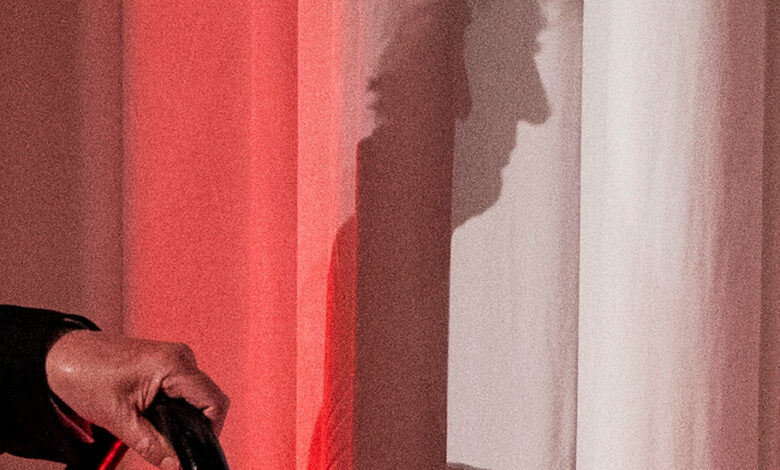

Trump will encounter a very different Middle East in his second term

Observers of President-elect Donald Trump have long known the folly of predicting his decisions. But when it comes to foreign relations, especially in the Middle East, there are some ways in which his second term will undoubtedly be different from his first.

The region has changed dramatically since Hamas’s October 7 attacks on Israel, which upset the balance of power and the priorities of its key players.

It’s impossible to say what’s coming. But my colleagues have reported extensively on everything that’s changed, and this seems like a good time to bring some of their findings together.

October 7 attacks

Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7, 2023 was one of those moments that divides history into ‘before’ and ‘after’. In the attack, Hamas massacred civilians in Israel and took others back to Gaza as hostages. As my colleague Steven Erlanger wrote just two weeks later, the attacks shattered long-standing assumptions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, ushering in a period of violent uncertainty.

During Trump’s first term and much of President Biden’s, Palestinian demands for statehood received little attention. Israel controlled the West Bank and held Gaza so tightly that it seemed as if the status quo would continue indefinitely.

But the Hamas attack and the wars and realignments that followed changed everything. The United States is once again deeply involved in the region, providing military support to Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon. And widespread anger over Israel’s behavior, which has killed tens of thousands of people and displaced more than a million, has brought renewed attention to the issue of Palestinian statehood.

As I have written in recent columns, if Israel and Iran fail to achieve a new balance of deterrence against each other, their conflict could intensify, potentially attracting other countries.

Saudi Arabia and Iran: from cold war to détente

For most of the 2010s, Saudi Arabia and Iran used proxy fighting to fight a cold war in the Middle East. Their rivalry was a kind of decoder for the region’s many civil wars and for sectarian tensions between Sunni and Shia Muslims: Iran supported Shia militant groups across the region, while Saudi Arabia sought influence through its own Sunni proxies.

That is starting to change. In March 2023, China reached an agreement restoring relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia. As my colleagues Farnaz Fassihi and Vivian Yee reported, countries agreed to reopen embassies; reviving an old security treaty; not attack each other, even through proxies; softens the rhetoric in the news media; and not interfere in each other’s internal affairs.

Many of these promises are currently more ambitious than realistic. “I would call it a cautious détente, a cautious opening, a cautious willingness to just work together to de-escalate,” said Anna Jacobs, a senior Persian Gulf analyst for the International Crisis Group.

The thaw in relationships was prominent this week, as my colleague Ismaeel Naar reported. Saudi and Iranian military leaders met in Tehran on Sunday. That same day, the Saudi Press Agency reportedthe president of Iran spoke directly by telephone to Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia and its de facto ruler.

That dialogue “sends a very strong message, especially with Trump’s re-election, that the region is very different from Trump’s first term,” Jacobs said. “The relationship between Saudi Arabia and Iran is very different now.”

A setback for an Israeli-Saudi pact

Before the October 7 attacks, Saudi Arabia and Israel appeared to be on the verge of an agreement to normalize their relations, which had the potential to reshape the Middle East. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel hoped that such an agreement would lead to the creation of a kind of NATO in the Middle East, creating closer security ties between Israel and the Gulf states and further isolating Iran and its allies.

Now things look very different. Israel’s wars in Gaza and Lebanon have made it untenable for Saudi Arabia and other countries to strike a deal with Israel unless they make significant concessions, possibly including a commitment to a Palestinian state – but Israeli opposition to a two-state solution is stronger now than it has been for decades.

Combined with the detente between Iran and Saudi Arabia, this raises the possibility of a new regional order in which Israel, rather than Iran, becomes more isolated.

Trump’s unpredictability Part II

During Trump’s first term, many argued that he was pursuing the “crazy strategy” in foreign affairs. That’s the idea that if your opponents think you’re unstable enough to follow through on a threat despite potentially disastrous consequences, they’re more likely to back down.

While there may be a strategic logic behind pursuing the crazy strategy against adversaries, erratic behavior toward friendly countries may cause these countries to withdraw and seek other alliances.

In 2019, a missile attack hit Saudi Arabia’s main oil installations in Abqaiq and Khurais. The US accused Iran of carrying out the attack, although the Houthi rebel group, an Iranian-backed militia in Yemen, claimed responsibility. Trump said there was “no rush” to respond because he did not want to draw the US into a war.

That response appears to have contributed to the Saudi decision to pursue a reset with Iran, according to a report of the International Crisis Group.

The second Trump administration may send more mixed signals. As my colleagues Lara Jakes and Adam Rasgon have written, Trump’s nominees for top diplomatic envoys to the Middle East have little foreign policy background but have demonstrated fervent support for Israel.

And while Trump has long taken a tough stance on Iran, Elon Musk, a close adviser to the president-elect, met with two Iranian officials this week to discuss ways to defuse tensions between Iran and the United States, it was reported my colleague Farnaz Fassihi.