Welcome to Las Vegas … the epicenter of college football chaos?

LAS VEGAS – From the shady corner at Rebel Fields, the view stretches clear from Mandalay Bay to the MGM Grand to the southeast tip of The Cosmopolitan. Only a few palm trees break it up. The sky is cloudless. Temperatures haven’t cracked 80 degrees yet. There’s a Zach Bryan tune on the speaker system as the nationally ranked UNLV football team lines up to stretch, just like it did the day before, at the same time, with the same backdrop.

It is a Wednesday. It’s pretty much the same as Tuesday. Except everyone knows the starting quarterback is not here.

“I expected a bigger turnout,” a support staffer says, passing by a small group of onlookers. “No. 1 trend in America!”

This is well past online-only upheaval, though, during the most tantalizing start in program history. The previous night, quarterback Matthew Sluka, who ran the undefeated Rebels’ kinetic offense to a first-ever appearance in a Top 25 poll, quit. He cited unfulfilled promises in the realm of name, image and likeness payments. He wished everyone continued success and then left the toaster in the bathtub.

By sunrise, there are denials and warring narratives. Coast-to-coast howling about the state of the sport. By the fifth period of practice, Sluka is wiped from the online roster. And it’s not even the first flashpoint of the week. Another round of conference realignment tug-of-war has forced UNLV to choose its future home, quickly. So, in sum, a long-forgettable program prepares for its first game as a ranked team, another step toward possibly redefining its future as a Cinderella in the 12-team College Football Playoff era, while university officials and powerbrokers navigate an existential dilemma and trip into the anarchic world of NIL.

That’s all.

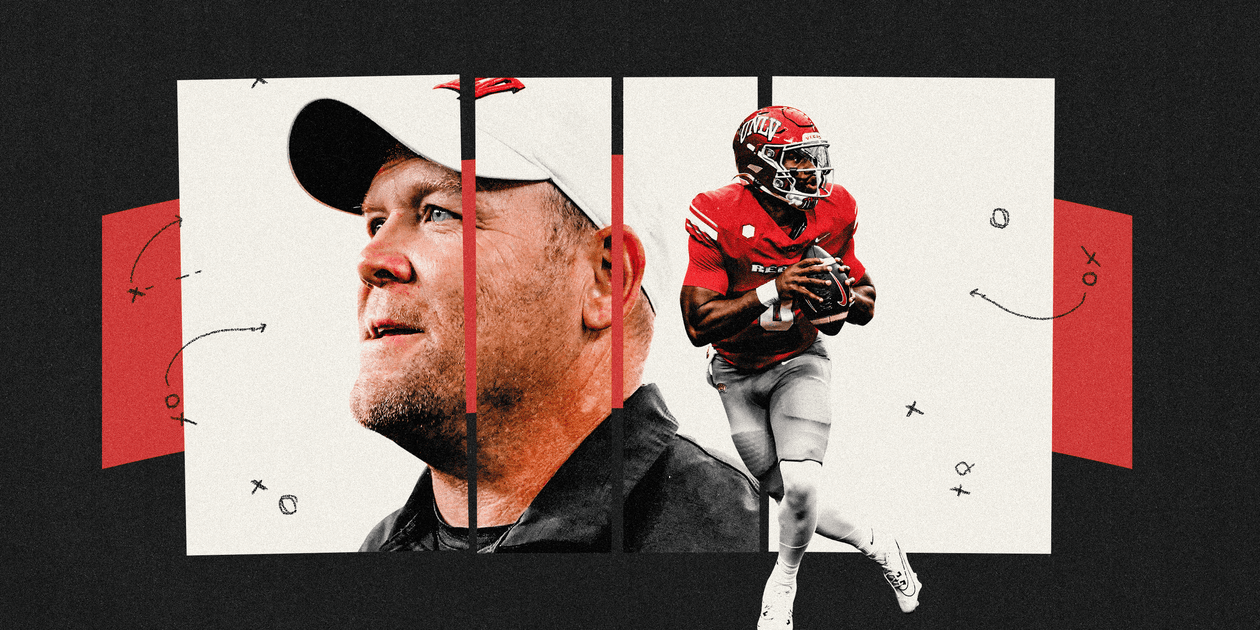

“Focus, focus, focus!” second-year Rebels coach Barry Odom barks after a brief post-stretch huddle. If only. Everything great and terrible about college athletics in 2024 has descended upon Las Vegas in the span of a few days. But then, that’s the way it is for a team aspiring to be what UNLV wants to be.

It’s going to be 104 degrees here by Saturday, too. No hiding from the heat.

In 47 seasons at the Division I level, UNLV football has won double-digit games once. This was the 11-2 campaign of 1984, with future NFL star Randall Cunningham under center … which the NCAA eventually vacated entirely due to the use of ineligible players. Before the current staff’s arrival, the program reached three bowl games, total. Before 2023, the Rebels had posted one winning season since the turn of the century. Moses spent less time wandering in the desert. “Growing up,” Nicco Fertitta says, “it was as if UNLV didn’t exist.”

The Vegas native, former player at powerhouse Bishop Gorman High and current Rebels safeties coach is sitting in the media room of the Fertitta Football Complex. It opened in 2019, cost $35 million to build and, yes, bears his family name. (A $10 million pledge from his father, a former UFC CEO, and his uncle kickstarted the project.) It features a 10,000-square-foot weight room, a 120-seat cafeteria, an academic center and a barber shop. It is not the biggest or most ostentatious facility in the country. It is nevertheless a crisp, modern, one-stop operations hub. It is very much a sign of life.

Though the front doors don’t completely work right. “We’re still trying to get it fixed,” Barry Odom says, setting his lunch of Diet Coke and Cheez-Its aside in an office with a sprawling vista of The Strip.

A nuisance more than a problem. For one thing, the current head coach was once on a recruiting trip in the area for Arkansas when he drove by the facility and deemed it too cool not to explore. He parked his rental car in the lot and found the janky entrance propped open. He walked in, encountered nobody and began a self-guided tour.

He’d probably be here now anyway, he thinks, steering the Rebels to nine wins in Year 1 and this auspicious start in Year 2, which includes victories at Houston and Kansas, their first win against Fresno State in seven years and debuts in both major national polls. It just didn’t hurt to see before he believed. “We can be in the conversation on a national scope every single year,” Odom says. “If you schedule correctly, non-conference-wise, and you’re able to win those games, then now there’s the opportunity for a seat at the big table.”

This is what any coach tells anyone who’ll listen. The trajectory of the last 17 months makes it sound credible, at least.

“The rapid growth we’ve had is pretty crazy, honestly,” says fifth-year tackle Tiger Shanks.

Mostly because the bones were reset properly.

Odom’s steady career ascent hit a security bollard in 2019, when his alma mater fired him after three years as head coach. He still hates what happened at Missouri. There are scars, he admits. But he also concedes the people who told him it could be a blessing were right. He became the defensive coordinator at Arkansas and, for four years, immersed himself in a structure and system that traced back to Nick Saban’s Alabama monolith, brought to Georgia by Kirby Smart and then brought from Georgia to Arkansas by Sam Pittman.

Odom tried to do it all at Missouri. Defensive boss. Marketing coordinator. Recruiting chief. And so on. When he couldn’t do enough, he tried harder. He recognized his folly while at Arkansas. He’s still enough of a maniac to get stuck in traffic on Tropicana Avenue at 4:45 a.m., on the drive into work. But once he gets there, Odom says, the job has slowed down. “I don’t know if there’s enough hours in the day – for me, some guys can do it – to do it the right way,” he says. “So it’s been really good to hire a great staff and understand and see it a little bit better.”

The Rebels are unapologetic copycat strivers, at least in terms of approach and structure. “It is an SEC blueprint,” Odom says. For one, the staff expects to compete for talent at Bishop Gorman, a top-10 national program 20 minutes from campus – not to shrug and cede recruits to Power 4 schools. “Then you’re a loser, because you’re taking a back seat,” Fertitta says. On the practice field, Odom applies lessons learned from that league. He didn’t totally understand why sometimes players were spread across two fields at Arkansas practices, so he discussed it with Smart and Pittman. It amounted to coaching cataract surgery: Split into four offense versus defense groups, and everyone gets the same reps. Everyone develops.

And there’s UNLV, for a few periods every day anyway, with basically no one standing around.

“My guess is, if you called Kirby Smart today, this practice plan would be almost identical to what they do,” Odom says. “And that’s by design.”

UNLV’s new way of doing things has carried water to a parched roster. “Seeing where this program came from when I first got here to where it is now, I feel like he’s just almost flipped it upside down,” all-purpose player Jacob De Jesus says. “Some of the players that are not here anymore would complain about the new way Coach Odom is doing things. And they ended up getting out of here real quick.”

To wit: Wednesdays and Saturdays were scheduled off-days during the offseason. Showing up for stretching and player-led walkthroughs was optional. The Rebels – unofficially, of course – had 100 percent attendance on off-days last summer. “When you show up to a college program on Saturday and it looks like a Tuesday practice?” says defensive end Antonio Doyle Jr., a transfer who previously played at Texas A&M and for Deion Sanders at Jackson State. “That explains everything you need to know.” Mandatory meetings begin in the Fertitta Football Complex during game weeks at 6:55 a.m. At 5 a.m. most days there are Rebels on site, for treatment or stretching or film work.

“That’s what winning is – relentless,” linebacker Jackson Woodard says. “It never sleeps.”

And yet it’s taken a football program in this city so long to wake up.

There may not be a ton of space between what UNLV tries to do and what power conference programs do. But there is massive space between UNLV and what defines big-time, power-conference football. Filling in the blanks is the animating dynamic of Odom’s tenure. It is the job.

“If you’re in this industry, your eyes are always open,” Erick Harper says, sitting at the end of a conference table, at the end of a much longer week.

The UNLV athletic director guesses he has slept three hours a night since his phone began buzzing the previous weekend. He was in Texas for the 40th anniversary of his state champion high school football team, and college sports realignment had another good laugh at sentimentality. Because the Pac-12 still needed more teams. “I probably spent more time on the phone than I did where I was at,” says Harper, who knows even a reunion can’t compete with discussing terms of separation.

Over the next few days, UNLV goes there and back to stay right where it is.

A Thursday morning conference call of school officials ratifies a decision made late Wednesday night: UNLV says thanks-but-no thanks to the Pac-12 and recommits to the Mountain West. The Mountain West effectively gives UNLV a signing bonus to do so, a sum estimated to be between $10 million and $14 million, plus another $1.5 to $1.8 million annually on top of UNLV’s share of established revenue streams. Just another few days in the deep end, looking for the best ladder.

It’s this life choosing UNLV, and UNLV choosing this life, all at once. To be a department with saucer-sized eyes for national football relevance, in 2024, is to seek the best and most profitable conference affiliation. At all times. Ambition costs.

UNLV practices feature people on the field whose jobs you’re not quite sure of, just by looking. But not nearly as many as there are at SEC or Big Ten schools. Odom plainly states that he wants the best recruiting department among Group of 5 schools. It’s currently a staff of two. “I don’t necessarily know that, always, more is better,” he says. “But there’s some things that we’re still trying to catch up to in support-staff areas. And those will happen.” The easiest way to make it happen is by hiring more people, which makes a massive direct deposit from the Mountain West in 2025 look pretty enticing.

So the school from Vegas places its bets, with no expectation the wheel stops spinning. “Obviously, there’s going to be a camera on us pretty consistently,” Harper says. “And this helps us achieve (national relevance) by solidifying who we are and what we want, as an institution. And that’s to be at the highest level. And that’s an autonomous conference. Whether we get there or not, who knows? But we’re going to put our best foot forward and try to get there.”

They will do so down one quarterback, who stacks a calamity on top of a dilemma when he says someone promised him $100,000 and leaves.

Sluka, a transfer from FCS Holy Cross, claims UNLV failed to follow through on NIL payments it said it would make during the recruiting process. He received $3,000 in “relocation” funds after enrolling and completing a charity appearance – this much everyone confirms – and that is it. As a result, Sluka’s UNLV career ends with 21 completed passes in three games. “We were never contacted by football, that they had an agreement with this kid,” says longtime donor Bill Paulos, who is helping spearhead UNLV’s nascent NIL operation. “If there is a monetary agreement, it comes directly to me. So if there’s a kid that’s getting $100,000, I’ll know about it.” Moreover, UNLV equates Sluka’s request, made via an agent, to a pay-for-play scenario. Which is illegal in Nevada. It’s a mess.

But maybe a necessary one.

Four decades of irrelevance means people are just noticing UNLV football again. It does not guarantee that they understand NIL payments have been permissible since July 2021, nor how elemental NIL is to a modern program luring and retaining top talent. Sluka isn’t even an outlier; last offseason, Rebels quarterback Jayden Maiava entered the transfer portal and left it with a reported NIL windfall from USC. “You have to educate the city on how important it is,” Odom says, hours before the Sluka news breaks. “Whether you like it or not, we have to be active in it.” He says NIL efforts were “zero” when he arrived at UNLV. Paulos describes the current football NIL budget as “miniscule.” But the root problem is bigger than someone finding $100,000 somewhere. It’s that people here might not even know that’s a thing.

This episode, Paulos believes, can be another neon sign in town. Because the starting quarterback left over money, and the phones started ringing. Circa CEO Derek Stevens even reportedly offered to foot the bill to keep Sluka, albeit too late to repair that particular bridge. “It’s an awareness,” Paulos says. “We’re not Corvallis. We’re not Albuquerque. We’re Las Vegas. There’s a billion things to do here. The competition is heavy. To get through the messaging is very, very difficult. But we’re getting our footing on getting the messaging out there.”

Hours after “Golddigger” plays during one of the Rebels’ final practice periods, after huddling his team and reminding them that success rests only on the people in that circle, Barry Odom briskly walks into PKWY Tavern far west of campus for his weekly radio show. To goose the attendance numbers, he’d promised to buy anyone wearing UNLV gear one Miller Lite. By the looks of it, many on hand order something stronger.

Odom flashes a thumbs-up and shakes hands on his way to the dais. The show goes live and he acknowledges a “roster change” at quarterback and that’s that.

He says he feels like his team is on the path to playing its best football on Saturday against Fresno State. As usual with these things, the hour is lacquered in spin and optimism.

It’s something that goes as expected, anyway.

UNLV quarterback Hajj-Malik Williams scores against Fresno State during a Mountain West Conference game Saturday at Allegiant Stadium. (Jeff Speer / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)

On Friday night, they meet at Born and Raised, a 24-hour bar about 10 miles southwest of The Strip. On Saturday morning, they reconnect in Lot G at Allegiant Stadium for a tailgate, catered by their alma mater. And at the first media timeout of the Fresno State game, the 1994 UNLV football team leaves its reserved suite and heads down to field level, to continue to remember and be remembered.

They smile. They hug. They pose with a bowl trophy. Some of them introduce their kids to their old pals. Everyone sports a gray commemorative T-shirt … except for Mark “The Terminator” Byers. For this occasion, the man who recorded 20.5 sacks that year and later went into competitive bodybuilding sports a black No. 48 jersey. TERMINATOR is the name plate.

Between quarters, the old Rebels line up in the south end zone. A video plays. And UNLV honors its most recent conference champion — a team that won the Big West and the Las Vegas Bowl three decades ago. A team that finished … 7-5.

Great to have members of our 1994 UNLV Football team back in Allegiant stadium

🔴 Big West Champions

🔴 Las Vegas Bowl Champions pic.twitter.com/KyjvBAyjc5— UNLV Football (@unlvfootball) September 28, 2024

That is how hard it has been to do something worth memorializing here. It’s what qualifies as good old days. But by the end of this day, a better kind of history remains dead ahead.

During starting lineup introductions, the new man under center receives the biggest ovation, and it’s not close. Hajj-Malik Williams then runs for a touchdown and throws for three more. He’s a comet in broad daylight. He leaves the field to chants of “That’s our quarterback!” from fans near the tunnel. There are also four interceptions, a blocked punt returned for a touchdown, a kickoff returned for another, and, all told, a 59-14 erasure of Fresno State for the program’s best start since before it was a Division I program, to cap its most tumultuous week in forever.

HAJJ TO RICKY TO PUT US UP BY 21

📺: FS1 pic.twitter.com/WkRj0ExnOE

— UNLV Football (@unlvfootball) September 28, 2024

A crowd of 24,638 doesn’t set records – there were two better-attended home games late in 2023 – but it fills the lower bowl, and enough stick around to chant “We want 60” as the clock winds down. “There was never any buzz around the city about UNLV,” Fertitta says, “and now … that’s all everybody’s talking about, are the Rebels. And the one thing that sticks with me is everybody always says, ‘Man, it’s about time.’”

Afterward, with his hat pulled low as Saturday evening creeps up on the desert, Odom talks about turning the page very, very quickly before turning to a prepared statement about the Sluka ordeal. UNLV’s coach laments “very strong opinions about the events of last week without full knowledge of the facts,” among other things, and that’s the end of his comments on the matter. It’s a predictable open-and-shut move.

After all, he is the coach who sits in his office a few days earlier and notes that a 12-team playoff means hope … but no margin for error. And up next is Syracuse. Then road games at Utah State and Oregon State. Then a possible playoff-eliminator showdown with No. 21 Boise State. “And is that pressure?” Odom says. “Hell yes, it’s pressure. But that’s exactly what we signed up for. I would much rather have it that way than no shot at all.”

A week-long immersion in modern college football chaos, and this much remains true at UNLV: The door’s still open.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb, Kelsea Peterson / The Athletic; photos: Jeff Speer / Getty Images)