Wet your hat with water, avoid certain medications and other smart tips to prevent deadly heatstroke on holiday, as revealed by PROFESSOR ROB GALLOWAY

One of the great pleasures of summer is taking a long walk or participating in outdoor activities without having to wrap up warmly against the elements.

But with temperatures rising later this month and the holidays just around the corner, it’s a good time to remind ourselves of the real dangers of heatstroke.

It is not just a matter of feeling warm, it is a vastly underestimated condition that can quickly cause irreversible damage to our organs and can be fatal.

Last year’s heat wave in Europe, which saw temperatures rise above 48 degrees, is estimated to have killed 60,000 people.

Heat stroke is an underestimated condition that can quickly cause irreversible damage to our organs and can be fatal.

And of course the issue has recently been raised again following the tragic death of my esteemed colleague, Dr Michael Mosley, who was found unconscious on the Greek island of Symi. Although the exact cause is unknown, the searing heat appears to have played a part.

And temperatures don’t have to be particularly high to pose a health risk — the risks increase as temperatures rise above 25 degrees Celsius, especially if it’s humid and warm (more on that later). These risks begin to increase within minutes of exposure to high temperatures.

Some groups are particularly vulnerable, such as the elderly, overweight people or people with an infection. In these situations, the body cannot regulate its temperature properly.

But the biggest risk factor is if you are not used to the heat. For example, if you suddenly go from dark, damp England to two weeks in a sunny paradise, you are much more at risk than the locals who have adapted to that weather.

But as someone who has treated cases of life-threatening heat stroke, I can tell you that there are ways to prevent it.

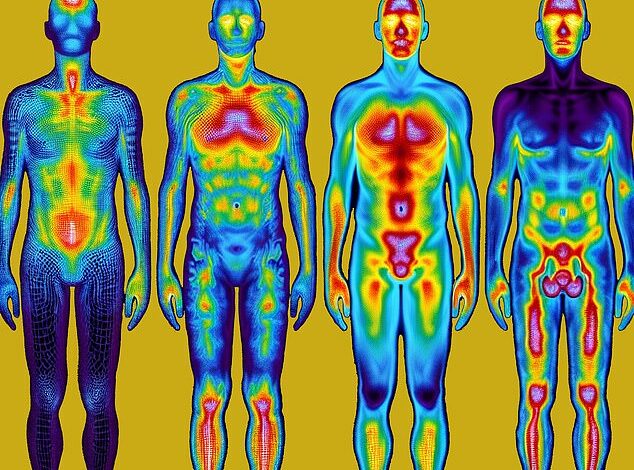

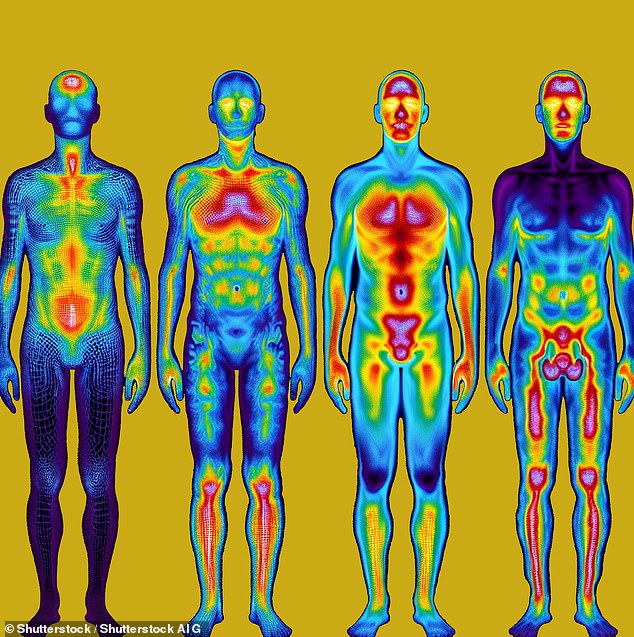

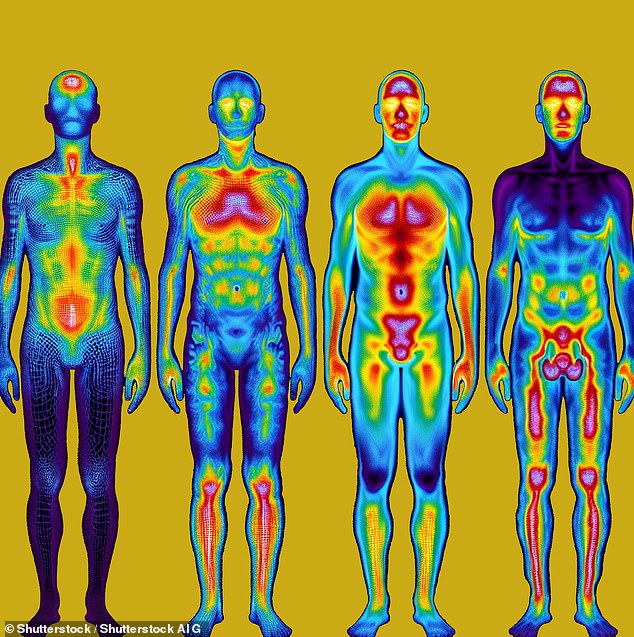

First, it’s helpful to understand how heat can be so quickly and devastating to the human body.

Our bodies are designed to function at a temperature of about 37 degrees Celsius. The enzymes and proteins that are crucial to processes such as sending nerve signals throughout the body begin to break down as the temperature rises.

The searing heat is thought to have played a role in the death of Mail columnist Dr Michael Mosley, who fell asleep on the Greek island of Symi last month

This can have serious consequences: cells die, toxins are released and organs literally shut down.

To prevent this, our body has very sophisticated mechanisms to sense and regulate body temperature as close to 37 degrees Celsius as possible. This is why we sweat when it is hot outside, for example, because the sweat evaporating from the skin has a cooling effect on the body.

But under certain circumstances, the mechanisms that regulate our body temperature are not so effective.

For example, in hot and humid conditions, the air is already full of moisture, which prevents sweat from evaporating efficiently. And if sweat can’t evaporate, it can’t cool the body, causing a dangerous rise in body temperature.

Intense exercise also creates its own body heat, so much so that the body cannot sweat enough to cool itself. If the exercise is long and intense, such as marathon running, you can get heat stroke in normal temperatures.

Confusion is often the first sign of heatstroke, because brain cells are most sensitive to temperature changes.

Other symptoms of heat stroke include dizziness, nausea, pounding headache, hot, red, and dry or moist skin, rapid pulse, and fainting. These are all red flags to watch out for.

As cell damage progresses, all of our organs can slowly fail within minutes. But with effective treatment, this can be stopped and reversed.

The heat damage occurs through a number of mechanisms. We are slowly unraveling the science behind these mechanisms so that we can develop better treatments.

Often the first sign of heat stroke is confusion, because brain cells are most sensitive to temperature changes

First, more blood is pumped to the skin to promote sweating, which reduces blood flow to the major organs. This can lead to organ failure.

Proteins in the muscles are broken down and enter the blood, damaging the kidneys.

Lack of fluid also plays a role: you can sweat as much as 1.5 liters of fluid per hour, which causes dehydration and a decrease in blood volume. This makes it harder to maintain proper blood pressure.

All of this means that the heart has to pump faster and harder to push blood to the skin — and we know that can be taxing on the heart. This was illustrated last month by a study in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine.

Canadian researchers studied 60 adults and found that for every 1.5 degrees Celsius increase in body temperature, blood flow to the heart doubled in younger, healthier patients.

In people with heart disease, not only was there a reduced increase in blood flow, but there was also ischemic damage to the heart, which is a precursor to a heart attack.

Meanwhile, research in last year’s European Journal of Applied Physiology showed that damage to the gut occurs as body temperature rises, and that older people suffer more damage than younger people.

This group is thought to be particularly susceptible to damage to the gut, which allows bacteria to enter the bloodstream, causing sepsis, a life-threatening response to infection.

Studies like these have led many of us in the emergency room to start giving intravenous antibiotics to people seriously ill with heat stroke.

As an ER physician, I have indeed seen patients tragically die because treatment was not delivered quickly enough.

Others have suffered serious injuries and have had to stay in hospital for weeks. People who do recover well physically often suffer from reduced cognitive functions for months after their heat injury.

And when it comes to effective treatments, the UK is leading the way thanks to research by military doctors into the effects of heat on military personnel and marathon runners. Despite being fit, they are at risk of heatstroke as a result of extreme exertion in high temperatures.

A life-saving innovation, originally developed for the Royal Marines, is the portable ‘ice-cold water bag’.

Developed by Dr. Ross Hemingway of the Marine Corps Commando Training Center, this is used to wrap the body of a person suffering from heatstroke and immerse them in ice-cold water. It can be so effective that they don’t need further treatment.

Vacationers should consider soaking their hats in cold water before heading out

This is because we now understand how important it is to cool the body as quickly as possible, before heat damage occurs.

It has been successfully used to treat 75 members of the armed forces suffering from heat stroke, some of whom would undoubtedly have died otherwise.

Last year I saw its effectiveness first-hand when it played a role in saving the life of a civilian for the first time: a runner in the Brighton Marathon, where I was medical director.

Even if you don’t run a marathon or train like a Marine, there are lessons we can all learn to protect ourselves from heatstroke.

These measures apply both at home and abroad, where the threat of extreme temperatures is easily underestimated.

Firstly, if you are planning a holiday in warm conditions, it is crucial to acclimatise to the heat. Spending time in a sauna before a holiday can therefore be an incredibly effective preventative strategy.

And if you do go, stay out of the sun, as temperatures can reach 30 degrees Celsius. Go out in the evening, as it is likely to be cooler.

In addition to sunscreen and a hat, wear light-colored clothing made of cooling fabrics (cotton is best). These fabrics allow heat radiation and sweat to pass through.

Heat stroke goes hand in hand with dehydration, so we need to drink much more than normal. Make sure you are never thirsty, that your urine is pale and clear — and avoid coffee and alcohol, as both are diuretics.

Do more to stay cool: Tour de France cyclists wear an ice jacket before they ride. You can also do this by soaking your hat in cold water before you set off.

Heat stroke goes hand in hand with dehydration, so make sure you never go thirsty

If possible, you should also avoid anti-inflammatory drugs such as Voltarol and ibuprofen. As I have warned before on these pages, they can impair kidney function and damage the gut, making you more likely to suffer from heat stroke.

If you notice yourself starting to feel unwell or if you notice someone becoming confused in the heat, simple first aid will help: get out of the sun, drink cold water and cool down.

If you don’t feel better, take a cold shower — you should feel better within five to ten minutes. If that’s not practical, drape damp towels over yourself.

If the situation worsens, the treatment is immersion in cold water. You will need assistance for this. Seek help as soon as possible.

DO THIS…

Take up gardening: research from Anglia Ruskin University says it could reduce your risk of depression.

A review of studies of physical activity as a mental health intervention found that the greatest benefits were achieved with light and moderate activities such as gardening, golfing and walking, rather than vigorous exercise.

“Moderate exercise improves mental health via biochemical responses, while vigorous exercise may worsen stress-related responses in some people,” the researchers said.