What makes Leon Marchand a superstar? He’s smaller, lighter and incredibly underwater

Leon Marchand is an enigma.

Over the past eight days, he has delivered one of the best Olympic pool performances, including an unprecedented double gold medal in the 200m breaststroke and 200m butterfly.

Only one athlete had ever reached the final in both strokes over any distance. That was Mary Sears in 1956, when the American won bronze in the 100m butterfly and placed seventh in the 200m breaststroke.

Marchand, who also won the 200m and 400m individual medley, took home four individual gold medals in four Olympic-record times. Those performances are not unusual, even by elite standards. The 22-year-old is the fourth swimmer and first French Olympian to win four individual gold medals in a single Games — after the United States’ Mark Spitz (1972), East Germany’s Kristin Otto (1988) and the U.S.’s Michael Phelps (in 2004 and 2008).

The comparisons between Marchand and Phelps write themselves. Marchand’s coach at Arizona State University, Bob Bowman, previously coached Phelps. In early 2023, Bowman said, “Leon reminds me of Michael in 2003.” Bowman was talking about what Leon swam, not how he swam, and praised his ability to post fast race times despite high training volumes.

Physically, Marchand looks more like Spitz than Phelps. Phelps is six centimeters (2.4 inches) taller (193 cm versus 187 cm) and raced 7 kilograms heavier (84 kg versus 77 kg) than the Frenchman. Marchand can’t match the American’s 79-inch wingspan. Part of Marchand’s appeal is how he bucks the trend of Olympic swimmers getting bigger and longer.

GO DEEPER

Meet Léon Marchand, the ‘French Michael Phelps’ who is ready to dominate the Olympic Games in his home country

A paper from 2020 collected nine studies that analyzed Olympic swimmers between 1968 and 2016. It was “advantageous for swimmers to be older, taller, and heavier.” From Mexico City in 1968 to Rio de Janeiro in 2016, the world-class 200-meter swimmers (Marchand’s favored distance) changed dramatically: on average, they grew 8.6 cm (3.4 in) taller and 7.9 kg (17.5 lb) heavier.

The authors of that paper spoke of the “natural selection” of athletes into events based on their body type and stroke aptitude. Freestyle swimmers were the largest, all about power and big, long limbs. Butterfly swimmers were the smallest, with backstroke and breaststroke swimmers in the middle. Imagine a Venn diagram with Phelps in the overlapping free/fly/back rings, and Marchand in the breaststroke/fly/back.

Francisco Cuenca-Fernandez, a graduate of the University of Granada’s Hydrology Laboratory and professor specializing in varietal analysis, explains why Marchand’s atypical size is an advantage.

“Swimmers tend to be large because a large body size is associated with a long lever arm, which is very advantageous because it allows propulsive surfaces, such as the hands, to remain underwater longer and exert force.”

But that size is a double-edged sword. “There’s a downside to it,” says Cuenca-Fernandez. “A big body can also generate a lot more drag. In Marchand’s case, his events were always middle distances — the 200m and 400m — which suggests that a big, muscular body would have cost a lot of energy.

“We haven’t seen him compete individually in the 100m butterfly or 100m breaststroke and he hasn’t really excelled in his freestyle relay performances either. He’s a swimmer who doesn’t stand out because of his size or muscle mass, but this makes him incredibly efficient.”

Efficiency.

It was the difference between Marchand and Hungary’s Kristof Milak in the 200m butterfly final, where sprint specialist Milak led at 150m but Marchand’s speed at the back left him closing in. Cuenca-Fernandez uses that word repeatedly to describe Marchand.

“He moves easily and that saves a lot of energy. That’s where he makes the difference,” says Cuenca-Fernandez, who credits Marchand’s efficiency to a combination of his training under Bowman and innate physiology, a virtue instilled in former Olympian parents.

It’s how Marchand beats his opponents in the medley, with his strongest strokes first (butterfly) and third (breaststroke) and his weakest second (backstroke) and last (freestyle). “This efficiency is greatest in butterfly and breaststroke, strokes where it’s hard to maintain cadence because the body is constantly accelerating and decelerating, which leads to rapid fatigue,” Cuenca-Fernandez says.

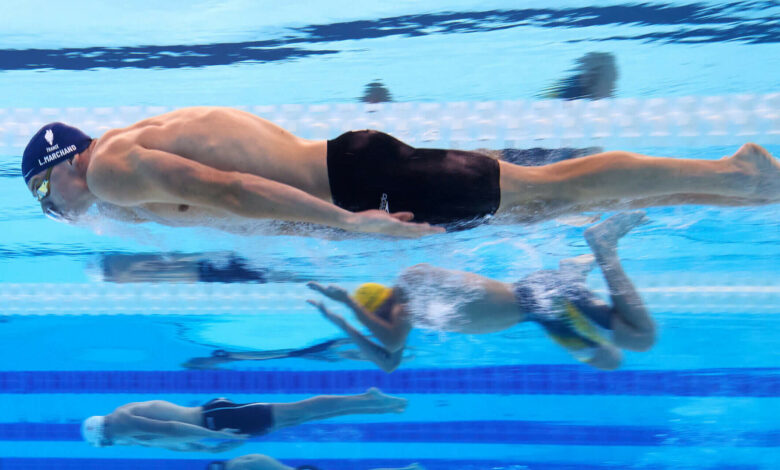

Marchand in the semi-finals of the 200m butterfly in Paris (Sebastien Bozon/AFP via Getty Images)

Breaststroke is also leg-dominant, so guys with large torsos and wingspans don’t benefit as much. “It’s clear that his race strategy is based on being strong in those two strokes,” says Cuenca-Fernandez, who explains that Marchand’s natural strengths work tactically.

“I start strong in butterfly, with powerful undulations (wave-like movements with the body). In backstroke, I hold the position, because I can breathe much easier than in the other strokes. In breaststroke, I take advantage of my underwater efficiency, both in the underwater phase after the push off the wall and in the glide phase, and push hard again. In freestyle, I give everything I have left, less tired than others.”

Marchand’s efficiency—combined with elite fitness—is what makes him so good underwater. He glides and kicks like no other. In the 200m breaststroke final, he had a 1.8m lead over runner-up Zac Stubblety-Cook going into the final turn, but stayed underwater so long that he surfaced after his nearest opponent was even further ahead.

In the 400m individual medley, Marchand spent 100m underwater, about a fifth more than his opponents — Phelps spent 77m underwater during the same race in Beijing in 2008. Marchand spent 14.77m of the allowed 15m underwater on the final turn when he set the 400m individual medley world record last year in Japan.

“That incredible underwater swimming is a hallmark of swimmers trained by Bowman,” Cuenca-Fernandez says. Even Phelps is astounded by Marchand’s glides. Bowman once said they “weren’t an issue, they’ve always been excellent.” Marchand is built to swim underwater, with what Bowman calls a torpedo-like body and “no hips.”

Cuenca-Fernandez says: “The depth of his underwater undulation is striking – this trajectory to the bottom of the pool after the take-off of each turn.

“This provides an advantage — as long as you have the lungs for it — the reduction of wave resistance. When a group of swimmers reaches the wall at full speed to turn, a mass of water is dragged along and eventually hits the wall.

“If your turn is too close to the surface and you’re a little bit ahead of your competitors, that body of water will hit you just as you’re doing a somersault or taking off and slow you down. However, if you go to the bottom of the pool after your turn, that body of water will go over you and you can avoid it.”

It depends on the athlete, particularly his or her body type and strength when swimming on the surface, but underwater swimming is generally faster because turbulence and drag are reduced (although this is not true for freestyle, where surface swimming is faster than backstroke, butterfly and breaststroke).

In one of the studies of Cuenca-FernandezBy assessing the performance variability of swimmers who were completing championship rounds, they found that the push-off in the first five meters from the turns was the only consistent variable. Things like stroke volume, start, and underwater kick all changed.

“Those who reached the final were always faster, they had better underwater gliding skills and they offered less drag,” he says. “The speed of that push was always the same for a given swimmer. I am sure that if we analyse Marchand thoroughly, he would be one of the fastest at that moment, because he is a swimmer who generates very little drag.”

Marchand’s style is something psychologists call the underdog effect — when athletes succeed despite disadvantages. Often these are sociocultural, economic, or geographic disadvantages, none of which apply to Marchand, but he is a fourth quartile baby (May) and physically late maturing.

Santiago Veiga Fernandez, a former head coach of the Spanish national junior swimming team who holds a doctorate in swimming race analysis, explains. Marchand, he says, benefited from “great development work” from his French home coach, Nicolas Castel of the Toulouse Dolphins club. During his junior years — from 16 to 18 — Marchand developed the basic skills that allowed him to excel underwater.

“When he competed in the European or World Junior Championships, Marchand did not dominate. He won bronze in a number of events (European bronze in the 200m breaststroke and 400m medley; world bronze in the 400m medley). His body was not yet fully developed, but he already showed a great level of skill in gliding and underwater swimming.”

He had to be a good glider underwater—he didn’t have any freestyle power or speed anywhere near Phelps’. Marchand’s personal best in the 100m freestyle is almost four seconds slower, though he is a better freestyler than Phelps was in breaststroke (Marchand’s personal best in the 200m breaststroke is more than five seconds faster than Phelps’).

Scheduling is a big reason why the breaststroke/butterfly double is unique, as they take place in the same evening session. This requires specialization (World Aquatics even had to adjust its Olympic schedule to accommodate Marchand).

Another reason, Veiga explains, is the differences in technique. “The kicking motions in butterfly and breaststroke are exactly opposite, and swimmers with a large range of motion in one stroke may not excel in the other.

“In breaststroke, you are only allowed to perform one underwater dolphin kick after jumping off the block or pushing off the wall, while butterfly swimmers are allowed to perform multiple underwater dolphin kicks.”

These steps require the feet to bend in different ways (because the arm movements are different). It may seem small, but at the highest level, details make a difference in performance.

Marchand in the butterfly (Quinn Rooney/Getty Images)

And in the breaststroke final, where the difference in technique was highlighted (Ian MacNicol/Getty Images)

Given his exponential improvement since Tokyo, it’s scary to think where Marchand might be in four years. Improve his freestyle and the world records will come crashing down. Veiga says the 200m breaststroke showed Marchand becoming a versatile racer, as he swam hard from the start to compensate for Stubblety-Cook’s fast last 50m rather than trying to win it late.

Ultimately, Marchand has put French swimming in a better position. They have not won gold in the pool at the last two Games and have won four medals between them in Tokyo and Rio de Janeiro, the same as Marchand won in Paris alone.

France’s golden boy has changed the face of swimming. There’s more than one way to win an Olympic gold medal. Or four…

(Top photo: Adam Pretty/Getty Images)