What’s in a name(change)? For Josh Hines-Allen, it was about roots and recognition

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — With a season of 17 1/2 sacks, a second Pro Bowl appearance and a new contract that made him the highest-paid outside linebacker in football, Josh Allen had become an undeniable name in the NFL. But not exactly in the way he wanted.

He was often referred to as “the other Josh Allen, the most famous of whom is the Buffalo Bills quarterback.

The Jacksonville Jaguars pass rusher and his wife Kaitlyn were watching highlights from this year’s Pro Bowl Games and listened to a commentator say, “Aidan Hutchinson and Josh… Allen?”

“It was almost like she didn’t know who I was,” he says.

She wasn’t alone. Kaitlyn wanted to know where her husband’s jerseys were being sold and discovered they were as hard to find as disinfectant wipes during the pandemic. The 27-year-old, five-year NFL veteran and father of three had been considering changing his name for years. Now his wife was pushing for it.

His four older sisters have a different surname, Hines-Allen, which includes their mother Kim’s maiden name. When Josh and twin brother Isaiah were born, their father, Robert, wanted the boys to be Allens. Kim and Robert divorced when Josh was a baby, and his father wasn’t around much, so the boys were raised and shaped by Hineses. In his New Jersey neighborhood, Josh was known as “Little Hines.”

So, in the off-season, Josh hired a marketing agent and a lawyer. He stood in line at the courthouse that serves Duval County. There were stacks of forms to fill out. He had to verify the addresses of every place he’d lived from birth to the present. He had to identify all of his family members, their residences and ages. Changes had to be made to his driver’s license, Social Security information, and tax returns.

In July, his marketing team released a video announcing the changeand a new teal nameplate was placed above his locker. That’s when Josh Hines-Allen became who he was meant to be.

A former professional basketball player, Uncle Greg “Dunkin’” Hines (left) is an important figure in Josh Hines-Allen’s life. (Courtesy of Greg Hines)

The new name is about how he hopes to elevate. And it’s about what grounds him.

Morris Hines was a powerhouse. Morris was considered a basketball legend on the streets of their New Jersey neighborhood. He founded a basketball team at New Hope Baptist Church in Newark and instilled a love of sports in his descendants, including his grandson Josh. Morris taught Josh how to shadowbox. He used to say, “Cut ’em deep and make ’em bleed.” Josh has it tattooed on his inner forearm. Josh learned to tie a tie from Morris. In fact, he tied teammates’ ties and taught them how Morris did it.

“He’s one of the main reasons why I am the way I am mentally and competitively,” Josh says.

Morris’s oldest son, Greg, was more of a father figure to Josh than an uncle. He was also a legendary basketball player and an example of how sports can change a life. “Dunkin’ Hines” was a dominant big man at Hampton University and an inaugural member of the Hampton Athletics Hall of Fame. A fifth-round pick of the Golden State Warriors, Hines never made it to the NBA but played professionally for 12 years.

At 12, Josh was the only male in the house, Isaiah lived in Alabama with relatives. His sisters drove him crazy by “mothering” him.

“It was just sad,” he says. “I was already going to school, and then they made me go home to ‘class’ with them as my teachers. It was just because they wanted to. We had math, science, and recess.”

Desperate to get out of his house, Josh moved in with Dunkin’ Hines, who took Josh and his dirty clothes to the laundromat and taught him how to wash, dry and fold them. Josh learned to count the coins they had saved in a jar and change them into cash at a change machine. Hines made him feed and clean up after Blazer, his white boxer.

Josh and Hines imitated WWE wrestlers Josh saw on “SmackDown” and “Raw” and tried to get the other to tap out. At 6-foot-9, 280 pounds, Hines had a significant advantage, teaching Josh to use leverage and his fast, strong hands.

“Those nights were so amazing,” says Josh.

Hines tutored Josh on the basketball court, where he remembers his cousin as an average ball handler, but strong and very athletic for his size, with a knack for rebounding, loose balls and defense. When Josh became frustrated with basketball, Hines signed him up for football for the first time.

When Josh moved here, Hines was a bachelor enjoying the privileges of freedom and fame. He felt Josh needed some religion, so they walked to Rising Mount Zion Baptist Church in Montclair every Sunday morning, where they experienced an amazing grace together.

“I had no structure, no responsibilities in my life,” Hines says. “That grounding, putting God at the center of our lives, helped both of us.”

Josh also looked up to Keith Hines, Greg’s brother and Kim’s twin. Cousins called Keith “The General” because he didn’t mess around. Basketball was also in his blood, as The General once scored 59 points in a high school game and went on to play at Montclair State before becoming a high school coach.

It wasn’t just the men in the family who paved the way for Josh.

Josh’s appreciation for the pageantry of the game grew as he sat in the stands at Montclair High, watching his sister Torri, who would later play for Virginia Tech and Towson. He would get chills every time the lights dimmed and Torri and her teammates burst through a poster into blinding strobe lights.

“I thought it was super cool and it made me fall in love with that part of the sport,” he says.

Sister Kyra played basketball at Cheyney University the way Josh plays football. “You didn’t want to mess with her, you know what I mean?” he says. “She was the smallest of my sisters, but the strongest, and I loved the way she played.”

Myisha, a year older than Josh, played against sixth-graders when she was in fourth grade. In high school, she was a McDonald’s All-American. At Louisville, she was first-team All-ACC three times and played on a Final Four team. She won a WNBA championship with the Washington Mystics in 2019 and was named second-team all-league the following year.

Josh’s entire athletic experience has revolved around trying to keep up with Myisha, who he could never compete with on the basketball court. A year after she was picked 19th overall in the WNBA draft, he wanted to be drafted higher, which he did (seventh). Now he’s determined to win a championship like she did — and to outdo her by being named first-team all-league.

Myisha and Josh didn’t have a good bond as children, but their relationship has grown as professional athletes.

“I try to motivate her, guide her on the right path, keep her mind straight,” Josh says. “She does the same for me.”

Myisha Hines-Allen (left) won a WNBA championship in 2019 as a member of the Washington Mystics. (Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

Shortly before the Jaguars play the Bills in September, Josh plans to offer fans the opportunity to trade in old “Allen” jerseys for new “Hines-Allen” jerseys at a discounted price. It’s a good week to do it, since the game is on a Monday night and the players have some extra time — plus his opponent is the other Josh Allen.

They never swapped sweaters. They never exchanged phone numbers or even pleasantries.

“I don’t think he likes me,” Hines-Allen says. “After the first time we played them, he walked right past me and didn’t say anything. The second time, I didn’t care.”

If the quarterback is bitter, he has a reason to be. Hines-Allen has kept him from winning both games they’ve played against each other. In the first game, a 9-6 victory in 2021, the Jaguars linebacker sacked and intercepted the Bills quarterback and recovered his fumble. And the Jaguars won the second “Josh Allen Bowl” by a score of 25-20.

For Hines-Allen, those games weren’t just any games.

“It was kind of a respect thing — you have to earn respect,” said Hines-Allen, who vowed never to lose to the Bills QB. “I feel like I did, but if we didn’t win, it would have been like, ‘Oh, and you lose to him?’ It definitely brought out something extra in me, because my name is my name. I respect everybody and want the same to be given to me.”

If Hines-Allen breaks the NFL sack record of 22 1/2 — as he plans to do — there will be more respect. He charges the passer with extreme momentum and unpredictable winds, making him as easy to stop as a tornado. He had 17 sacks in 13 games at Kentucky and 22 1/2 in 12 games at Montclair High. Five and a half more than he got in 2023 doesn’t seem unreasonable.

He believes his record-setting pursuit will be spurred by less dropping and more rushing in the scheme being implemented by new Jaguars defensive coordinator Ryan Nielsen. Head coach Doug Pederson sees Hines-Allen “pushing that 20-plus sack range” with more support from his team.

“He’s one of those guys that shows up early and stays late,” said Pederson, who recently became Hines-Allen’s neighbor when the linebacker bought a house near his coach. “He has the determination to be great.”

He hired a chef to prepare his meals and sleeps about five hours a night in a hyperbaric chamber. He takes the machine to away games, along with a specialist to administer intravenous fluids and his personal physical therapist.

During his pre-match routine, he makes himself the only person in a crowd of thousands by wearing noise-cancelling headphones and listening only to silence. He’s normally sociable, with an easy smile and hugs all around him. But there’s a dark side.

“I’m mad,” he says. “I had a great season last year, but all I got was a Pro Bowl. I’m mad because you guys think I should be happy. I’m mad because I wasn’t All-Pro. I’m mad because I wasn’t nominated for defensive player of the year. I’m mad because my team didn’t make the playoffs.”

So now there are quarterbacks to pound, honors to be earned, triumphs to be had, a legacy to uphold and another to be created. And opponents who have studied the 2023 tape will realize that the linebacker across from them is not the same one who wore No. 41 last year.

This is Josh Hines-Allen.

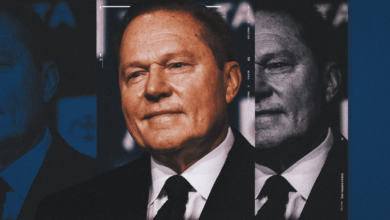

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletics; photo: Cooper Neill / Getty Images)