Women’s basketball is not having a moment. This is our new reality

I was in seventh grade and the first time sportswriting gave me a visceral feeling. UConn finished a 39-0 season and won its third national title in eight years, and I was anxiously awaiting the delivery from Sports Illustrated.

When it arrived, Juan Dixon of Maryland graced the cover, but the top of the April 8, 2002 magazine read: “UConn’s AMAZING WOMEN, Pg. 44.”

I immediately skimmed past “Faces in the Crowd,” where you could reliably see female athletes in the 2002 magazine, and skimmed the section that chronicled the lives of UConn’s tight-knit seniors: Sue Bird, Swin Cash, Asjha Jones and Tamika Williams. How they lived together off campus. Cooking weekly family dinners. Fought over card games and bet on who would cry first on senior night. …I ate it.

These details stuck with me years later, because as a women’s college basketball fan in the 1990s and 2000s, I didn’t have much to say about the most exciting teams and players. You rarely forgot anything. Facts just existed in your brain (sometimes for the next twenty years).

After re-reading the UConn story, I went to the back page to check out the column I always read: “Life of Reilly.”

The headline? “Not in touch with my feminine side.”

“Do you think it’s hard to coach in the Final Four? You think it’s hard to deal with 280-pound seniors, freshmen with agents, athletic directors with pockets full of pink slips? columnist Rick Reilly began. “Please. Try coaching seventh grade girls. After 11 years of working with boys, I helped coach my daughter Rae’s high school basketball team this winter. I learned something about seventh grade girls: They are usually in the bathroom.

Those few pages about the intense, elite women of UConn were sandwiched by a three-word headline on the cover and 800 words better suited for bad movies or lazy literature on the back page. It was disappointing and frustrating. Worst of all, it was expected even for my seventh-grade self.

For much of sports history, female athletes (and their fans) have had to accept the highs with the lows and move on, realizing that too often the lows were intentional – a lack of investment, institutional support or attention. Later, those lows were artificial reasons to maintain and hold back the sport. It’s the women’s sport of Catch-22.

The “Caitlin Clark effect” permeated the WNBA this summer, with teams from across the league – not just the Fever – drawing record attendances and huge TV ratings. As the women’s college season began this week, interest continues even without the stars who took women’s college to a new level.

GO DEEPER

Paige Bueckers vs. JuJu Watkins: How UConn and USC stars will keep women’s basketball in the spotlight

Defending champion South Carolina sold its season ticket packages for the first time in program history. UConn sold out its season tickets for the first time since 2004. LSU and Iowa, without Angel Reese and Clark, respectively, sold out. Texas, Notre Dame and Tennessee are also reporting huge increases.

Five months before the national title game, Final Four tickets are sold out and the resale market is buzzing. Nosebleeds for the national championship game cost almost $200, while a courtside seat costs almost $3,000.

For the first time since 2004-05, our Gampel Pavilion season tickets are SOLD OUT!

There are still a limited number of season tickets available for XL Center matches ➡️ pic.twitter.com/QGyhYGh81F

— UConn Women’s Basketball (@UConnWBB) October 2, 2024

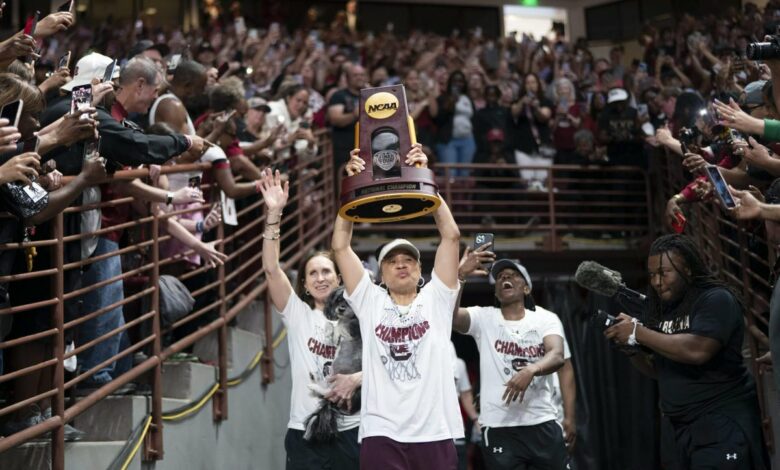

No one in women’s ring has won like Dawn Staley: Final Fours as a player, national titles as a coach, Olympic gold as a player, Olympic gold as a coach. Her South Carolina office is dripping with memorabilia. But despite all her special achievements, this particular moment in women’s basketball feels uniquely different for her. “It feels like we’re free to explore where this game can go,” she said. “There are no boundaries with us, and that’s why you see talent, you see coaching, you see fan support, you see viewers – you see all these things.”

Staley speaks often and openly about how the women’s game was deliberately held back by so many for so long. First, due to the exclusion of women in sports before Title IX. Then by the NCAA, which prioritized men’s college basketball. Also by television media partners, who refused to expose the game to as many people as possible (and then used that lack of audience as a reason not to air it on major networks), and by print media coverage, which refused to write about women’s sport (and then often claimed that no one read about it).

Then came last season. A year in which the women’s national title game drew nearly 4 million more viewers than the men’s title game, just three years after the Kaplan Report exposed the NCAA’s deliberate undervaluing of the game and allowing its media partners to underpay.

“This,” Staley said with a pause, gesturing with her hands to indicate everything from the past year. “I never thought this would happen at a time where I could be a part of it.”

Anyone who has played women’s basketball will share both the guarded optimism and excitement for this season. Will this finally be the turning point? Will the forces that held the game back step aside for good?

Tara VanDerveer has seen it all, including what she believes was the turning point. Twenty-two thousand people showed up for Iowa vs. Ohio State in 1985, her first season in Columbus. But it turned out to be an outlier. Throughout her career, which started with driving the team bus and doing laundry as an assistant coach and ended last season at Stanford with three title rings and 1,216 career victories, she has experienced those starts and stops, moments when a moment had could turn into momentum if it had investment, support and excitement.

“We had to build on that and not let it be a one-off,” VanDerveer said. “We keep our eye on the ball and let the game grow. There are more young girls playing. Great high school tournaments, enthusiasm for the college game. People are excited about the WNBA.”

VanDerveer says that’s what it feels like today.

Clark took the game to new heights last season. This year, USC’s JuJu Watkins, UConn’s Paige Bueckers and the Gamecocks — coming off a 39-game winning streak — are poised to continue the momentum. NIL has completely changed the way female basketball players are marketed (and empowered), bringing in new fans. The transfer portal opened up the movement of players and democratized the increasing equality of the game. Look around and you’ll see no fewer than ten teams that look capable of going to the Final Four. Gone are the days when a UConn or Tennessee could win so much that they were blamed as bad for the sport.

Less than a week into the season, we’ve already seen top-five teams pushed to the brink. The talented stars in women’s hoops? They draw. But equality, which has never been better, and the true belief that anything can happen on any given night? That’s compelling.

What we see is long overdue, and it still feels like it’s only just begun.

For decades, women’s college hoops deserved better than playing second fiddle to the NCAA court. It had to be untethered so that the moments could flow together into something bigger and better. It was worth more than three words on the front cover and a condescending column on the back page. It deserved full distribution. So please, decision makers and stakeholders, don’t screw this up.

There is a new generation of seventh graders watching.

(Photo by Dawn Staley: Sean Rayford/Getty Images)